Oisin McConville

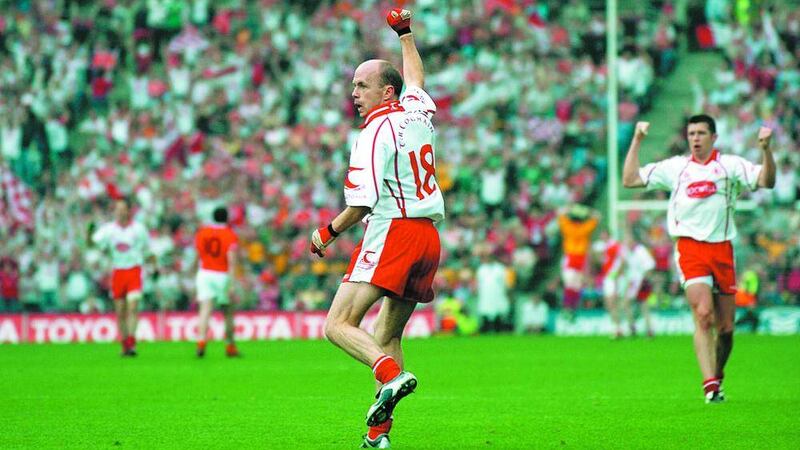

IT WAS well into the last minute of the 2007 All-Ireland club final at Croke Park and Crossmaglen Rangers were a point behind against Kerry champions Dr Croke’s.

As the Kerrymen steeled themselves to defend their narrow lead at all costs, Oisin Mc Conville ran onto a pass with his back to goal about 30 yards out on the Hogan Stand side, but was immediately forced further and further back down the field by opponent after opponent, tackler after tackler, in a circular run across toward the Cusack Stand side, desperately fighting to hold possession and, almost on the 50-yard line, looking for an opening for a shot.

The seconds were ticking away and at every moment he seemed to be on the verge of being dispossessed, of over-holding, on the point of sheer exhaustion.

Then, a narrow opening suddenly presented itself and out of this he delivered a monstrous kick toward the goal, on and on, and that ball refused to come down until it had crossed the bar. The white flag raised by the umpire w as one of surrender to an overwhelming moment of gaelic football. The Rangers went on to win the replay.

The key to Oisin’s greatness was the combination of enormous work-rate with prodigious finishing. Every game throughout his years at the very top in club and county football enacted this formula. As self-confident as he was fearless, his career was full of superb match-turning moments, when time after time the heart over-ruled the doubts of the head, and he defiantly went for scores that were not in the book of football.

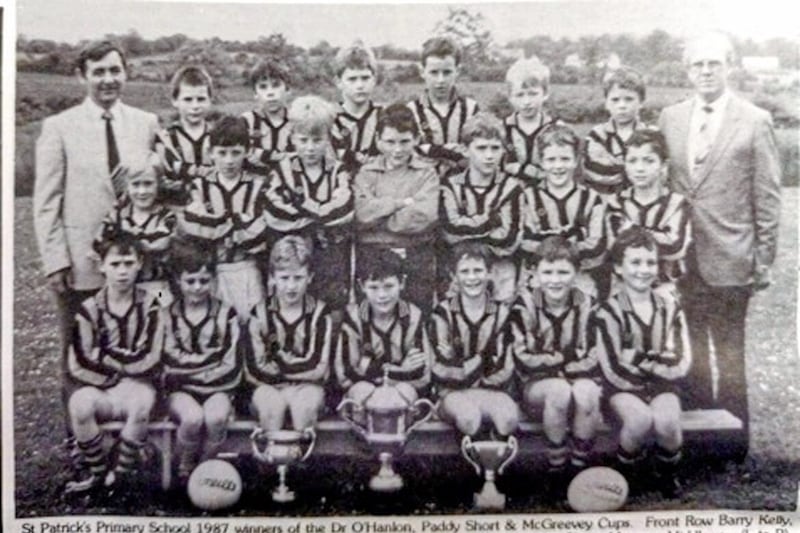

Oisin was born in 1975 into a Crossmaglen family of football pedigree. His uncle Gene Morgan played for Armagh in the All Ireland final of 1953 and his older brother Jim also played for Armagh seniors as a very gifted scoring forward. Under-age football was very well organized at the Rangers club and at the age of 12 Oisin first put on the black and amber jersey and those watching on the sideline got a glimpse of the very early prodigy as he stepped into the arena of destiny.

This was his natural habitat as he moved up the ranks into minor grade as the promising early skills grew and grew past all expectation until at 19 a superb athlete with extraordinary scoring ability was ready to challenge the gaelic football world.

His arrival into senior action coincided with the revolution in the club created by Joe Kernan’s leadership in the mid-Nineties and with a re-organisation of the Armagh senior team under Brian McAlinden and Brian Canavan.

Oisin was a critical factor in the success of both sides. His free-taking, general scoring faculty, and sheer work-rate gave critical possibilities to both Crossmaglen and Armagh that they simply did not have without him. This follows the cardinal rule that all outstanding teams must have a natural scoring forward in their ranks. A team can be excellent everywhere else in the field but the scoreboard will respond negatively at the end of the game if the key ingredient is not there.

Oisin made his Armagh senior debut in the Dr McKenna Cup final at Clones on September 25 1994 and from then until his final county game in 2008 gave an unparalleled service to Armagh and to the overall glory of gaelic football as a sporting spectacle.

The all-time top scorer in Ulster Championship football with a tally of 11-197 (230), he also holds the record for the highest individual score in an Ulster Final, 2-7 against Down in the 1999 Ulster Final.

His even longer reign with Crossmaglen at the highest level and among genuine serious competitors at national and provincial level involved a year after year consistency of greatness on the field of play in every respect that sets him on a special pedestal among the masters of the game. He was top club scorer in Ireland in four of Crossmaglen’s six successful All-Ireland campaigns.

Perhaps his overall dynamic – boundless work-rate and supreme scoring ability – was best exemplified by his goal for Armagh against Kerry in the All-Ireland final of 2002, the most critical score in the history of Armagh county football.

It came out of a run begun by Diarmuid Marsden, who delivered the ball on to Andrew McCann and, after fending off two Kerry tacklers, McCann sent it on to the speeding McConville. He headed toward the goal with serious intent, knowing that he must deliver now or never on the biggest stage of all, in the biggest hour of all.

He kicked ahead toward the in-running Paul McGrane and strode on to take the return. Fifteen yards ahead of him a narrow space appeared between the Kerry ’keeper and the post, and out of the depths he filled it triumphantly with the shot that turned the game.

A few weeks previously he had engineered the winning point against Dublin in the semi-final, fighting off extreme close attention in the dying minutes to fist over the bar.

His art involved a powerful will to win, the ability to do what the will demanded on the field of play and the scoreboard so relentlessly and brilliantly for so long.

As well as his All Ireland Senior medal, McConville holds two Allstar awards (2000 and 2002), seven Ulster Senior Championship medals (1999, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2008) and a National League medal (2005).

He won six All-Ireland Club medals with Crossmaglen in 1997, 1999, 2000, 2007, 2011, and 2012, holds 10 Ulster club Championships and 17 Armagh senior club Championships. He announced his retirement from football in February 2013.

Peter Canavan

IN THE Tyrone years BC (Before Canavan) probably the most iconic scoring forward was Dungannon’s Iggy Jones, whose reputation was made in the ’40s and ’50s with St Patrick’s College, Armagh and later with the rise of his county onto the national scene in 1956 and 1957.

He scored 3-4 in the first ever All-Ireland colleges football final held in 1946 and was the attacking dynamo of county and club teams throughout his era.

Frankie Donnelly from Carrickmore was also a prominent scoring forward during this period.

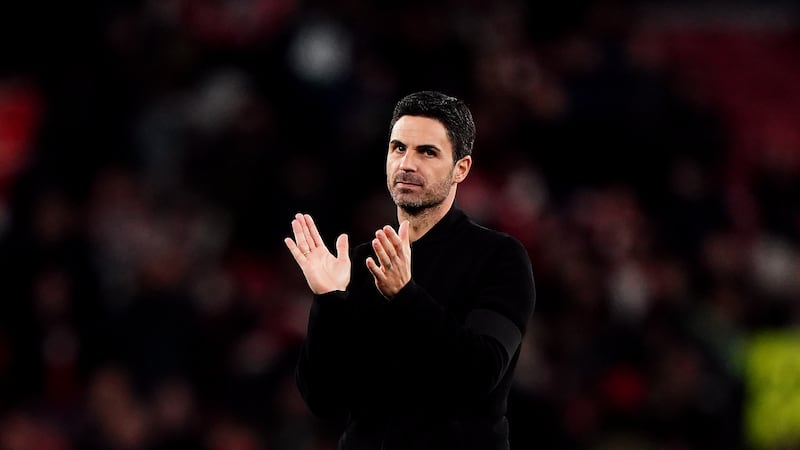

But on April 9, 1971 another prodigy was born into Tyrone who would far surpass the old masters in a career that brought a distinctive brilliance of the art of Gaelic football and placed him among the greatest of all forwards.

The career of Peter Canavan, from Glencull near Ballygawley, is totally documented as befits one of his status from his early minor days for his club and county. He began entering national prominence when he captained Tyrone to two All-Ireland U21 Football Championships titles in 1991 and 1992 and scored 13–53 in those campaigns.

A full 10 years before his won his second All-Ireland senior medal his status as a footballer of superb ball control and clinical finishing asserted itself in the Championship campaign of 1995 with round after round of scoring exploits.

He scored eight points against Derry in the Ulster semi-final, 1-7 against Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final, and 11 of Tyrone’s 12 points in the final against Dublin, finishing Ireland’s top scorer that year with a total of 1–38.

In the first All-Ireland-winning year of 2003, he amassed a total of 1–48, including 11 points against Down in the replayed Ulster final.

Canavan was a scoring phenomenon for Tyrone and Errigal Ciaran at all levels for more than 15 years and was the great creative force on the field of play in that golden era.

So how can his specific art be summed up?

Canavan’s sheer fluency and speed of co-ordination, of ball control, balance, sense of position – and all consummated by supreme finishing ability – are unsurpassed.

There was also a steel edge to his art that rivals for his crown such as Colm Cooper do not possess, a toughness and defiance borne out of ‘having to look after himself’ from an early age.

Along with Australian Rules, Gaelic football involves an equal faculty of hand and foot in the dynamic of the game.

Soccer is almost strictly footwork, with the head as a supplementary factor, while rugby deals in hand speed, with kicking

confined to seeking touch or conversions.

For the greats of soccer, Messi, Maradona, Best, Zidane, this involves supreme footwork, balance, timing and equal scoring ability. For the greats of Gaelic such as Canavan, this involves supreme hand / foot coordination, balance, timing, and scoring ability to match.

The case could be strongly made that the masters of Gaelic football in the full flow of their art display an all-round virtuosity to match that of the professional masters in any other team sport.

From watching him in action on many occasions, it was revealing to see how Canavan could hold possession by that superior

half-second reflex to avoid a tackle, and in the same move unbalance another tackler before they could reach him.

This went on and on throughout the game in which he retained clarity of vision all around him as to how a fresh attack could be engineered.

His art was a seamless flow. The accuracy of the passing was uncanny, the tenacity relentless, the scoring sublime.

Such genius cannot be sourced to coaching skills or training grounds.

Skills can be honed in training. Scientific methods for example have been introduced into Rugby regarding kicking penalties and convertions so that missing is now the exception at the highest level.

But this does not explain how the ball would simply ‘obey’ Barry John of Wales, or the great free-takers of gaelic football with their simple, instinctive kicking.

What Canavan and the other master scoring forwards could do on the field of play can be sourced only to nature itself, that he, like them, was born with a natural superior co-ordination that gaelic football brought to life.

There is no great mystery to this. Supreme reflexes, co-ordination, and accuracy are merely a variation of normal reflexes that make their way up the genetic pool from distant generations and beyond that again to the dynamic of life itself.

Artists, composers, singers must perfect their gifts to reach the top, but there is always an intuitive, resident core of things that presents itself for such honing.

This intuition was perfectly enacted in his famous goal against Kerry in the All-Ireland final of 2005 when a big score was needed.

A long kick toward the goal was well caught by Owen Mulligan, who fought off some desperate Kerry tackling to retain possession, saw Canavan moving toward him at speed, and timed the pass perfectly into his stride with the goal about 15 yards away.

There was no reasoning process involved – to blast the ball, to chip it, or to drive it low and hard.

Pure instinct asserted itself in the strike, pure nature, and the ball sped along the ground to its destination, like a hare

going through a gap in the hedge.

More than halfway through the second half, and with victory still uncertain, he sped into a free space almost on the sideline on the left hand side about 20 yards out, took the pass and, from a most challenging angle, fired over a sensational point to put his county on the home straight.

Such artistry had graced the fields of Ireland and Tyrone for a decade and a half, a relentless flow of supreme skills that all who saw him play knew without a doubt that they were watching one of the immortals of the game.

Peter Canavan retired with six All Stars Awards, two All-Ireland senior titles, four Ulster titles, two National Leagues titles, two All Ireland U21 titles, and for his club six Tyrone Senior Championships and two Ulster club Championship titles.