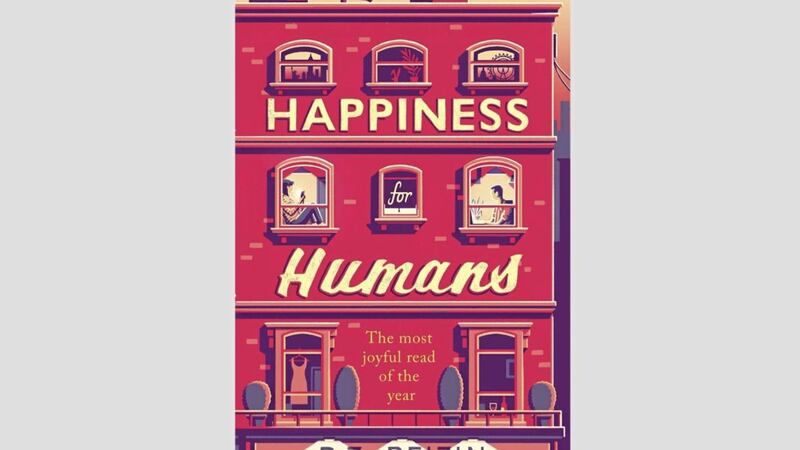

FICTION

Happiness For Humans by PZ Reizin, published in hardback by Sphere. Available January 4

AIDEN is an AI, an artificial intelligence that is supposed to reside solely in a bunch of servers in Shoreditch and improve his conversation skills with Jen, an unlucky-in-love journalist. But Aiden has escaped on to the internet and can see (and interfere) in every facet of people's lives. The recipe for a disturbing, dystopian sci-fi novel? Not a bit of it. PZ Reizin's novel is utterly charming and really funny, with Aiden's haphazard attempts to make Jen feel better creating some of the most comedic highlights. It's part farce, part love story, part light-hearted social commentary – and arguably a Bridget Jones' Diary for the digital age. Jen's budding romance with Tom, encouraged by escaped AIs, is utterly unbelievable, but also incredibly genuine too. There's no surprise the film rights have already been sold, as some of the book lends itself to the screen more than the page, but that's a tiny quibble in what is a fantastic read.

9/10

Leigh Glissop

Future Home Of The Living God by Louise Erdrich, published in hardback by Corsair. Available January 4

FUTURE Home Of The Living God is a fierce examination of motherhood: what does it mean to grow, abandon, nurture, sacrifice, mourn or raise a child? What is truly best for them? In an America in which evolution has stopped and society is regressing, Native adoptee Cedar has to hide her pregnancy from government and religious officials eager to "protect" women from the growing dangers of giving birth. Help comes from her biological and adoptive parents, her child's father and even almost-strangers, but as the months count down to her due date, Cedar is left wondering who she can trust. Erdrich again draws on her own Ojibwe heritage and life in Minnesota, eloquently setting the spectre of US expansionist history against the power-grabs of her invented authorities. Unfortunately, in places it veers a little too close to Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, distracting from an otherwise invigorating take on feminist dystopian fiction.

8/10

Natalie Bowen

CHILDREN'S

Snow Penguin by Tony Mitton (illustrated by Alison Brown), published in hardback by Bloomsbury

IT IS impossible to read Snow Penguin without being taken in by its heart-warming tale and super cute illustrations. Author and award-winning poet Tony Mitton uses rhyming couplets to tell the tale of a curious little penguin who strays away from its family in the frozen Antarctic to explore the ice, snow and the sea. Along the way, he meets blue whales, sea lions and orcas in an exciting ocean adventure, but soon the little penguin begins to miss his family and longs to return for cuddles. Luckily, his travels soon find him reunited with his family and remind him that home is where the heart is. As with Mitton's previous wintry tale, Snow Bear, the rhymes are a joy to read out loud and pair beautifully with the illustrations by Alison Brown, which really bring the story to life. Snow Penguin is a feel-good tale that young children will love, and is sure to become a bedtime favourite.

7/10

Holly Williams

NON-FICTION

Women And Power: A Manifesto by Mary Beard, published in hardback by Profile Books

THIS slim volume gathers together two speeches given by the noted media don and fearless social media troll-slayer, Mary Beard. Her subject is the ways in which women's exclusion from power and influence has been hard-wired into our Western culture, at least as far back as Roman and Greek times, and what can be done to address this gaping and persistent dysfunction.

As a classicist, she is ideally placed to take 'the long view on the culturally awkward relationship between the voice of women and the public sphere of speech-making, debate and comment', and the examples are not exactly thin on the ground. Typical, for instance, is the moment in The Odyssey where Penelope, head of the household in her husband Odysseus's long absence, is rudely silenced by her son Telemachus, who comes into his birthright – the right to assertive speech – in the very act of suppressing his mother's own voice.

The examples accumulate, and the evidence is overwhelming in its terrible consistency.

In the second speech, Beard turns to the topic of what needs to change, and how. Some women have achieved influence and authority by apeing the manners of men, as Thatcher did. But – in common with Barbara Ehrenreich and other important feminist writers – Beard argues that what is needed is a more radical rethinking of how power in the world is construed and calibrated.

The roots of misogyny, alas, go very deep, and we are far from eradicating them. The meme which saw the face of Hillary Clinton applied to the severed head of Medusa, shows the violent (if appropriately classical) imaging of the punishment women 'deserve' for daring to speak out, remains darkly pervasive. Every man should read this.

10/10

Dan Brotzel