While the level of support for the DUP will not be clear until after the election, it appears that the party (and indeed unionism in general) may struggle to retain votes.

A century after the state was founded specifically to give them an artificial electoral majority, unionists appear to have squandered what should have been perpetual political power.

So where did it all go wrong for them, do they understand how it happened and what are their prospects for recovery?

It is commonly argued that unionism’s problems began with Brexit, but the explanation lies much deeper in history. The beliefs and behaviour of modern unionism have been shaped and ultimately blighted by what we might call the three Ps: the plantation, partition and Paisley.

The Ulster Plantation’s theft of land was more broadly aimed at suppressing the indigenous population, their laws, language and traditions. While that was normal in the 17th century, unionism progressed little beyond that stage.

In 1969, Prime Minister Terence O’Neill said that if you treat Catholics with consideration and kindness, “they will live like Protestants”. This suggests that at least some unionists wanted union not with contemporary Britain, but with medieval England.

Cultural suppression was not challenged until the Gaelic revival of the late 19th century, when most of Ireland rejected colonialism, in all areas from language to sport. At the turn of the last century, for example, cricket was still the dominant sport in Kilkenny. (Although at the same time they were playing hurling in Newry.)

Unionism had killed the radical tradition of Presbyterianism, which fuelled the revolutionary ideas of the 1798 rebellion. Later, partition destroyed unionism’s need to modernise, by being gifted an artificial state in which to indulge cultural and political repression. It criminalised free speech, outlawed political beliefs and denied even the concept of debate. Partition became unionism’s path to self destruction.

By 1938 a woman here was more likely to die during childbirth than when the state was founded in 1922. Despite that, in 1947 the Ulster Unionist Council condemned the proposed introduction of the NHS as “ingested socialist legislation”.

Unionism got its chance with the civil rights movement in the 1960s. A mature political party would have observed a changing world, gone along with it and claimed credit for reforming the state. Instead armed unionism batoned those Protestants and Catholics seeking the right to vote in local elections.

They told us we were British, but denied us British rights. It was a major mistake.

Unionists proclaimed a cultural affinity with Britain, even though there is no specifically British culture. There are wonderful English, Welsh and Scottish cultures, but no British culture. My area of south Down, for example, was colonised by the Welsh, but I have never heard a unionist identify with the Welsh language, music or literature.

So unionists classified the Twelfth as British, even though British reaction ranges from disinterest to abhorrence at its sectarian association. The claimed religious affiliation with English Protestantism has also disappeared. Only one per cent of British young people today identify with the Church of England and 52 per cent of people say they belong to no religion.

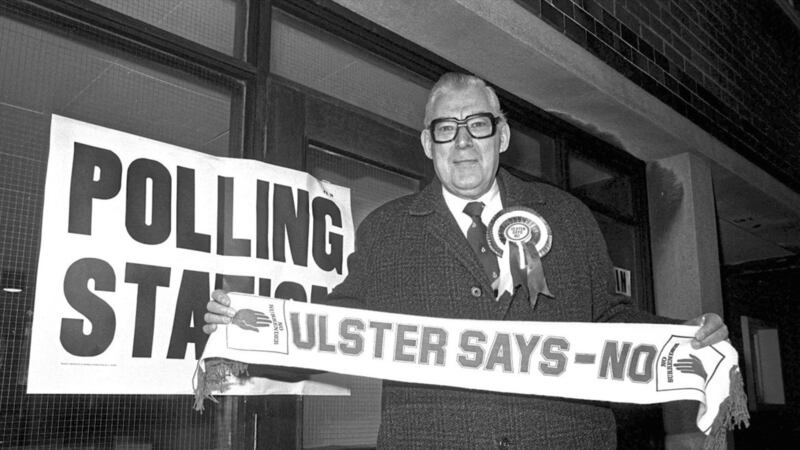

Unionism’s weakness was that while it knew what it was against, it never defined what it was for. Into that definition vacuum marched Ian Paisley, who presented unionism in terms of religious dogma and political intransigence, using not just the imagery, but the language of medieval England. If the civil rights movement damaged unionism, Paisley killed it.

As with all monopolies, unionism had grown politically arrogant, fat and lazy, failing to develop the political thinking to adapt to a changed world. There was no counter-definition, so Paisley became the health check of unionism’s purity, in his Mise Ulaidh (I am Ulster) incarnation. When he betrayed all he said he stood for, unionism had to seek a new definition. In the post-Paisley confusion, it has so far failed to find one.

It has less than five weeks to do so.