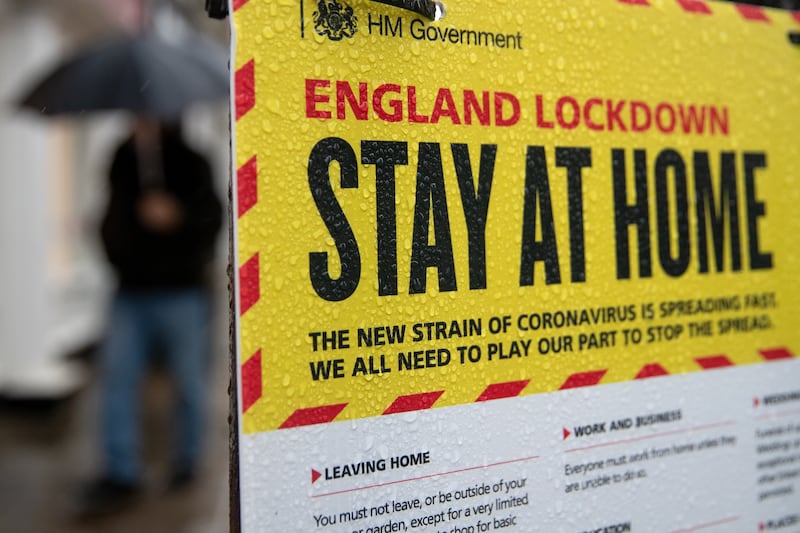

THE emergency budget the assembly passed this Tuesday shows how coronavirus has telescoped all Stormont's long-term financial issues into an imminent crunch.

Despite over £1 billion in extra funding from the Treasury, the Executive will have burned through 80 per cent of this year's money by the end of October, with five months still to run on the financial year.

Then what?

"Is it a case of spend now and ask questions later?" fretted Green Party MLA Rachel Woods.

When the Greens worry about fiscal rectitude, we are approaching the End of Days.

During the budget debate, assembly members presumed the Treasury will bail Northern Ireland out beyond October as part of its UK-wide recovery plans.

However, few sounded comfortable with this as a short- or long-term solution.

"I worry that we continue under the promise of jam tomorrow," said Alliance's Andrew Muir.

The DUP's Mervyn Storey, while observing we are all UK taxpayers, said we are not paying enough to cover spending, which he ominously termed "the law of first principles".

The UUP's Mike Nesbitt cited prime minister Harold Wilson's infamous 1974 "spongers" speech and urged that any extra funding be put towards making Northern Ireland "more self-sufficient".

One exception was the SDLP's Matthew O'Toole, who noted it has never been cheaper for the government to borrow.

There has been a fascinating shift among economists and policy-makers around the world towards once-exotic theories about running massive deficits, even printing money to do so, without worrying about inflation, interest rates or currency values.

It is an argument above Stormont's pay grade but that has rarely stopped it arguing before.

As the theoretical opposite to austerity, Sinn Féin finance minister Conor Murphy might have been expected to join O'Toole in calling for a Treasury splurge.

Instead, he said: "I completely agree with Mike Nesbitt about a prosperity agenda as opposed to a dependency culture."

Murphy made this his concluding remark in the debate, adding that Northern Ireland's subvention is "the gap we have to close, and I would prefer we closed that gap through our own efforts".

While not technically a change in Sinn Féin's policy, the change in tone was striking.

Admittedly, Sound Money Murphy had no specifics on closing the gap, beyond painless promises of investing for growth.

He was not keen on Stormont using its own borrowing powers, as "this does not come without a cost attached".

Nor was he keen on raising taxes. Challenged by People Before Profit's Gerry Carroll to target "rich corporations and the wealthy", Murphy said: "We do not have the sort of taxation powers that he berates us for not using."

In fact, Stormont has the option to raise corporation tax, although the power was negotiated to lower it. One of Murphy's first acts in office was to rule that power out.

Stormont can use the rates as a wealth tax on property and has the power to extend this to non-agricultural land, all of it under the finance minister's remit. Domestic rates have been frozen this year.

Murphy did not mention cuts, which are a neuralgic issue for his party. Sinn Féin has occasionally and reluctantly gone along with cuts in the past but never while holding the purse strings.

Murphy is only his party's second finance minister, the first to pass a budget and he has always had more cash to spend, first from the New Decade, New Approach deal and then due to the epidemic.

Without accepting the inevitability of major cuts, taxes or borrowing, claims of self-sufficiency are ridiculous.

Yet the budget debate was not ridiculous: Murphy refrained from grandstanding and finger-pointing, as did most assembly members. Everyone acknowledged the reckoning is coming.

When the SDLP's Sinead McLaughlin said "the old ways of divvying up the money between the two largest parties have returned", Murphy replied that only one minister - and not the SDLP's lone minister - had objected to any budget allocation during executive discussions.

The budget passed in the assembly with only one vote against, from Carroll.

Far lesser financial strains than Stormont currently faces were long seen as fatal to devolution.

Under Tony Blair they were avoided at any price. When Stormont had to budget for welfare reform, it hovered on the brink of collapse for three years.

Now it appears the Executive parties want to continue their coronavirus truce when October's bill arrives.

Given the size of the bill, that intent is worth something.