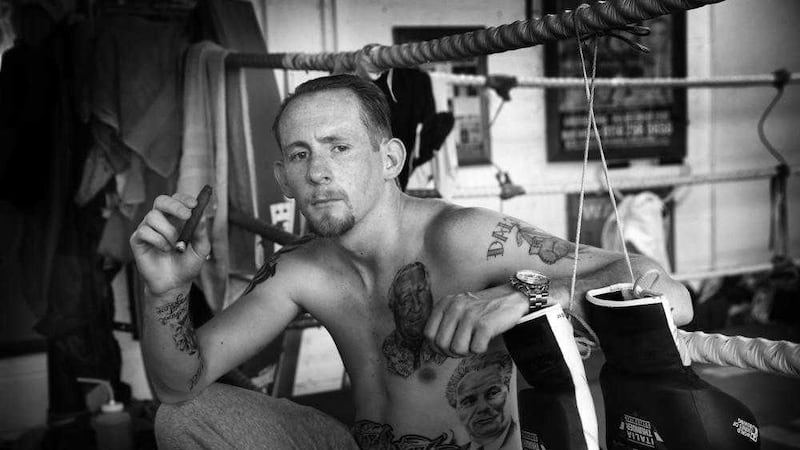

MEET Ruairi Dalton. Gangster lover, tee-totaller, coffee swiller, cigar chugger, gambling addict, gambling confidante, story teller and, soon, professional boxer.

Since his older brother Joseph first held up pillowcases as makeshift pads, Dalton has been drawn to the fight game. The buzz, that raw, primal surge in the pit of the stomach when you step inside the ropes and eye up your opponent – he lives for that feeling.

Dalton was a high quality amateur, mixing it five times with Olympic gold medal hope Michael Conlan, beating Conlan’s brother Jamie and competing at the Commonwealth Games.

Fleet of foot, loose limbed, blessed with fast hands and even faster reflexes, Dalton has always cut a flamboyant figure in the ring. Under the tutelage of veteran trainer John Breen, he hopes to transfer those skills to the paid ranks.

But more of that later - because if Ruairi ‘Rook’ Dalton is an entertainer between the ropes, his story away from boxing is as colourful a tale as you are likely to hear.

Born Ruairi Maurice Dalton on July 8, 1990, he was raised in a loving home in St James’s, off the Falls Road in west Belfast, by mother Geraldine, growing up alongside Joseph and sisters Aisling and Helena.

Granda Robert Carnahan lived across the road and kept a close eye on the young ‘Rook’.

On a torso that is a tapestry of needle and inkwork nodding to some of the biggest influences on his life, an image of his smiling granda – who passed away in 2014 – with the slogan ‘I did it my way’ is as a permanent reminder of the man who helped shape him.

But eventually Ruairi started to wonder why his friends had dads and he didn’t. Why he was the only Dalton in the house.

At “six or seven” he recalls asking for the first time who his own father was - and being thrilled at the response.

“My ma just pointed towards the TV and said ‘that’s your da there’. It was Hulk Hogan.

“I thought my da was Hulk Hogan until I was nine or 10! I actually started crying when she showed me photos of my da later on, saying ‘I thought Hulk Hogan was my da…’

“I was gutted.”

He may not have been a hotshot wrestler and star of the silver screen, but the first meeting with his father was no less like something from the pages of a Hollywood script.

IIIIIIIIIIIOOOOOIIIIIIIIIII

'A 31-year-old bank robber with a penchant for luxury hotels was arrested last night in an Upper East Side hotel a day after carrying out his 14th successive robbery, the police said.

The man, Sean Martin Dalton, was arrested in the Doral Inn on Lexington Avenue and charged with first- and second-degree robbery and criminal possession of a weapon.

Detective Walter Burnes, a Police Department spokesman, said that Mr. Dalton robbed the banks, in Brooklyn, Queens and Nassau Counties, between Dec. 1 and Thursday. Mr. Dalton stole $54,880 from 12 banks in Brooklyn and Queens and $4,360 from two banks in Nassau County, he said'

New York Times

January 31, 1998

A COUPLE of letters went back and forth across the Atlantic, but the first time Ruairi Dalton came face-to-face with his dad was at the Arthur Kill correctional facility on Staten Island in 2003, six years after his initial incarceration for robbing banks around New York.

Having travelled to the ‘Big Apple’, Dalton has a vivid recollection of everything that happened that day. The expectation, the reality. That long-awaited first conversation, father and son.

“We wrote to each other for two years, and he wrote to my mummy, and his mummy booked me a flight. I was 13 then, and I’d only seen photos of him in jail.

“In the pictures he had long hair but when I went to see him – me, my granny and my sister came over – I said ‘is that my da?’ He was a big skinhead at the time, built like a tank.

“Me and him were brought into a room and sat beside all the other prisoners and their families - it was like something out of a film.

“When we spoke for the first time, he was just talking about life, trying to put me in the right direction, telling me not to be doing the things he did. He said this is a place you don’t want to be, this place is not for you.

“For me though, it was just a big relief to finally meet him and sit down with him.”

Born and raised in the New York borough of Queens, Sean Dalton came to Belfast in the late 1980s, his journey one of necessity rather than design.

Son to a mother from the Short Strand, Noreen Dalton, he stayed with relatives after mounting debts accrued through drug dealing saw him run out of town.

He met Ruairi’s mother Geraldine and the pair were an item for 18 months before a fall-out with a high-ranking Republican saw him on a flight back to New York, never to return.

With a drug problem of his own, and a bounty on his head for money owed, Dalton senior turned to robbing banks in a last-gasp effort to bring an end to his financial woes.

His life had spiralled out of control to such an extent that being caught was almost a relief. Sean Dalton’s 11 years inside were spread across seven different jails and when he was released, forging a relationship with his only son was the top priority.

“I went over to visit him in 2008 when he got out, stayed in his house and that was weird because I’d only met my dad in jail five years before that for an hour.

“But we just got on straight away. Even the looks, we’re the double of each other, the ears and everything – there’s no need for a DNA test there. Personality wise, there’s a lot of things I’ve taken after him even though he wasn’t there. It’s crazy.”

On his right forearm, Ruairi wears with pride a tattoo of the ‘Wanted’ poster issued for his Stetson-cap wearing father when he was at his bank-robbing height. Sean Dalton has the exact same image on his left forearm.

“You forgive and forget,” Ruairi says when asked if there is any resentment towards his father for missing those early years.

“He was just nuts at the time, on drugs, and I think that haunts him. But now, we talk all the time. I’m going out to New York in August with a few friends to see him.

“And every day I see him now, whether it’s through Facetime or whatever, I feel relieved.

“He’s always been very honest with me, always saying that what he did was wrong. When I went over when I was 18, he told me all the detail. He always told me to be a man’s man, and I hope I am.

“A lot of people take their family for granted and argue with their ma and da all the time, but see every time I see my da? I feel class. It’s a big thing for me.”

IIIIIIIIIIIOOOOOIIIIIIIIIII

IN many ways, Ruairi Dalton is a walking contradiction. Ask him who his favourite fighters of all time are, and he’ll namecheck two of the maddest dogs to ever lace up a pair of gloves.

“I loved Johnny Tapia, just the stories about him, the way he fought, and Hector Camacho – he was a crazy guy, but what a boxer. Just brilliant.”

Perhaps because of his father’s wild past, Dalton is fascinated by guys from the wrong side of the tracks. Men who are as famous/infamous for their antics outside the ring as inside.

Yet the 25-year-old has never had a drink. Never touched drugs. The odd Cuban cigar and a long cup of coffee are his main vices.

“See when you’re looking at people with hangovers, you just think ‘na, f*ck that’. Give me a coffee and a cigar and I’m a happy man.

“I went to Ibiza with my mates last summer, everybody was doing what they were doing, and I was just sitting there with an Americano before we were going out.”

That discipline certainly helps when it comes to the noble art.

After those early sessions of the pads with his brother, Dee McConville and Frankie McCourt were the amateur coaches who helped Dalton take his first steps in the sport.

Indeed, it is McCourt he has to thank/blame for offering him the chance to fight Rau’shee Warren in Kildare back in 2009 – “the best I’ve ever shared a ring with”.

The Cincinnati native was crowned WBA world bantamweight champion eight days ago, and is seen as one of golden boys of American boxing.

When he was slated to meet Dalton, Warren had won flyweight gold at the World Championships in Chicago two years previous and was already being tipped for the big time.

Not that the Belfast man had any fear – until he watched some footage of his next opponent.

“It was my first and last time fighting for Ireland,” he recalls.

“A couple of people had pulled out of fighting him and I remember Frankie phoning me. I was lying in bed, it was about 10 in the morning, and he said: ‘Do you want to fight Rau’shee Warren?’ I knew who he was and I was like ‘yeah, I’ll fight him, f*ck it’.

“I was down in the Park Centre later in the day and went into an internet cafe and looked him up on YouTube. There I was watching him stopping one, stopping another, knockout after knockout, slipping down in my seat. I was like ‘Jesus Christ…’ – the sweat was lashing off me.

“Frankie said ‘are you sure now?’ but I still took the fight. I was only a kid, and standing in the centre of the ring looking at this guy, arms popping, muscles everywhere, dreadlocks, he just looked the part.

“I thought ‘if I can take him the distance here that’d be brilliant’. He beat me 20-9 but I did well, I was delighted with that. It was a brilliant experience.”

That was just the start of the journey and, after being pipped by Michael Conlan in a box-off to go to the 2010 Commonwealth Games – only a point separated the pair - Dalton made a promise to himself that he would be in Glasgow four years later.

Now boxing for the famous Holy Trinity club in Turf Lodge, he negotiated the first two rounds comfortably before falling to eventual champion – and current 8-0 professional – Australia’s Andrew Moloney, just missing out on a medal.

It was a hugely positive experience, but he knew then and there that he was finished with the amateur game. The death of his granda later that year rocked him to his core – boxing was the last thing on his mind.

At this stage, gambling started to strengthen its grip on Dalton.

“Whatever money I made I’d be straight down to the bookies on a Monday. I’d have gambled on anything – greyhounds, horses, I played the machines. That was my drug. It was just boredom, and a lot of my mates are gamblers.

“There’s nothing as bad as walking out of that bookies depressed. Walking in with money and walking out with nothing - that’s a terrible feeling. There was plenty of times I just said ‘I’m not going training’, my head’s melted. It has a bad effect.

“Gambling has played a big part in my life. Every day I get the sweat, you never lose it, but you just have to walk by that bookies and you feel good when you do.”

After a relapse earlier this year, Dalton has been gambling free for four months and, along with friends who found themselves in a similar position, set up a Gambling Anonymous course in St James’s every Friday night. So far, so good.

Hooking up with the experienced John Breen has helped refocus the mind too, and turned his attention back to the sport he loves.

“John accepts you for who you are. I just do what he tells me and as long as you put the work in, he’s happy.”

Despite being out of the game for the best part of two years, Dalton has felt good - like he has never been away.

The plan is to make his debut at super-bantamweight next October, and he can’t wait to feel that buzz, that surge of adrenaline all over again.

“Going to the Frampton fights when Dee [Walsh] would be on the undercard - Dee’s one of my best mates - that’s when I really knew that was what I wanted to do.

“Getting into the ring, you’re nervous, really nervous, but after 30 seconds that’s gone and there’s no better feeling.

“I want to be active. I’m not afraid to take a loss. A lot of people here are fighting 12 and 13 fights against nobodies – I know you have to start off that way, but after 10 fights I’d be happy fighting anyone. The crowd need that – they don’t want to go and see a fight that’s over after two or three rounds.

“You’re supposed to be learning. That’s why the Mexicans are so good, because they’re at it from early and if they lose, they lose. Move on to the next one.

“It does no harm to get thrown in at the deep end sometimes.”

With all that life has thrown at him so far, the deep end of boxing should hold no fear.

Getting to the top is the dream, the same as any young man starting out. It’s a long road, Ruairi Dalton knows that better than most.

No matter what happens, it promises to be one hell of ride.