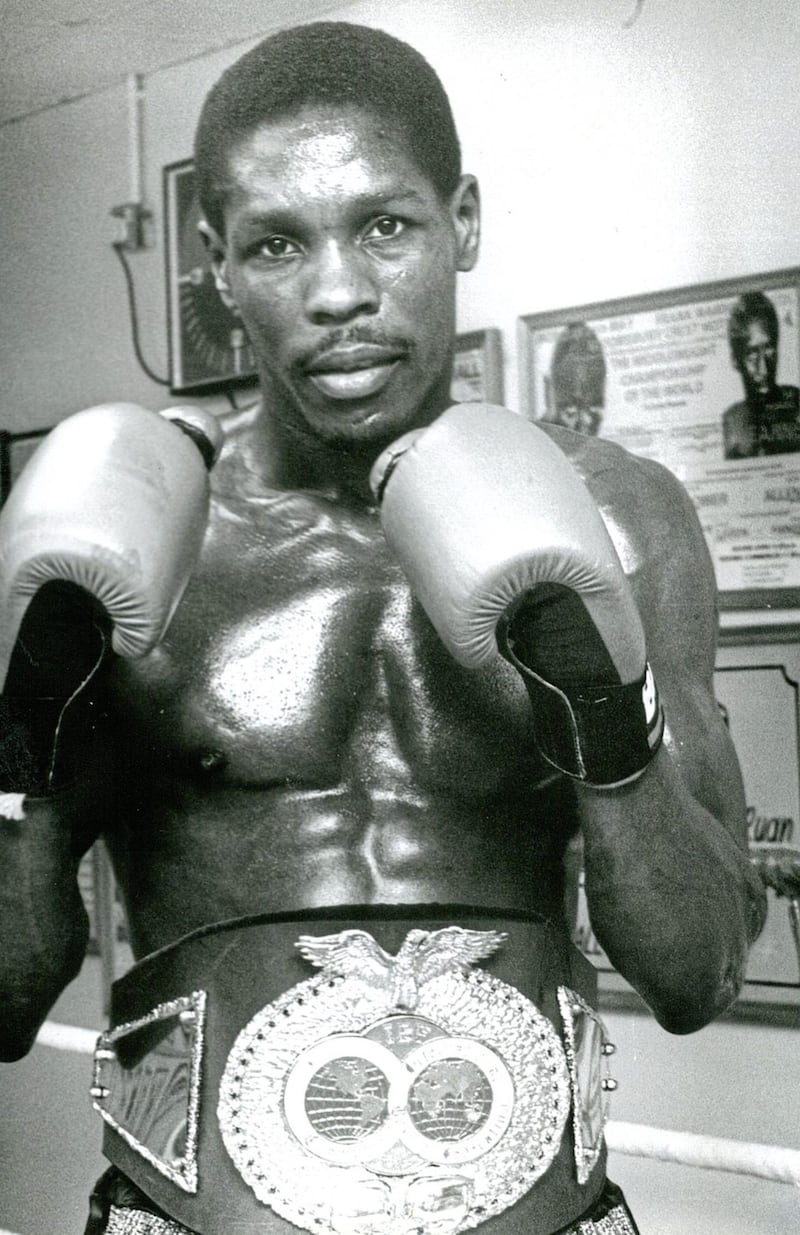

SITTING in the lobby of a London hotel ahead of the biggest night of his life, fight fans tentatively made their way over to wish him well. Crisanto Espana remembers registering the doubt in their eyes, and more.

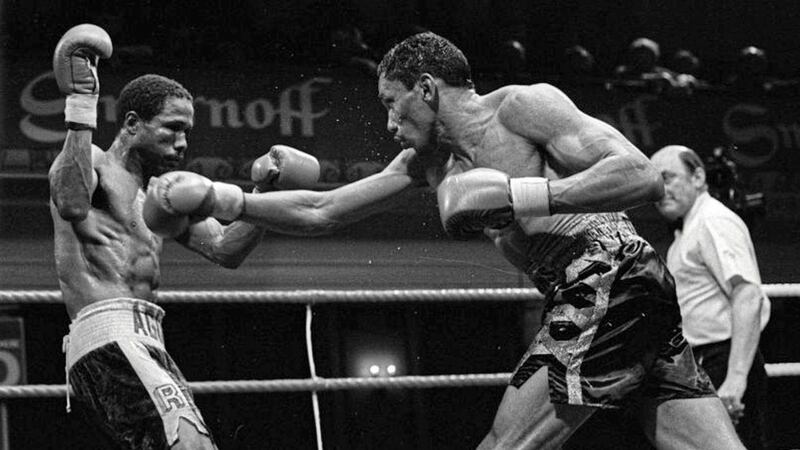

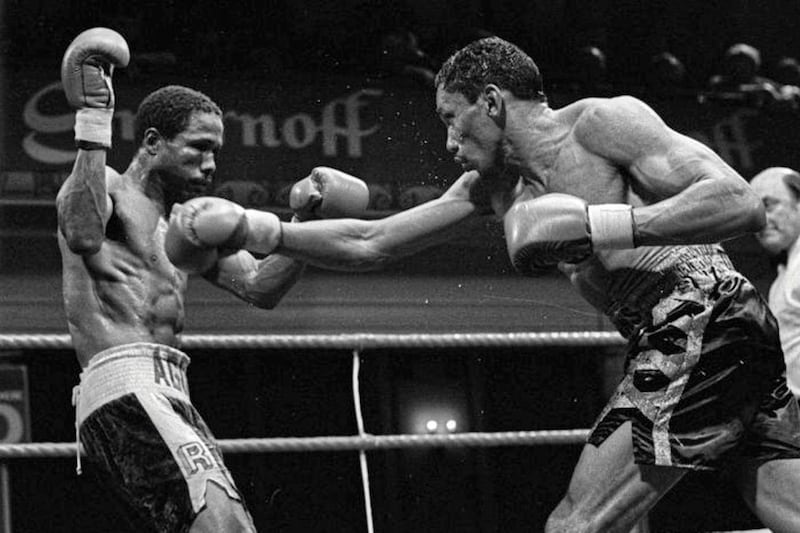

Meldrick Taylor was the overwhelming favourite heading into their October ’92 showdown at Earls Court, chief support to the heavyweight title elimination bout between Razor Ruddock and Lennox Lewis.

Two years earlier, Taylor held a wide lead on two judges’ scorecards going into the final round against Julio Cesar Chavez – then undefeated in a 14-year career to date – before the Mexican legend forced a stoppage just seconds before the final bell.

The American’s pedigree was undisputed, but there were serious signs of decline in his fourth round TKO defeat to Terry Norris five months before sharing the ring with Espana.

Eastwood, Breen and co could smell blood, and the chance to bring another world title belt – the WBA welterweight strap on this occasion - back to Belfast.

“The people in the hotel in London told me ‘you are too skinny, you don’t have any chance’,” recalls Espana 25 years on.

“I told them ‘I will stop him, I will knock him out’. How do I know? Because he was scared of me. When I shake his hand and look in his eyes, I can see. I said to Bernardo [Checa] ‘this boy, he is scared of me. He doesn’t want to fight me’.”

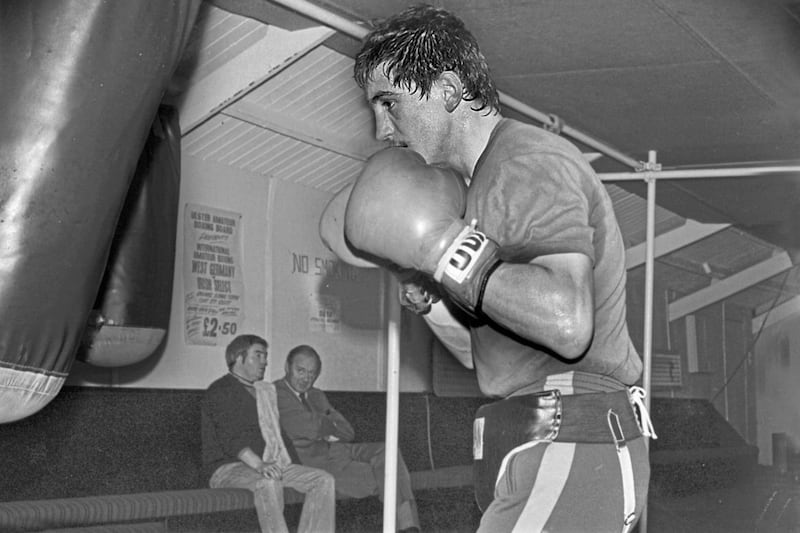

The Troubles were raging but Eastwood's Gym in Belfast was booming

The 5/2 underdog was right as he dominated from start to finish before dropping Taylor in the eighth. Seconds later he sealed the deal with a sickening left uppercut to realise his dream.

“It was the most beautiful night in all my life,” says Espana. “I never felt better than that night.”

“Taylor was a star at the time but it wasn’t a race that night,” adds Breen, who was one of the first in the ring to throw his arms around Venezuela’s celebrated exile.

“It wasn’t a surprise to us because Crisanto had been showing that in the gym every day. Nobody else knew anything about him. Barney did a good job with him because nobody knew just how good Espana was.”

The secret was out now, and after successful defences at the Ulster Hall and then in Manchester, Ghanaian Ike Quartey was up next in Paris in 1994.

Undefeated but largely unheralded, Quartey – who would push Oscar De La Hoya to a split decision five years later - was an unknown quantity at this time.

Yet it was he would signal the beginning of the end for Espana, a thundering left-right combination in the 11th forcing a standing count before another right hand through the guard sent Espana wearily tumbling to the ground.

“It was a hard night. I was winning all the fight, but then I didn’t have the power in my hands. I had never been knocked down in my career before… I don’t know what happened.”

Eastwood and Breen have some suspicions of their own about why the marathon man faded so spectacularly.

“Crisanto used to get stronger as the fight went on but after the second or third round I said to Barney ‘something’s wrong here, he’s not firing on all cylinders’. He just tired more and more, couldn’t get his breathing right, no punching power...

“I was going to Lanzarote from France the next day and I phoned Crisanto on the Monday and there was no answer. Then I phoned Barney and he told me Crisanto was in the hospital, they’d found drugs in his system…”

“He shouldn’t have fought that night,” says Eastwood, taking up the story. “He got nobbled; somebody put something in his food.”

Team Espana had been staying on the outskirts of Paris after travelling to the French capital ahead of fight night.

The day before, Eastwood had to travel into the city centre on business. Before leaving, he issued strict instructions not to eat on the premises. Having been around boxing for so long he had grown wary, and the presence of a shadowy figure at the hotel did little to arrest his suspicions.

“I told the boys not to dine until I came back but when I came back they were all sitting in this wee hotel eating away. I thought ‘Jesus, I don’t like this…’

“There was a wee French fella who had been hanging about - I’d seen him at boxing matches before - and I remember thinking ‘no, we’ll dine elsewhere’.

“I would often have done that. If I had a fighter fighting for a world title, nobody would have ever known where we were going to eat. When you’re away from home, that’s what you have to do.”

On the day of the fight, Espana started running to the toilet with alarming regularity. Even in the moments before the ring-walks, his cup had to be removed so he could relieve himself.

Alarm bells were ringing in Eastwood’s head.

“I told him I was going to pull him out.

“But he said ‘no, I need this fight, I’ll be alright - I can maybe get to him in the early part of it’. It was his call, he wouldn’t hear tell of being pulled out.

“He was sick for days after it, throwing up. This was a guy who could run forever, and he knew he wasn’t well that night.

“Afterwards, the wee French fella said to me in half-French, half-English ‘I did what I had to do’. He admitted he did him up.”

A detached retina suffered in defeat to Quartey led doctors to advise he call it a day. Espana fought just once more, a facile points victory on the undercard of the 1995 Steve Collins and Chris Eubank fight in Millstreet before retiring at just 31.

He returned home two years later, leaving Belfast behind for good.

************************************

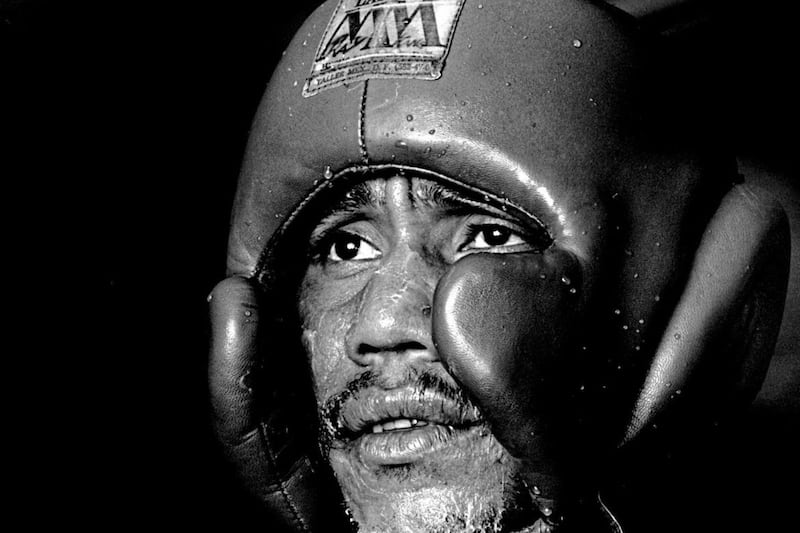

WITHIN the space of a year, Victor Cordoba had made an alarmingly short trip from the most dizzying high to the deepest, darkest low.

Having worked his way up the rankings of a hugely competitive super-middleweight division, the man known as ‘Toby’ back home in Panama finally landed a world title shot.

Cordoba travelled to Marseille for the April ’95 fight with WBA belt-holder Christophe Tiozzo. Undefeated in 27 fights, the Frenchman was as tough as they came.

But the hard rounds in Eastwood’s Gym bore fruit in spectacular fashion when, after nine back and forth rounds, a non-stop assault on the ropes only ended when referee Enzo Montero spared a bloodied and battered Tiozzo any more punishment.

The celebrations went on into the small hours, and eight months later Cordoba returned to France and ended another unbeaten record, this time stopping Italy’s Vincenzo Nardiello in the 11th round.

At 29, the world was at his fists.

These two landmark wins should have propelled him into the very top echelons of a division in which Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn were among the stellar names at the time.

Instead though, Cordoba found himself frozen out and frustrated.

“He won the title in France, beat the guy easy in Paris, but then Benn, Eubank, none of that crowd would fight him,” says Eastwood, with Cordoba adding: “After Nardiello, nobody wants to fight me because I was a hard puncher.

“In England, there was Nigel Benn, Chris Eubank – they don’t want to fight with me. So after I made the first defence, I went for months with no fight, and that’s when I went back to Panama…”

It was nine months, almost to the day, before Victor Cordoba fought again.

In the time between he had left behind Belfast and Eastwood’s Gym, returning to his native land. And it was from this point that his career between the ropes suffered a steady decline.

Cordoba’s first outing under the new regime was against Michael ‘Second To’ Nunn at the Thomas & Mack Centre in Las Vegas. Nunn had some big names on his record, Donald Curry and Iran Barkley among them, but had been flattened by a young wrecking ball called James Toney two fights previous.

Despite the upheaval in his personal and professional life, Cordoba looked to be in control, sending Nunn to the canvas down the back straight.

He even resisted the urge to go in for the kill, such was the belief that he must be miles clear on the cards. Big mistake.

Nunn had just been signed to Don King’s stable and when the words ‘split decision’ were uttered, Cordoba broke into a cold sweat. Seconds later, Nunn’s hand was raised.

‘And the new...’

The American won a dour, disappointing rematch in Memphis four months later, and all of a sudden Cordoba found himself staring into the abyss, wondering where it had all gone wrong.

“I beat Michael Nunn but the Don King people and the judges gave the fight to him. After that, in the rematch, he head-butted me and I was out in the second round. I fought 12 rounds with him but I know nothing about what happened after the second.

“After that, I said I don’t want to fight any more.”

From the point he left Belfast Cordoba fought seven more times – winning three and losing four. It is a decision he regretted almost as soon as he set foot back in Panama.

“I had a good time in Belfast. I was married in Belfast. I remember a lot of positive things but when something bad happened, I lose my mind. I’m not thinking very well and I come back to my country...”

Something bad? “I don’t want to explain too much.

“When I went back I left everything. I left my team in Belfast. I had good coaches - John Breen, Bernardo Checa - good sparring, training every day... I had everything. When I came back to Panama, it was totally different.

“There was no good sparring, it was a disaster. Every time I spoke to John Breen after that I said ‘you have to train me’.”

And, despite his strong bond with Cordoba, Breen had to turn down a lucrative offer to help his old friend ahead of the second Nunn fight.

“He phoned and said ‘John, I need you to push me, I need you to train me’. He offered me £10,000, but when I phoned Barney about it he said ‘he shouldn’t have left us in the first place’.

“£10,000 was some money in those days, but if I’d gone over there I could never have gone back into Eastwood’s when I came back so I said no.”

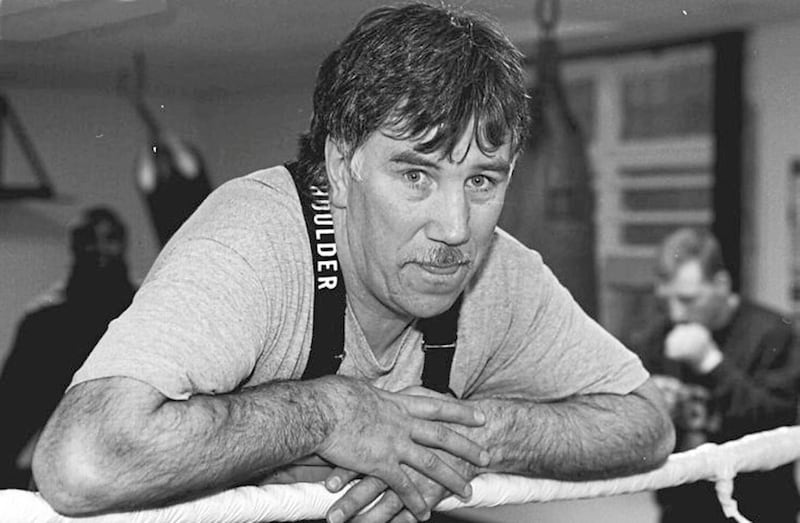

Yet now, decades on, Breen has only fond memories of a glorious era and his time working with Espana and Cordoba.

“Two crackers,” he says with an affectionate smile.

“They were all lovely guys – there were no nasty heads among them. It was the Irish ones and the English ones that caused Barney more problems!

“But the gym was buzzing at that time, everybody in the gym was a champion. I never was in a gym again that was so successful. Barney had three world champions in the one year, it was some achievement by him.

“In those days you just loved going to the gym because you knew you were going to learn something new every day.”

************************************

“NOW it is something different because I have to be in a good jacket every day.”

Inside his office in Panama City is a framed image of Victor Cordoba the boxer – ripped to bits, biceps popping, torso gleaming, in the best physical condition of his life.

But nowadays it is Victor Cordoba the lawyer and politician who pays the bills. After quitting boxing in 1999, he went to Universidad Latina de Panama and within five years was opening his own practice.

“I think I might be the only world champion who is a lawyer.”

A member of the last government under president Ricardo Martinelli, he narrowly missed out on a place in the senate, but hopes it is a position he will hold in years to come.

During his regular phone calls to John Breen, Cordoba makes repeated vows to come back to Belfast. One day, he insists, it will happen.

“I am still speaking to John Breen, and some time I will come and see him.

“I love Belfast. When I was there one time the IRA blew up a lorry – you know, boom! People were doing something wrong but with me and my friends, nobody did anything wrong. Everybody was nice to me.”

Over 1,000 miles away, down through Panama, right across Colombia and out into the centre of Venezuela, Crisanto Espana is running a small boxing school – “just 25 boys” - at his family farm in Ciudad Bolivar.

Unfortunately though, the cash earned from his sporting career did not set him up for life. With a large family, including 14 siblings, money always had to be wired back home.

As a result of that, and the crippling financial situation his country finds itself in (Venezuela currently has the highest inflation rate in the world), times are tough.

And Espana admits wishing he had never bid Ireland farewell.

“I don’t know why I came back; it was a big mistake. I’m not happy now.

“My grandpa was very old, he was very cross with me, I was very cross with him... I don’t see him for a long time, and I didn’t want my grandpa to die and not see him again.

“But life is very difficult here. It’s worse than it was in Belfast in 1990 - it’s very dangerous over here, many people killed. Here, you don’t have anything, no medicines, no anything. Everything is too expensive.

“I always wanted to come back to Northern Ireland but, because of problems over here, I can’t come back. There are many bad boys here - they’ve stolen my car, they’ve stolen everything. Now I have no car because it is too expensive, it costs too much money.”

Both Espana and Cordoba were sounded out about returning for a gala night to celebrate the career of former trainer Breen in 2012 but logistics, and finance, meant it didn’t come to pass.

However, just like his former stable-mate at Eastwood’s Gym, Espana hopes to return some day.

“I want to,” he says.

“I know some day I will come back to Belfast. I don’t know when because it is too much money, but one day I want go back and see all my friends.

“I remember when we weren’t fighting, everybody was laughing. Everything was good. Every day, Barney came to the gym to see the boys in training. It was like a family...

“I have lost a lot. The most beautiful time in my life, I was living in Ireland,” he says with a weary sigh as the conversation draws to a close.

“Thank you very much for remembering me.”