WE tend to assume that heads of government, having put so much effort into getting to the top, are generally happy in their work. Not so, in the case of Tony Blair. In a BBC Radio 4 programme last Friday, he said: “I don’t think I did enjoy the job, because the responsibility is so huge.”

It was part of an interview for a documentary series called The Prime Minister at 300 (Sir Robert Walpole was the first person to take up the position in 1721.) Blair continues: “Every day you’re taking decisions and every day you’re under massive scrutiny, as is your family.”

I was myself an eye-witness to an event in Belfast on October 13, 1997 where he came in for ferocious taunting and abuse. Earlier in the day he had shaken hands with Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness and this was followed by a visit to Connswater shopping centre in east Belfast at the invitation of Peter Robinson MP. Blair was pursued by a crowd of mainly-elderly protesters who shouted “traitor” and “scum”, had clothes pegs on their their noses and told him: “You stink!” Some of them had brought rubber gloves so that, if they got to shake hands with him, they would be making the point that he was contaminated by Sinn Féin. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (remember them?) ensured the protesters never got that close, so the gloves were thrown at him instead.

There were better days to come and, in his 2010 autobiography entitled A Journey, Blair tells us that when the Good Friday Agreement was concluded, six months later, “it was one of the few times in the job I can honestly say I felt content, fulfilled and proud”. And he adds: “There weren’t many more!”

How time flies: it is exactly 23 years today since Blair arrived at Hillsborough Castle and, having declared that it wasn’t a day for soundbites, went on to deliver a classic of that particular genre when he said: “I feel the hand of history upon our shoulder”.

Prior to writing this column, I re-read a chapter headed ‘The Long Good Friday’ in my book The Far Side of Revenge: Making Peace in Northern Ireland. One of the striking features of the negotiations at the time was the prominence given to the proposed establishment of cross-border bodies to implement a range of agreed strategies for north-south cooperation.

Unionists were very concerned that these institutions could open the door to a single all-island state. The Irish government meanwhile had drawn up a list of over 60 “subject areas” from which to choose.

In the end, six bodies emerged, overseen by the North-South Ministerial Council and dealing with such matters as trade development, inland waterways, food safety and languages. I have never seen Martin McGuinness looking so angry as details of the modified plan were finalised the following December at Stormont. Given how controversial the issue was then, it is remarkable how little attention it receives in mainstream politics nowadays.

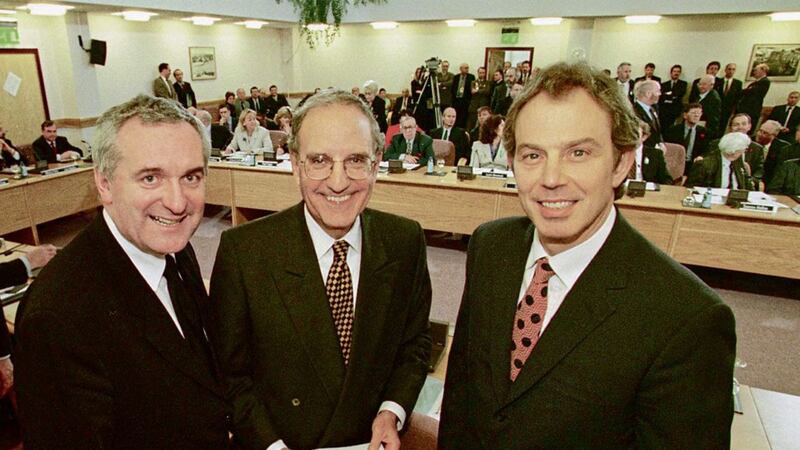

Blair and his Irish counterpart Bertie Ahern did such a remarkable job in knocking heads together to finalise the deal that perhaps they should have been added to the list of Nobel Peace Prize recipients along with John Hume and David Trimble (and some would say Gerry Adams, with Mo Mowlam and Bill Clinton for good measure) Mind you, the subsequent involvement of the British government under Blair in the Iraq War would have precipitated demands for him to give back the Peace Prize medal. What a pity he didn’t follow the example of another Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson, who kept clear of the Vietnam conflict.

One aspect of the agreement that still seems regrettable was the failure to facilitate representation in the Stormont Assembly on a long-term basis by the Women’s Coalition and the loyalist parties. Both of them had made a significant contribution to the process and it is a pity the “top-up” system used in the 1996 Northern Ireland Forum election was not retained, whereby two extra seats were allocated to each of the top ten parties in overall voting terms. If that was the case at present, loyalist discontent with the post-Brexit protocol and other matters might be expressed in a different way from the street protests and clashes with the police we have seen recently.

Email: Ddebre1@aol.com; Twitter: @DdeBreadun