THE gate is still there, swung open and resting against the wall at the bottom of the stairs. Roughly six foot by four of beige-coloured metal, it’s more like something you would see at a garden entrance rather than an indoor hallway.

“It’s not the nicest looking thing, I know, but...” says Irene Graham, voice tailing off as tears fill her eyes.

For over 20 years the gate has been there, its placement borne of necessity rather than design. Every evening, Irene and her husband Paddy shut it behind them when they head upstairs, whispering goodnight to their son Paul before turning in.

That’s who her tears are for. Paddy’s too.

Paul Graham was born with microcephaly, a condition where the head is smaller than normal. Severe learning difficulties meant he was never able to talk, yet Paul was the beating heart of their McQuillan Street home from the day and hour he arrived through the door.

A mischievous smile seemed to permanently adorn a face that never aged - especially when flicking between TV channels from underneath a blanket in the corner of the living room, leaving his poor parents searching frantically, and fruitlessly, for the remote.

Paddy and Irene haven’t seen that smile in nearly 13 years, other than in photographs in cabinets and on walls.

The gate, installed in case Paul should wander from his bedroom during the night, remains in place because they can’t bring themselves to have it removed.

Since June 14, 2006 their precious son hasn’t been there to say goodnight to. That Wednesday morning he left home and never came back.

During a 20-plus year career in the ring, amateur and pro, Paddy Graham took plenty of gut shots and suffered more than his fair share of disappointments and hard knocks.

Yet the more time that passes, the more distant the sound of the bell becomes, the more the realisation dawns. He thought he knew pain. He thought he had experienced it all.

He hadn’t a clue.

*******************

THE scrapbooks and cuttings are neatly laid out on the living room sofa. Paddy Graham, wearing a yellow t-shirt with the Clonard boxing club badge emblazoned on his chest, picks one up and begins to leaf through.

Every single page has a story to tell.

“That’s a big Romanian I fought at the European Championships,” he says, pointing at a picture of his younger self between the ropes with a man who looks, and quite possibly was, two weight divisions heavier.

“He was an absolute giant, I’d never seen the like of it. He hit me in the last round and I thought I was back in the Ulster Hall...”

Where were you?

“Rome!” he laughs, “it was bad enough fighting one of him but see when your eyes go and you’re having two or three of them coming at you... I remember him coming at me and thinking ‘just grab the one in the middle and hold on for dear life’.

“Thank God I grabbed the right one.”

The reason we have agreed to meet up today is for a general piece about his career. After all, Graham was once talked of as heir apparent to the great Johnny Caldwell – a spiteful puncher famed for his bloody 1962 battle with Belfast rival Freddie Gilroy.

But, despite all his achievements in the ring, the Ulster and Irish titles, the international excursions, the trips and the tales he has to tell, there is one incident that still gnaws at him over half a century on.

In 1966 an 18-year-old Paddy Graham wore the Ulster and Irish flyweight crowns, putting him in pole position for a spot on the Northern Ireland team bound for that summer’s Empire Games in Jamaica.

“Look,” he says, handing over a cutting in which respected boxing journalist Bill Rutherford considered those in contention for the Caribbean.

To Rutherford’s mind, from a likely team of six or possibly seven, there were three cast-iron certainties: light-welterweight legend Jim McCourt, bantam Jim McAuley, and Paddy Graham.

“I had won the Ulster and Irish titles, I beat the defending champion Paddy Maguire of Vauxhall Motors in the Irish final. He was from Dublin but based in England, and he won their ABA championships too,” explains Graham.

“I’d also fought a guy called Tony Humm from England who’d recently beaten a European gold medal winner. I beat him in Ballymena, then I beat the Polish champion down at the National Stadium.

“I thought my record was good enough, and I was told by Jack Dowey [then Ulster Council honorary treasurer] up at Paisley Park that I was number three to go at that time...”

However, on his way back from Paisley Park – home of the Albert Foundry boxing club in west Belfast - a chance encounter with a friend rocked his world to its foundations.

“A fella called Patsy Higgins came over to me and said ‘Paddy, there’s seven picked, it’s only after coming over the television, but you’re not on the team’.”

Gobsmacked, Graham ran back to his parents’ house at Garnet Street.

Dad Peter had watched the same sports bulletin as Patsy Higgins and burst into tears the second his son came through the door.

“It was terrible what they did to me but I was more worried about my daddy.

“My daddy always had a bad chest and when I went down to the house, he was sitting in the chair and he got up. I’d never seen him crying in my life but he was now.

“I was saying ‘don’t be worrying about it daddy, it’s alright, it’s alright’.”

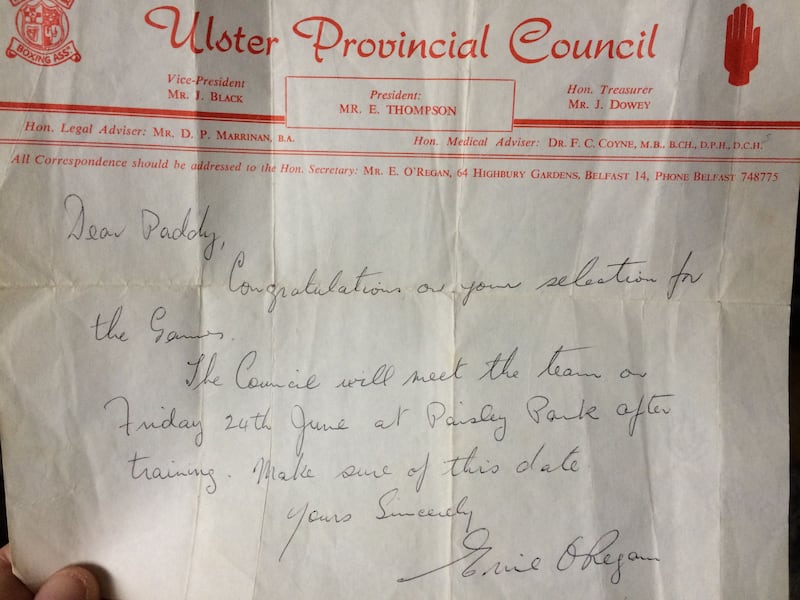

To add injury to insult, a telegram from the Ulster Council landed through the letterbox the following morning.

“Dear Paddy,” it read.

“Congratulations on your selection for the Games. The Council will meet the team on Friday 24th June at Paisley Park after training.

“Make sure of this date. Yours sincerely, Ernie O’Regan.”

His father went straight to the nearest phonebox and tried to get in touch with O’Regan, who was then honorary secretary of the Ulster Council.

“When he saw the telegram he was lifted a bit,” recalls Graham, “but that actually ended up making things worse.

“When he eventually got a hold of somebody, they told him a mistake had been made and that I wasn’t going to the Games. That upset him again – I was scared of him taking a heart attack or something.

“After that we came back to the house and just sat. We were all in shock.”

Years later renowned boxing coach Harry Enright, who took the Northern Ireland team to Kingston, presented Graham with a souvenir handbook brought back from Jamaica.

And on the first page was a hand-written foreword that is cherished to this day.

“21st March – 2011. Forty five years after this book was published I am more than pleased to gift it to Paddy Graham to assure him that his exclusion from the Ulster boxing team was unjustified and unjustifiable,” wrote Enright, who passed away in 2015.

“I never understood the reason or reasons for this exclusion but I have never doubted his ability to have won a medal at flyweight. His subsequent career record is testimony to this.”

Graham stepped away from boxing for a while before eventually making his return as a professional in 1968 – an 11-year, 29-fight journey that ended with a winning record and took him to Melbourne and the Ghanaian capital Accra along the way.

But he has no doubt it was as an amateur where he could, and should, have made his mark.

“I was always raging I didn’t go down and try to win another Irish title and get to an Olympics. Looking back I was far too young to turn pro, but I was just sickened after what happened.

“I still think there was a take-on some way, but I don’t know why,” he adds of his Empire Games disappointment. “To this day nobody has ever told me why I wasn’t picked to go.

“It would’ve been nice to win some kind of medal. There was only seven in the flyweight division that year so you might have only had to fight once and you’d have won a medal.

“It would’ve been nice to even show your brothers and sisters when you came home, your children and grandchildren once you get married.

“But, as life goes on, you realise there’s worse things than that...”

There is a perspective when it comes to pain.

And as Paddy nods towards a photograph on the other side of the room, thoughts of Jamaica and what-might-have-beens drift far off into the ether.

“That’s him there,” he says, lifting a handkerchief and dabbing at his eyes.

“That’s Paul, God love him.”

****************

A coroner has said that there is no evidence of any lack of care by staff at a Belfast day centre after a man collapsed there and later died in hospital over a year ago.

There were emotional scenes at an inquest yesterday after the family of Paul Thomas Graham (28), who died following an epileptic seizure, challenged a version of events presented to the court.

Mr Graham, of McQuillan Street in Belfast, died on June 14 of last year after he collapsed at the Everton day care centre in north Belfast.

Belfast Coroner's Court heard that Mr Graham had learning difficulties and had suffered from epilepsy since early childhood, although he had not suffered any seizures in the six months leading up to his death.

He had been eating his lunch on the day in question and had gone into another room with some banana still in his mouth.

Staff said that a short time later he was seen to be collapsed in a chair and appeared to be lifeless.

Despite attempts to revive Mr Graham by centre staff, paramedics and doctors, all of whom attempted to clear food from his mouth, he died later at the Mater Hospital.

Assistant state pathologist Dr Peter Ingram, who carried out a post mortem examination, said that food from Mr Graham's stomach had been inhaled during the seizure and that there was evidence of stomach acid in the lungs.

Mr Leckey recorded that Mr Graham had died from inhalation of gastric contents due to epilepsy.

Mr Leckey said: "There is no evidence of any lack of care by anyone who attended Paul at the centre on the day in question."

Belfast Telegraph

November 1, 2007

“HE was a brilliant kid,” says Irene, a proud smile beaming across her face. “He couldn’t talk but he knew everything, I swear. He knew what he wanted, he was unbelievable that way. He was 28 when he died but he still looked like a child.”

The events of the morning of June 14, 2006 are seared into the memories of Paddy and Irene Graham. The phone call, the journey to Everton day care centre, to the Mater; the horrible, gut-wrenching feeling of hopelessness.

“He had been going there a lot of years,” says Paddy.

“When we got there, he was just lying there on the floor. I’ll never forget it. The ambulance man was taking his finger out of his mouth… I just started praying over him.

“They said to me ‘Mr Graham he still has a slight pulse’, but I knew he was dead. You’re praying and just willing him to come around, but he didn’t.”

The Graham family remain deeply unsatisfied with the resolution reached at the coroner’s court 12 years ago. Indeed, such was his anger, Paddy was asked to leave the courtroom after challenging a senior staff member’s version of events from the public gallery.

The family still hold the firm belief that Paul died from choking on food rather than from a seizure, and feel they owe it to his memory to keep on fighting.

They have been in regular contact with solicitor Padraig O Muirigh and are determined to find some way, any way, to have the case reopened in future.

“You hear about these whistleblowers in different cases... I just wish somebody’s conscience would get the better of them and they would come forward. That’s what you’re hoping for. To us, the case is still ongoing; we couldn’t let that go.

“People will probably think we’re mad, but me and her still think we hear him in the house here at night. He’s still a part of our lives.”

Paddy and Irene stand at the bottom of the stairs beside the gate, Paul’s gate, the pain every bit as raw now as it was then.

“Poor son,” says Irene.

“He went away that day and never came back to us again… he gave you great love and great laughs, and we miss him every single day.

“We know we can’t bring him back but we’re still on it. You read these stories in the papers and watch on TV where cases are reopened after 15, 20 years or whatever and you think ‘there’s still hope’.

“That’s all we have now; hope. But we’ll never, ever let it lie.”