Irish nationalism is on a roll. The great and the good are writing to Leo Varadkar seeking a forum on Irish unity, unionism could lose at least one seat in the forthcoming election and the EU is hammering Britain, apparently on Ireland's behalf.

All of which suggests that this weekend's Sinn Féin Ard Fheis is the spearhead of a nationalist revival, which is about to unite Ireland. Then, as de Valera said, the Irish people, satisfied with frugal comfort, will devote their leisure to the things of the spirit. (He might have been a bit optimistic, but never mind.)

So what constitutes modern Irish nationalism, where is it going and what are its chances of success?

Traditionally Irish nationalism has been anti-British (which was historically inevitable), largely sectarian (Daniel O'Connell welded nationalism to Catholicism) and generally apolitical (it focused on flags, rather than social and economic policy.) Those three elements are still present today.

(British nationalism, on the other hand, has been imperialist, self-righteous and repressive. Not much has changed there either.)

Oddly, modern nationalism's anti-British crusade is led by Fine Gael. Simon Coveney complained this week about Boris Johnson's pledge not to prosecute some British soldiers for their actions here.

(With a wonderful irony, the political descendants of those who used British guns to bombard republicans in the Four Courts, during the Civil War, now argue that some who used British guns here fifty years later should be prosecuted.)

Traditionally, nationalism had two strands: republicans seeking Irish independence (and occasionally, as in 1916, offering radical social and economic ideas) and nationalists, like John Redmond, being prepared to settle for Home Rule. That divide has now been replaced by a broad nationalist consensus for home rule from Brussels. Irish independence has been abandoned.

Modern nationalism's somewhat sectarian nature has been highlighted by criticism of the organisation, Ireland's Future, for not including unionists as signatories to the letters to Varadkar. (There were names from across the Atlantic, but none from across the Shankill or Sandy Row.) This apparent exclusion echoes O'Connell's view that "patriotism and religion run in the same channel."

The letters are interesting in that they appear to suggest that "important" people have more valid views than the rest of us. The latest letter, for example, was weighed down with academics, but there were no lists of bricklayers, labourers or those who run food banks.

This apparent belief that the validity of a view depends on the status of the person expressing it is 1200 years out of date. It was first rejected by the 9th century Irish philosopher, John Scotus Eriugena. (His image was on the Irish five-pound note before Ireland joined the euro and surrendered the right to its own monetary policy - to the cheers of Irish nationalists).

So where is nationalism going? That depends on the fortunes of its iconic political party, Sinn Féin. In the south, SF is likely to hitch its wagon to Fine Gael, thereby risking a repeat of what happened to Clann na Poblachta, led by former IRA Chief of Staff, Seán MacBride. Its 10 TDs entered a Fine Gael-led coalition in 1948. Ten years later it had largely disappeared. Propping up a right-wing government is risky (as the DUP discovered).

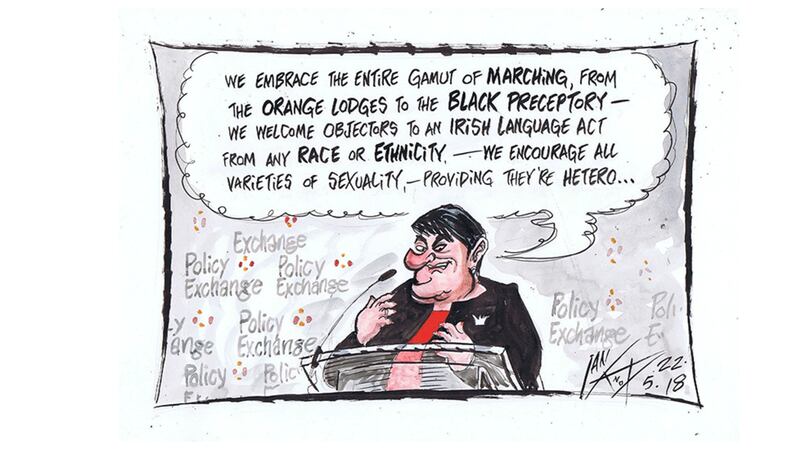

In the north, SF will thrive as long as it has enemies like the DUP and Boris Johnson. But its support base will be sectarian. It operates a bit like a religion in that it asks for faith from its followers. Its adherents are led to believe they will get their reward in heaven, better known as a united Ireland.

But electoral support for SF and hand-picked support for Ireland's Future will not translate into a united Ireland, unless they move away from the confines of historical nationalism. Religious sectarianism, social elitism and an absence of real politics do not constitute Ireland's future. They represent the failures of the past.

Until nationalists learn the difference between nationalism and patriotism, it looks like they are heading back to the future.