IT was on the bus, after the ’09 Ulster final, when making my usual call to my better half for a quick ‘how are you’ and a chat about the game that I realised I might have a price to pay for Tyrone’s latest victory.

Phone answered with not even a hello was hardly a good omen. “Well...” I said, breaking the silence.

“Well,” came the terse reply.

We had just beaten Antrim, for whom two of my wife’s brothers, Tomás and Michael McCann, and her brother-in-law, Tony Scullion, were key players.

Hailing from Cargin on the loughshore, it’s fair to say the ‘humble in defeat’ approach wasn’t her forte.

The conversation was stilted as expected, but then the tone darkened.

“What about the tackle on Tomás?”

I tried an initial “What was that?”, feigning innocence, but I knew rightly what she was on about.

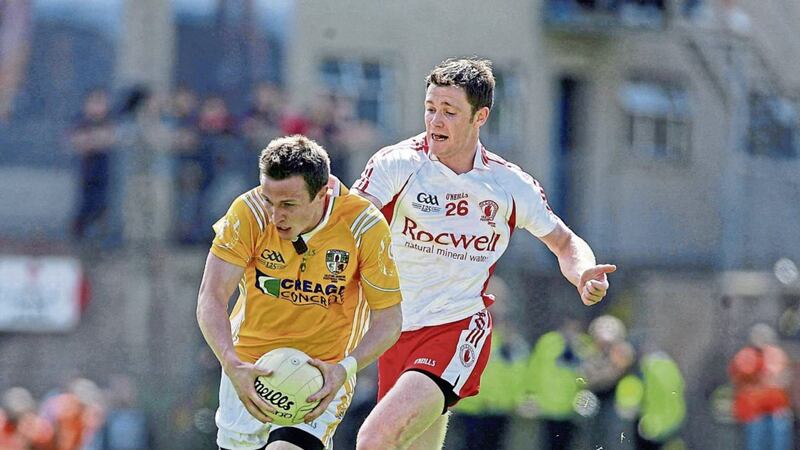

I hadn’t started the game due to a dodgy hamstring but, given the nature of the family involvement, had pushed hard to get back in contention and was duly thrown on with about 20 minutes to go. Antrim had got on a bit of a run, narrowing the game to five points when Tomas was released through the middle and I happened to be the man in pursuit.

Tomas was a flying machine (who likes to tell me he still is). We had identified him as a threat with his ball-carrying pace and, having waved goodbye to my own version of ‘pace’ a year or two before, I was in a vulnerable position. As any man knows, some things can be forgotten about, but a skinning on a football pitch by your younger brother-in-law isn’t one of them.

A goal at that stage would’ve made the match too close for comfort, so it was important a ‘tackle’ was made.

Having trained and played alongside ‘Ricey’ McMenamin and Conor Gormley for long enough, I knew well the skill of blending the ‘attempted tackle’ with the ‘stop them tackle’ into one.

It may work out a good tackle, it may not, but the job gets done. My ‘attempted tackle’ brought Tomas down for a free. In the stand, my wife, rose to her feet to admonish whatever “dirty *******” had fouled Tomas. Informed of my identity, it’s fair to say any semblance of love or split loyalties were long gone.

Of course, and again Tomas would beg to differ, there was no guarantee he would’ve scored the goal if he did get through. Photographic evidence of ‘Ricey’ in the vicinity meant if my tackle (I’m still calling it that) had failed, the much more seasoned assassin would have ‘attempted to tackle’ him too, so my intervention was hardly decisive.

None of that matters, of course, and the whole incident has been logged as a black mark against my name ever since.

Fermanagh and Donegal, of course, don’t need reminding that such small moments decide big games.

Michael Murphy missed a free to go two up in the dying moments in 2016 and gave Tyrone the hope which led to Sean Cavanagh and Peter Harte’s game-winning wonder points.

For Fermanagh, Ryan Keenan’s missed free in 2008 in the drawn game with Armagh was the moment a first Ulster title slipped from their fingertips.

Big moments only happen in tight games and that’s Fermanagh’s big – but not impossible – task on Sunday – bring this game down to the wire then let fate roll its dice. If Fermanagh are still in with a shout come the final five minutes, there will be an unmerciful weight of history pushing them towards the line.

Only two teams in the country, Fermanagh and Wicklow, remain without a provincial title. Fermanagh have brought so much to the table in the last two decades alone that they deserve not to be in that dubious group.

The last first-time winner in Ulster was in 1972 – none other than Donegal.

We are regularly told Fermanagh has only 20 clubs yet that seems to create something where every man, woman and child out there with Erne blood (including Arlene) feels an attachment to it.

Going back to that Ulster final in 2009, something I had to agree with my wife on (when we eventually talked) was how the complete lack of celebrations by Tyrone players and supporters did not reflect well on us considering what it would have meant to Antrim then, or, indeed the likes of Fermanagh this Sunday.

I remember the Anglo-Celt Cup sitting in the middle of the dressing room and not getting a second glance.

For reaching the final, songs and poems have already been written and goats and cars painted in the Erne county. If the Quigleys and co get their hands on the

Anglo-Celt Cup come Sunday afternoon, it will not have as quiet a time.

So what are Fermanagh’s chances? This final mirrors last year’s final, in which Down, having coincidentally toppled Monaghan, were surprise participants but ended up easily beaten by a Tyrone team who cruised through their Ulster campaign – not unlike Donegal in this campaign.

The difference may be that where Down started to believe in their ‘swagger’, only for it to disappear as suddenly as it had appeared, Fermanagh’s belief is based on more dependable foundations of work rate, defensive solidity and team spirit.

The big dangers for them will be a good start by Donegal, forcing them to chase the game, or that Donegal have simply too many scoring options, including from distance, for Fermanagh to nullify like they managed against Monaghan.

For Donegal, the absence of Neil McGee when up against a physically powerful full-forward line is a concern.

The biggest question, though, is over the big game quality of their players.

Vaunted last year before being demolished by both Tyrone and Galway, they have again impressed massively in early season fare.

Fermanagh may or may not provide a litmus test, but if Donegal do claim the provincial title it would add substance to this team’s lofty potential.

Both Fermanagh and Donegal are no innocent teams, so finding that fine line between discipline and aggression will be key.

Declan Bonner has been stirring the pot this week by suggesting Ryan McHugh needs protection. McHugh, of course, is in flying form and will be a key figure for Fermanagh to stop, but he knows exactly what he is at in terms of winning frees.

By dipping across a tackler head first, he arguably invites the appearance of a high tackle that refs are known to be stamping down on. No fewer than seven frees were won against Down in this manner, so who is targeting who?

It’s hard not to hope for a Fermanagh win but, even allowing for the defensive smarts of Rory Gallagher and ‘Ricey’, it’s hard to see how Fermanagh can halt so many talented players IF, of course, that talent stands up to be counted.

As always it’s head v heart. Head says Donegal with ease, heart says Fermanagh by one.

An Ulster final, though, is no place for love... so it’s Donegal for me.