Our lives lead us to places that we can, in truth, never really imagine at the start of each new pathway. And our retrospective memories of those journeys often impose an artificial sense of order where no roadmap existed in real time.

In that vein, I found myself last week digging out old photographic negatives of Antrim’s last appearance in an all-Ireland hurling final, playing against Tipperary in Croke Park 30 years ago. I had taken the photographs as a 16-year old, attending the match with our wider family circle.

So, as a small pebble of positivity in the negative ocean of social media, I posted my album of memory on Twitter.

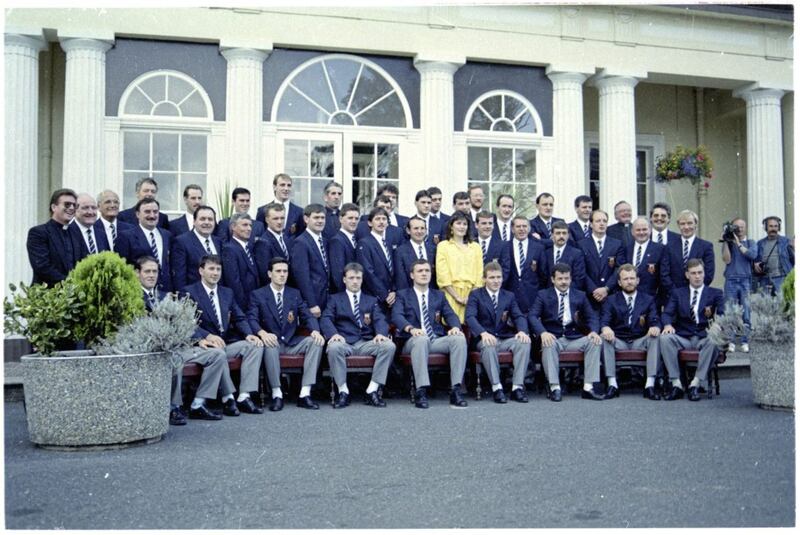

My images capture the nervous optimism of smart young jackets on that bright Sunday morning in September 1989 right through to the sweat-soaked reality of defeat around 5 o’clock that evening as the late Cardinal O’Fiach and other famous (some infamous) faces watched on, in the old Croke Park with its rickety benches and draughty stands.

Yet here’s the thing: despite their unvarnished authenticity, my photographs of Antrim’s landmark battle with Tipperary in the 1989 final are all edited, partial, incomplete, blinkered, selective – just like my memories. I only have angles of snapshots and moments from my singular point of view, mere split-seconds of fading colour that miss out on vast lifetimes of context. Tens of thousands of alternative memories exist from that day, held by people all over Ireland.

One single day; one single match; three decades ago. And the only objective, indisputable fact that is the final scoreline. Everything else from that day – every picture, every conversation, every encounter, every clash, every smell, every shout - is just a tiny little tile trying to slot into a vast mosaic of history that can never actually be completed.

Because the old Croke Park has disappeared. Because there is no longer that rump of uneven turf across the 21-yard line in front of Hill 16. Because some legends who were in the thick of it have already sadly passed on. Because even hurling sticks have been altered in their size and shape and quality. Because unseen photographs, forgotten programmes and untold anecdotes suddenly emerge 30 years later. But most of all, because that day is gone. Pure and simple.

Which leaves us not with a finely composed mosaic of well-framed history but rather with a beautifully washed watercolour of collective memory, where one person’s story seeps into another person’s consciousness and awakens an alternative recollection about the same social experience. This is the real potency of memory.

It’s an important wider point for our society’s approach to the organisation of memory and remembrance about past conflict - individual incidents and destructive patterns of ordered chaos that stretched around 40 years, over 14,000 single days.

One lesson is that when we respectfully share our respective memories, we have the opportunity to experience the gift of learning new things about old stories from different perspectives. But if we’re not listening to others, then we’re merely lecturing them.

Going back to my photographs, within a few days they’d been seen nearly 60,000 times on Twitter and the circle of reaction was universally upbeat and positive – countless individual watercolours powerfully blending together to paint a collective canvas of social memory from 1989.

The legendary snapper John ‘Curly’ McIlwaine even asked if I’d taken up the wrong career, a tremendous compliment for pictures that I’d made as a 16-year old kid – never remotely foreseeing their value 30 years later, on my own meandering journey.

It may be a small lesson, but it all makes me wonder whether our memories (and our truths) are often affected by our motivations. In life we frequently cannot choose ‘what’ we remember, but we can always choose ‘how’ and ‘why’ we are remembering – choosing what motivates us in our recordings, our rationales and our relationships.

If we worked a bit harder at positively improving our own motivations, then we might also improve our shared canvas of memory across this society. People are increasingly hungry for public positivity and for better ways of engaging with others, going forward. Learning from our memories, as we listen to others, can be worthwhile art.