In mid-November 1983 I was an idle 18-year-old living in the vain hope that drumming in a heavy metal band – along with occasional vocals – would enable me to escape Downpatrick and avoid anything approximating real work for the rest of my life.

Liverpool were top of Division One, while Leicester City languished in 21st place; Billy Joel’s Uptown Girl was No 1 in the charts, and weeks before Neil Kinnock had replaced Michael Foot as leader of the British Labour Party.

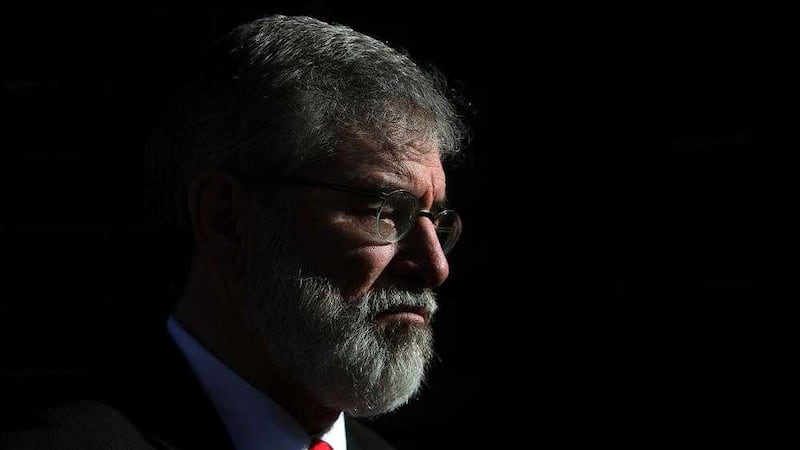

It was at this time that Gerry Adams assumed the Sinn Féin presidency – a position he has held unbroken for the past 33 years. His party colleague and new Stormont infrastructure minister Chris Hazzard hadn’t even been born when the then West Belfast MP succeeded Ruairí Ó Brádaigh.

Giving greater voice to a hitherto latent element within the Republican Movement, the Sinn Féin leader set a course that over the following decade would see the coupling of the IRA’s campaign of violence with an effective political machine. The military discipline of a revolutionary organisation applied to both wings of the movement. While ostensibly democratic, decisions about political positions and direction emanated from the IRA Army Council.

It’s difficult to say where the seeds of the peace process were first sown, but it’s widely acknowledged that Gerry Adams was central to the development of the strategy that would bring an end to armed struggle and ultimately see Sinn Féin join the DUP in a power-sharing government at Stormont. More recently, the party has also made notable advances in the Republic, where following February’s Dáil election it has 23 TDs.

The movement’s ultimate goal of uniting Ireland is thus far unrealised but for a Ballymurphy man who recently cast himself among the world’s most disenfranchised, Gerry Adams should be reasonably satisfied with what he would regard as a positive contribution to Irish politics.

But to some, the man mainstream republicans regard with messianic-like zeal has become an electoral liability, especially in the south where Sinn Féin sees its greatest potential for growth. Publicly the party rejects this notion, blaming any indications of poor support for its leader on negative coverage in the Denis O’Brien-owned press. There is some justification for this but it doesn’t tell the whole story. The 67-year-old Adams’s lust for power may not have diminished but his poor grasp of the south’s income tax system and gaffes about the special criminal court during the election campaign demonstrated that he is perhaps not as astute as he once was.

While this blunt assessment of Adams’s current credentials has been widely aired outside of the party, it was not until recent days that somebody within Sinn Féin broke ranks and publicly criticised the leader. It’s likely to be some time before we know if Co Cavan-based Thomas McNulty’s unprecedented outspokenness is an orchestrated kite-flying exercise ahead of an attempted leadership challenge, or if he is merely a lone voice that will soon fall silent. The former IRA prisoner, who originally hails from Dungannon, is the chair of a Sinn Féin cumann and has the necessary pedigree for the comments to carry weight. So far the best Sinn Féin can offer to discredit him is that his 2013 memoir 'Exiled' has a lot of spelling mistakes.

While by no means as significant as McNulty's remarks, former Belfast councillor and now Dublin Mid-West TD Eoin Ó Broin this week spoke of a change of leadership in five years' time. So whereas a week ago nobody in Sinn Féin had dared mention succession, the genie is now out of the bottle.

How the debate around a new leader is conducted will provide an illustration of how Sinn Féin sees itself in the years ahead. Will it be an open, transparent contest or something more akin to a decree that reflects a continued adherence to the movement's old structures? The electorate in the south will watch with interest.

The received wisdom is that Gerry Adams and his team will obstinately hold on to the leadership and that he will lead Sinn Féin into the Republic’s next general election, which could be anything between six months and two years away.

This may indeed be what the majority of party members want, but like Tommy McNulty there are some who believe that every day Gerry Adams stays on signals further damage to the Sinn Féin project.