One of my first published endeavours, as a teenager writing for my school’s magazine, was an interview with a UUP councillor and school governor who was campaigning for the removal of certain items from the English syllabus.

Profanity and blasphemy were his stated concerns. He read out how many times each unacceptable word appeared in each book - ‘Jesus used in a blasphemous way 56 times’ for example - a list it must have been arduous to compile in the days before digitisation. Listening to him droning on, I pictured rows of old ladies in a church hall somewhere, poring over our set texts while occasionally yelping in horror and having to be revived with sweet tea.

Then came to the councillor’s sideways conclusion: Seamus Heaney should also be removed, not because of inappropriate language but because of the author’s nationalist politics.

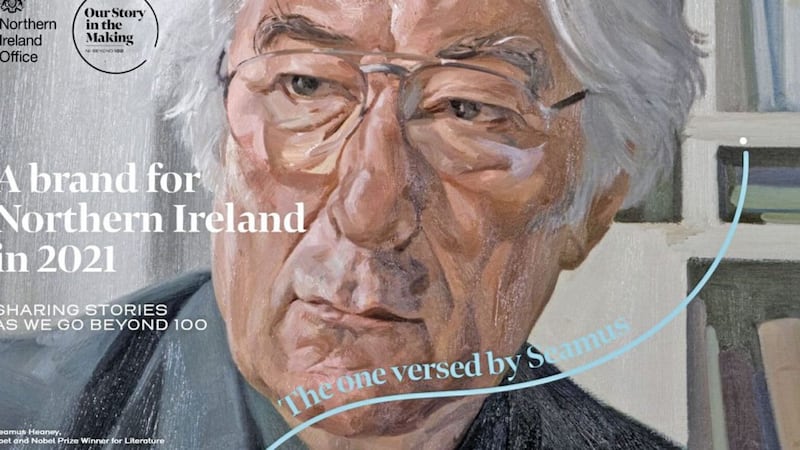

Events this week have brought that experience back. The Northern Ireland Office has used a portrait of Heaney in its centenary promotion.

The response from some nationalists and republicans has been a sly listing of words without context - “be advised my passport’s green, no glass of ours was ever raised to toast the Queen” - followed by censorious non sequiturs. The true argument is ‘you can’t have him, he’s ours’, which is a little different from the councillor’s argument of ‘you can’t have him, he’s theirs’. But it is not different enough.

Everyone should see the value in sharing a figure who can transcend our divide, especially one who did so without flinching from his place in it.

The only other public figure pictured in the NIO promotion, Dame Mary Peters, owes cross-community appeal to a life of diplomatic silence. Perceptions of her background convey a soft unionism by default.

Heaney was unambiguously Irish and nationalist, a figurehead of his tradition and a ruthless critic of mine, yet his intellect and accomplishments left many unionists feeling he belonged to them too.

There is nobody else on any side of Northern Ireland’s “story in the making”, to use the NIO’s awkward slogan, of whom this can be so fully said.

The often-quoted poet John Hewitt, apparently a writer of doggerel by Heaney’s standards, seems valued for qualifying his unionism.

George Best matches Heaney for celebrity but nationalists tend to claim him by implying he had nationalist sympathies, as he advocated for an all-Ireland football team. That was the apolitical view of a professional athlete. In reality, Best is another - albeit edgier - Mary Peters.

Heaney met the Queen on his own terms on her 2011 visit to Dublin and later made light of his quip about not toasting her - his own piece of doggerel, fired off when he learned some of his work had been included in Penguin’s 1982 Book of Contemporary British Poetry.

Being co-opted into Northern Ireland is rather different to being co-opted into Britishness, although again not different enough. It seems vanishingly improbable Heaney would have wished for inclusion in the NIO’s centenary promotion but it also seems likely he would have seen the comedy and been intrigued by the potential for reflection.

Last year, it emerged the NIO had removed portraits of the Queen from its headquarters after a senior official complained they were causing offence.

Secretary of state Julian Smith had to order their reinstatement.

Now Smith’s successor, Brandon Lewis, has ordered a centenary advertising campaign from the same cautious workplace.

It is quite clear Heaney has been featured in an attempt to be as harmless and inclusive as possible, accidentally introducing a subversive element to the proceedings.

Sinn Féin and the SDLP could have filled that role. Seats were reserved for both parties on the centenary forum but they declined to take them, as is their choice, even if makes them look like a fainting church hall. But while no burden of expectation should be placed on anyone to participate, a critical voice is still required.

The decade of centenaries has worked best, or gone wrong least, when easy flag-waving has been challenged with complex histories and other perspectives. Already, unionists and nationalists are looking through Heaney’s writing and interviews to give some nuance to next year. We can all drink to that.