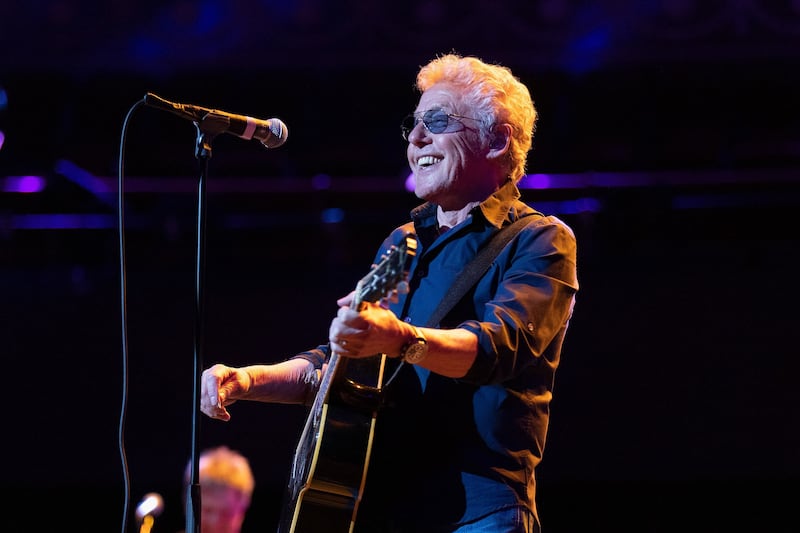

HE USED to boast long, wild, corkscrew curls but today Roger Daltrey's short grey hair is more conservative than chaotic – though with his black T-shirt and jeans combo, and sunglasses with smoky blue lenses (which he wears indoors), there's still an air of ageing rock star about him.

At 74, The Who's lead singer looks a decade younger than his age. He was the relatively clean-living frontman of the band, known for his stage presence and energy, while his drug and alcohol-fuelled bandmates Pete Townshend, John Entwistle and Keith Moon frequently got wasted in the 60s and 70s.

Meeting Daltrey, the working-class Shepherd's Bush-boy-made-good is still a bundle of energy, standing up when he could sit down, animated, full of ideas and opinions, refreshingly devoid of filters in his responses.

But then he was the band member whose brain was never addled by long-term cocaine use or week-long benders.

He wasn't the one who drove a Cadillac into a hotel swimming pool (that was Moon) or smashed up instruments (Townshend and Moon), or demolished hotel rooms to such an extent that the band was banned from many during their heyday.

"Somebody had to be the sensible one," he says now. "I was the straight one with three addicts in the band. I could have very easily gone off the rails too but the most important thing in my life was to be a singer. I knew I had a sound in me which could move people."

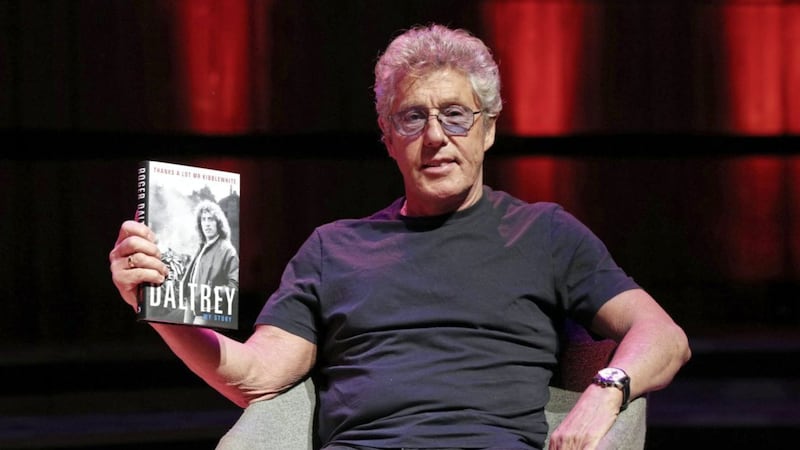

He details all the excesses – from the high points of hits including My Generation and rock operas Tommy and Quadrophenia, to the lows, notably the deaths of Moon and Entwistle – in his memoir, Thanks A Lot Mr Kibblewhite: My Story (named after his old grammar school teacher who said he'd never amount to anything).

Off stage, Daltrey would distance himself from his drug-ravaged bandmates, he recalls.

"In the 70s, quite often I'd stay in different hotels because we got thrown out of so many. We used to do three-hour shows at enormous volume. So if you didn't sleep that night and you had a show the next day, your voice wouldn't recover for the next show. The last thing I wanted to do was to let the audience down."

He may not have been a drug addict, but he was a sex symbol. He had left his first wife Jackie and their son Simon to pursue a rock career, and when he married American model Heather in 1971, she knew the score, he says.

"If it was going to last, it had to be a marriage with no issues because of the business I was in," he writes. "Life on the road, month after month, can be a very lonely place without company. And we were away on tour for five, six months at a time as one of the biggest rock bands in the world."

He admits that to come home and tell her he'd been a good boy would have been a lie.

"Sexual infidelity should never be a reason for divorce," he writes. "For a man, it's mostly just a s**g, unless you fall in love."

He and Heather, with whom he has three children, have been together for nearly 50 years.

"I'm starting to like her and I'm thinking of not kicking her out," he says, laughing out loud. "I worship her. We are closer now than ever. She understood me and knew the business I was in, and accepted me for my honesty at the beginning, and it worked. We never let those silly things that usually break marriages up break ours up.

"She accepted it [his infidelities] because she knew the business. To have any kind of long-term relationship, you need to accept that that's part of your life, as long as it doesn't crush the marriage."

He says he told her about the other women in the early days. But was she faithful?

"I don't know, I hope so. If she wasn't, then what's good for the goose is good for the gander."

So, at what point did the marriage become monogamous?

"You just grow out of it," he says with a shrug. "I'm an old man now. Grandkids [he has 15] come along, and you're suddenly looking through the right end of the telescope of life and it all makes sense."

In 1971 he and Heather moved to Holmshurst Manor, a country pile in East Sussex, which was used for a few years as the ultimate hippy crash pad. There were parties, but there was also peace and quiet.

"It was something I needed to do. I became trapped in London. There were always girls sitting on the front wall. I couldn't take it. I was only 30 miles from London but we might as well have been in the Sahara Desert, and I learned the value of community again, which I'd had in Shepherd's Bush."

He still lives in the wilds of East Sussex, with its immense views and big skies. He goes trout fishing and builds dry-stone walls, an antidote to the madness of performing in front of legions of screaming fans at Woodstock, Glastonbury, the Hollywood Bowl and Madison Square Garden over the years.

He has had other children out of wedlock, although he's vague as to exactly how many.

"I can't pretend that my relationship with my children that turned up when I was 50 is the same as it is with the children that I brought up and changed their nappies," he says today.

Away from family life, the years of of rock have taken their toll on his health. After collapsing on stage in Florida in 2007, doctors discovered that at some point in his career he'd broken his back, which he thinks might be when he fell badly doing a somersault, while filming I'm Free on the set of Tommy in 1974.

He's suffered serious concussions thanks to microphone stands ramming his face, wears hearing aids to counteract the deafness, and has suffered depression.

Three years ago, the second half of The Who's 50th anniversary stadium tour had to be postponed after he suffered a horrific strain of viral meningitis.

"I don't recommend that one," he says now. "I was quite ready to go. I learned not to fear death. I lay there on my last knockings. They didn't really know what was wrong with me. I'd been given all kinds of tests. I was going barmy because the lining of the brain swells up and it drives you crazy.

"I had a physiotherapist I used to take on the road to keep me in shape, and when I was feeling stiff or there was a knot in my back, she used to say, 'Let go of it, what are you hanging on to it for?'

"When I was in hospital those words came into my head, 'What are you hanging on for? Let go'. And I felt an incredible peace came over me.

"We think about death as an exit, but if you turn it around it becomes an entrance. So I head for the entrance now. I feel I'm ready to accept it at any time now."

Yet he's still hungry for life and we haven't seen the end of The Who, he says.

"It's not over. We are on our last farewell tour and we always said it's the beginning of the long goodbye," says Daltrey. "But how long that goodbye is, we don't know..."

:: Thanks A Lot Mr Kibblewhite: My Story by Roger Daltrey is published by Blink, priced £20.