AS a kid, I was convinced Diego Maradona was sent from the heavens. It was the summer of 1986.

I couldn’t wait for the World Cup to start. There was nothing more exciting than watching the games from far-flung Mexico.

I remember parts of the 1982 World Cup but the finals in Mexico four years later was my first proper World Cup.

We spent everything we had on our sticker books.

I had a stash of blank VHS tapes – Scotch (‘Re-record not fade away’, sang the TV ad) – so I could keep all the best games for posterity.

Thirty-one years on, those same Scotch VHS tapes are still in residence, in a box under my bed, still playable, still as precious as they were in 1986.

A feast of football awaited us. Maradona, Zico, Socrates, Michel Platini, Emilio Butragueno, Preben Elkjaer, Michael Laudrup, Igor Belanov, Hugo Sanchez, Karl Heinz Rummenigge and Jan Ceulemans.

This was long before satellite dishes were drilled to the side of our houses, a time before Sky Sports came into our living rooms to dull our senses and kill our imagination.

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of Maradona and Argentina’s triumph under a blazing Mexican sun, Argentine journalist Daniel Arcucci has ghost-written Maradona’s account of that unforgettable summer, entitled ‘Touched by God: How We Won the Mexico ’86 World Cup’.

It was first published in Latin America last year to remember the finals 30 years on and was translated into English only recently.

Arguably the book’s greatest strength is that it feels unmistakably like 1986 all over again.

It is rough-edged in parts but I loved every page.

They say you should never meet your heroes. It's the same with reading their autobiographies.

During and after Mexico '86, I idolised Maradona.

What I didn't know watching Maradona mesmerise opposition defences back then was that he was hooked on cocaine.

He was first introduced to the drug when he moved to Barcelona in 1981.

He insists he never used the drug during the month-long tournament in Mexico where his undisputed genius was revealed to the world.

“Do you have any idea the player I would have been if it weren’t for the drugs? I would have been that player you saw in Mexico for years on end,” Maradona writes. “That was the happiest I have ever been on a soccer field.”

Arcucci does a valiant job in assisting with the narrative.

It reaches and reveals the small, day-to-day detail of the Argentina camp in Mexico: the fun, the fall-outs, the training, the matches and the heat.

It is a much better effort than Maradona’s first autobiography, ‘El Diego’, which meanders and rambles and is heavily coated in self-righteous clap-trap.

Maradona still has his self-righteous moments in Arcucci’s book but it is more layered than ‘El Diego’. And there is a previously unseen modesty in the legendary footballer.

After his wonderful second goal that beat England in a memorable quarter-final, team-mate Jorge Valdano said to him in the changing room afterwards: ‘Diego, after today, there’s no doubt in anyone’s mind: you’re not only the best player in the World Cup; you’re the best player in the world.’

Clearly moved by Valdano’s tribute, Maradona writes: “That was really something to say – you had to work for something like that.”

Not one predisposed to lofty praise, Maradona’s father told him: ‘Son, today you scored one hell of a goal.’

“My old man,” Maradona writes, “wasn’t big on compliments.”

It was surprising to find Maradona needed validation from his father and team-mates.

Some yarns are obviously rehashed from ‘El Diego’ but Arcucci manages to tell them with infinitely more clarity.

Maradona has always made a big play out of the power struggle he had with 1978 World Cup winning captain Daniel Passarella on the eve of the ’86 finals.

Manager Carlos Bilardo announced Maradona would captain the team, much to Passarella’s chagrin. Both players clashed during team meetings in camp.

In a battle for the hearts and minds of the squad, Passarella, 33, accused Maradona of drug-taking to which the new captain hit back at the defender’s mistresses in Monaco and how he ran up a huge phone bill (2,000 peso) in the team hotel without admitting it was him that had actually made the calls.

“What Passarella didn’t know was at that time telephone bills in Mexico were itemised,” writes Maradona.

“And it was his number, the b******! He was earning like $2m a year and he played dumb about the phone bill for 2,000… He was making us all pitch in to pay for the calls, and he thought it would never come to light.”

Valdano and squad member Ricardo Bochini of Independiente – the latter a hero of Maradona’s – were in Passarella’s camp before the mystery behind the phone bill was revealed.

It transpired Passarella suffered injury and was ill just before the finals and never kicked a ball in Mexico.

Had he been fit, no-one would ever have heard of Jose Luis Brown, Passarella’s stand-in who emerged as one of the best defenders of the tournament.

‘El Tata’ Brown, who couldn’t command a place with his club side Deportivo Espanyol that year, never played as well in his modest career as he did in those seven games in Mexico, the highlight of which was his headed goal in the final against West Germany.

While huge sums of money are lavished on even the most average of players in today’s game, back in ’86, many of the Argentine squad didn’t have the earning power of Maradona, Passarella or Valdano.

Maradona tells the story: “El Tata Brown was such a humble guy that, during that awful tour we did in Colombia before the cup, he had stood staring like a little boy at a Rolex watch in the duty-free shop.

‘Get it,’ I told him.

‘I can’t, Diego,’ he said.

“When we got back to the camp in Mexico, I gave him the watch. I had a gut feeling that this guy was going to give us a hand to win at the World Cup.”

Arcucci’s book is littered with little details that would have been otherwise lost in time.

The team’s accommodation, a short bus trip from the famous Azteca Stadium in Mexico City, was modest bordering on decrepit.

“The rooms were small, with exposed brick, a light bulb hanging down from the ceiling, and two cots. That’s it.”

During the tournament Maradona roomed with Lecce striker Pedro Pasculli who would later lose his place in the team to Hector Enrique – a player whom Maradona rated above most in the side.

Their pre-game routine was to wander around the nearby Perisur mall where they would visit Helen’s Ice-Cream parlour.

Before games, they would listen to Bonnie Tyler’s ‘Total Eclipse of the Heart’ and the ‘Rocky’ theme tune.

Prior to the tournament, many observers had Michel Platini ahead of Maradona in the pecking order, which seems a ridiculous assessment today.

Throughout the book, the little Argentine doesn’t mince his words and describes the Frenchman on more than one occasion as a “heartless turkey”.

And he reserves special ire for Carlos Bilardo and says the manager didn’t know what he was doing half the time.

He criticised Bilardo for their pre-tournament tour of Colombia and for his lack of knowledge of the South Korean players, Argentina’s first opponents at the World Cup.

“We didn’t even know their names, Bilardo less so.”

And while the squad landed in Mexico as probably the fittest among the 24 competitors, some players were struggling at altitude, including midfield hard man Sergio Batista who threatened to leave the camp after being substituted in the early games.

Arguably the best partnership in Mexico was Maradona and the quick-footed Jorge Burruchaga. Despite his undoubted worth to the Argentine cause, Burruchaga had his run-ins with Bilardo.

“Burruchaga was settling in nicely, but Bilardo would drive him nuts, screaming at him.

‘Tell him to quit yelling at me, Diego,’ Burru would say to me. So I went over to him and said: ‘Easy does it, Carlos, easy does it.’”

The 3-1 win over South Korea is remembered for their violent approach against the South American contenders. Maradona was fouled 11 times in the game.

Describing their tactics as “brutal”, Maradona writes: “Their number 10 brought me down at midfield, far from where the action was, and then he gave me a hand to help me up. I was feeling so good that I accepted all apologies.”

The Argentines drew 1-1 with defending world champions Italy in Puebla where Maradona was man-marked by his Napoli club-mate Salvatore Bagni.

Maradona’s equaliser – a deft flick beyond Giovanni Galli – was “one of the best goals of my life”.

The side eased to a 2-0 win over Bulgaria in their final group game which qualified them for the knock-out stages against South American rivals Uruguay.

Looking back, Maradona was mystified as to why a lot of the games in Mexico were played under a sweltering noon sun.

“Playing at noon with the altitude and the smog was downright criminal. We were beat by the end. During the last 20 minutes of play, some of the guys were reduced to walking; it was scary to see the vacant stares in their eyes.”

It is fate Maradona was in the best physical shape of his career entering Mexico. He had knee and ankle injuries that held up during the tournament.

“I was strong, really strong. I mean, if you look at the photos back then, I look like a boxer, with strong arms, pecs, a nice-looking kid. And I was fast. I would fly through the air… If we were at sea level, they might be able to catch me… The altitude ended up working in my favour.”

Maradona rates his performance in Argentina’s 1-0 win over Uruguay in the second round as the best of the tournament.

It was the first time the team had to wear their second-choice kit – navy jersey with black shorts. But there was a problem. A storm hit Puebla in the closing stages of their game against Uruguay.

But the jerseys weren’t water resistant and it weighed the Argentine players down like a “wet sweater”.

With the Malvinas/Falklands War providing the backdrop to their quarter-final with England, the team were due to wear their second-choice jerseys again.

“Playing a match at that altitude in Mexico City at noon in a sweater? No way! We asked Le Coq Sportif to make us a blue jesery eyelet, just like the home jersey but they said they couldn’t do it in time for the match. Bilardo took out a pair of scissors and started punching little holes in the blues jerseys to try to imitate the eyelet – totally ludicrous.”

Maradona assigned “poor Ruben Moschella”, an AFA office employee, to source a new set of blue jerseys.

Moschella went to 40 different stores and came back with two different blue jerseys.

“He could have just bought both sets, but that’s how they pinched pennies back then.”

Maradona chose the lighter of the two blue jerseys and two seamstresses were recruited to sew the national team emblem and numbers on them. Problem solved.

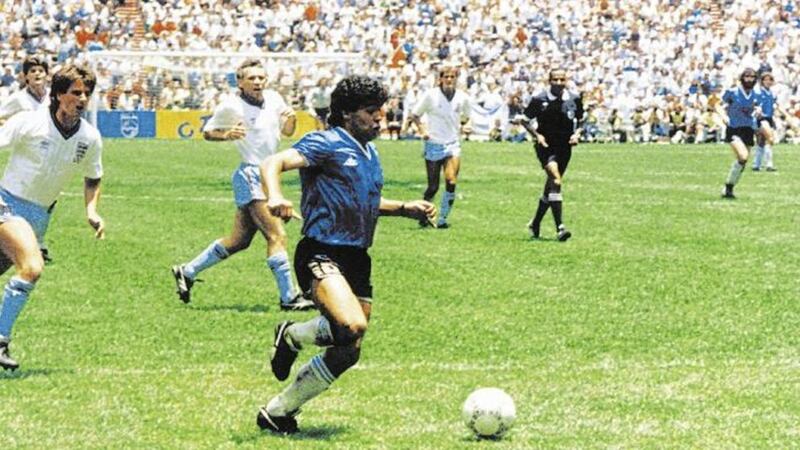

With dodgy blue jerseys, Argentina went to the Azteca to face England, and the rest is history.

Maradona’s two goals that afternoon are the most talked about in the history of the game.

When he rose above Peter Shilton and punched the ball to the net, Maradona wheeled away and encouraged his team-mates to celebrate with him before the officials could have second thoughts and rule the goal out.

“I wanted the others to come over, but only Valdano and Burruchaga did. The thing is, Bilardo didn’t let the midfielders celebrate the goals because he didn’t want them to get tired out. But this time I needed them – I really did.”

With the English still reeling, Maradona embarked on a run that left football in awe of his talent. He blamed Shilton for not standing up to him better as he “faked him” to slide the ball into the English net.

England’s nobility, Maradona suggests, is why that second, unforgettable goal was possible.

“If we had been playing against another team, I would never, ever have made that goal,” Maradona writes. “Another team would have knocked me to the ground way earlier, but the English are noble people.”

Two more moments of Maradona’s genius saw off semi-final gate-crashers Belgium before Argentina faced the physically imposing West Germans in the final.

Full-back Hans-Peter Briegel was the epitome of Germany’s physical prowess.

“Breigel,” Maradona recalls, “was a body-builder who ran triathlons and God knows what else. His veins were like sausages and his calves were as wide as my chest.”

Although he was man-marked in the final by a young Lothar Matthaus, Maradona exerted enough influence and had a hand in all of Argentina’s three goals.

Despite a late fight-back from West Germany, Burruchaga raced onto Maradona’s through pass to clinch a 3-2 win in dramatic circumstances.

Maradona spoke with German goalkeeper Harald Schumacher in the anti-doping station afterwards and said: ‘Good thing you won 3-2, because if it had gone to over-time you would have scored five. We couldn’t go on playing. Our defenders were shot.’

I loved this book. I loved its nostalgia and even the rough edges.

As a kid, the summer of 1986 was a fairytale.

Diego Maradona was a fairytale, almost too good to be true.

He was better than a child’s dreams.

I loved re-enacting his goals, his dribbles, the commentary and the whole drama of what he single-handedly created, and what we still cherish, in Mexico 31 years later.

I miss that summer more than any other.

Maybe I just miss my youth and the imagination Maradona ignited in all of us.

‘Touched by God: How We Won the Mexico ’86 World Cup’ – Diego Maradona and Daniel Arcucci, Penguin Random House LLC, 2017, £20.