On Thursday night, a small campaign started by a Dutch yoga teacher living in London spread across the country.

People in streets across the north and Britain, including Downing Street, stood on their doorsteps and clapped and cheered for NHS staff working on the frontline of the coronavirus pandemic.

The campaign wasn’t government-led. It was an idea from one 36-year-old immigrant which went viral.

While many NHS workers tweeted and spoke of their appreciation for the gesture, one Bath-based doctor was a respectful dissenting voice.

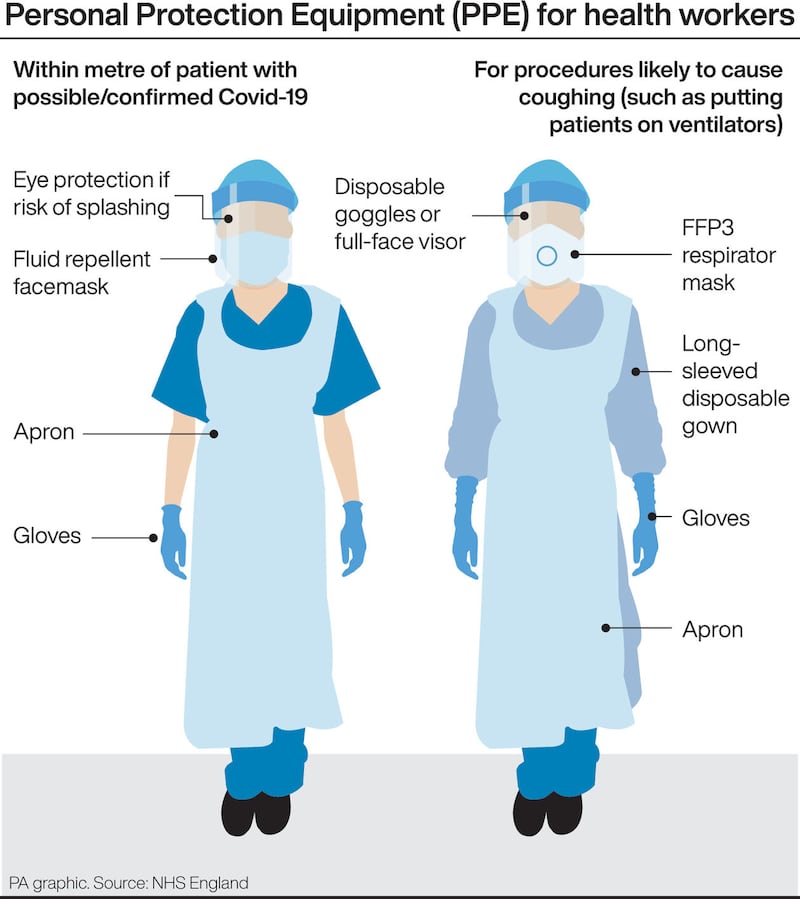

He tweeted: “I mean, we’re grateful and everything, but I’d prefer a mask that’s not 4 years out of date and something other than a flimsy plastic apron when I’m assessing my patients tbh (to be honest).”

The sight of Boris Johnson clapping for NHS workers on Thursday night was extraordinary, given he has long been part of a government wedded to austerity and a history of cutting public services to the bone.

His involvement showed the incredible lack of self-awareness which has characterised his entire political career. No doubt his inability to launch a clear information campaign at the start of the outbreak led to general confusion about how people could reduce their risk of catching the highly-contagious virus.

Time will tell if swifter action could have reduced the overall number of cases. What is obvious is this pandemic still hasn’t reached its peak.

Last week’s public show of appreciation, no matter how well-meaning, is not a substitute for practical support for health workers who spent years fighting for every small salary increase and are now on the frontline, many with insufficient protective equipment.

Consultant surgeon Amged El-Hawrani (55), who died on Saturday evening, became the first frontline NHS hospital worker to die after testing positive for coronavirus.

The day before, a nurse in the Republic became the first healthcare worker in the state to die from the virus.

Care staff who work in our publicly-owned and private nursing homes are also at high risk.

Some staff, whose essential work was branded as ‘low-skilled’ by the government’s new immigration policy, are being advised to self-isolate at their place of work if they test positive for coronavirus, leaving them with huge childcare and financial challenges.

Staff across health and social care have been united in their call for proper personal protective equipment.

One A&E nurse told the BBC’s Nolan Show on Radio Ulster that she is treating coronavirus patients with a "knot in her stomach" amid fears of infection.

As The Irish News’s health correspondent Seanin Graham revealed last week, fearful frontline nurses have sought legal advice about treating Covid-19 patients without proper masks and protective clothing.

For too long we have taken care and health workers for granted, dismissing their work and the risks involved.

In a way it’s a typical human flaw not to appreciate what we’ve always had.

In his poem Those Winter Sundays, Robert Hayden writes about his father lighting fires in their home every morning, even on Sunday. As an adult, he understands that he didn’t appreciate his father’s practical demonstration of love, saying he spoke “indifferently to him,/ who had driven out the cold/and polished my good shoes as well.”

The sonnet’s final lines always hit me square in the chest: “What did I know, what did I know/ of love’s austere and lonely offices?”

What do most of us really know about the labour it takes to care for the ill and elderly in hospitals and care homes? Taking blood samples, giving medication, checking charts, carrying out bed baths and enquiring about bowel movements is hardly the stuff of glamour. The emotional toll of caring for seriously ill patients must be immense, the consequences long-lasting.

The daily care shown in hospitals and other care settings is a form of spiritual office. Speaking from experience, most nursing care goes way beyond the physical and into a deep understanding of the patient as a human being.

Yet we take good care, free at the point of entry, as a given.

Good wishes won’t save us. Our health and care workers carrying out their daily offices need protective equipment. And they need it now.