LAST week women effectively stopped getting paid until the end of the year. Not good news in the run-up to Christmas.

Before female readers of this column fling down the august publication and rush post haste to their banks, it’s worth pointing out this is a notional calculation by the Fawcett Society based on the fact that in 2016 the gender pay gap still sits at 13.9 per cent.

In fact, if you are a woman the chances are you have been paid almost a sixth less than most men.

That amount is eloquently illustrated by Equal Pay Day on November 10, which supposes that up until that date women and men take home the same salary, but in order to `readjust’ to ensure their annual pay cheque reflects the true reality of the situation, women abruptly stop being paid anything for the rest of the year.

It seems scarcely conceivable that this can be the situation 46 years after the Equal Pay Act made less favourable treatment between men and women illegal.

However, even more alarming is the projection that it will take 60 years to achieve wage parity at the latest rate of progress.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission warn “we simply cannot ignore the scale of the disadvantages that working women face… (as) girls and women outperform men at every stage in education, but time after time this success is not translated into rewards at work.”

While the jobs women do are more likely to be low-paid, they are also less likely to receive a bonus or progress to the highest position in their organisation.

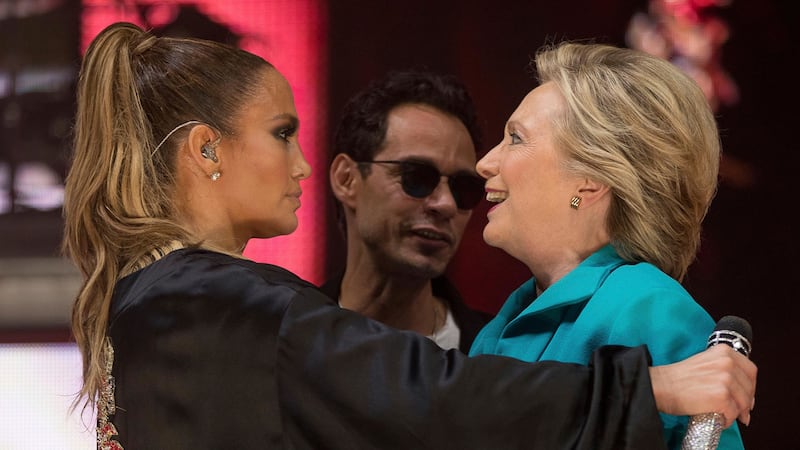

Many people would point to the results, two days earlier, of arguably the biggest and most public job application of them all as proof that something is rotten at the heart of society.

By all accepted criteria Hillary Clinton was eminently more qualified to become 45th president of the United States than billionaire businessman Donald Trump.

In this case, she wasn’t even doing that thing that women are notorious for and `hiding her light under a bushel’.

“I think Donald just criticised me for preparing for this debate. And yes I did. You know what else I did? I prepared to be president,” she told America.

A majority chose her over him, but, due to the electoral college system, she still failed to “shatter that highest and hardest glass ceiling” – like Donald Trump’s wife Melania, borrowing shamelessly a quote from Barack Obama’s wife Michelle.

I mention these women in reference to their spouses advisedly, because it occurred to me, in the midst of the international disappointment and soul-searching, that this should not necessarily have been Hillary Clinton’s election.

I’m not suggesting she should have won her last bid for the nomination, instead of Barack Obama, when arguably America was already weary of the by then tarnished Clinton brand.

Instead, consider this: Hillary Rodham graduated from prestigious Yale Law School in 1973 – a year before Bill Clinton from the same Ivy League college.

Two bright and able students graduate from a top university a year apart and both enter their chosen profession (in this case an amalgam of law and politics).

Forty years later, which would you expect to have “progressed to the highest position in their organisation”?

I’m actually not suggesting that the answer should automatically be the earlier graduate – in an ideal meritocratic world the best person for the job could be either.

But you wouldn’t have thought a serial adulterer with a habit for attracting scandal would be that person, over the one who was hard-working, focused and endlessly expanding her knowledge.

But then the latter was the woman.

Within a few short years of graduating, she was already modifying herself to aid her husband’s political career. He was to make the first attempt on the presidency and afterwards he would `support’ hers (See also, allegedly, Cherie Booth, who with her first class degree was seen as a higher flyer than Tony Blair).

We now know that her turn as president would never come.

Four decades should be enough time to change the world. Why haven’t we?

@BimpeIN