IF you too share the privilege of being the parent of primary school child, then there is a fair chance that your week-day evenings are much like my own.

These are generally bookended by the race to get to the after-school care before my son is, once again, the last to be collected and the sweet moment of collapse into bed, an exhausted husk embraced by the arms of Morpheus.

In between, the evenings vanish in a blur. Homework, making dinner, clearing up, decanting the dishwasher, getting ready for the next morning and bundling said child to bed, each element leavened by the Brexit-standard negotiations that constitute domestic diplomacy, are all part of the mix.

Against this frenetic rhythm, my son, aged nine, and I have developed a weekly ritual, a sotto voce respite from the fortissimo.

We lift the 'big' Oxford English Dictionary off the shelf and together look up each of his school spellings - there's usually around 30 - for the week.

I'm not sure which of us looks forward more to this near-sacred time.

In spite of my own desultory offerings in this newspaper, I am fascinated by words and where they come from - oddly, perhaps, few journalists care - and my son has been similarly captured.

The real joy is when we search for a word, as we did earlier this week, like 'elephant'.

These are the baroque diagonals of the looking-up-P6-spellings-in-the-OED world, words whose dictionary definitions lead into hitherto unexplored etymological territory.

I already knew that our word 'elephant' came from Greek. However, I had not realised that the ancient Greek 'elephas' meant simply 'ivory'; that's the way it is used in Homer's Odyssey, for example.

It was only later that elephas was used to also describe the planet's largest land animal.

These are the baroque diagonals of the looking-up-P6-spellings-in-the-OED world, words whose dictionary definitions lead into hitherto unexplored etymological territory

The Greeks, it turns out, were familiar with ivory objects acquired through trading long before any of them encountered the actual animal, whether attached to or separated from its prized tusks.

Knowing all that gives an already satisfying word like 'elephant' a fuller and more satisfying definition than merely settling for 'a big grey animal with large ears and a trunk'.

We do a similar look-up-the-words exercise with his reading books.

The other week, he proudly showed me a page from a Lemony Snicket A Series of Unfortunate Events book.

These are smart, vocabulary-expanding novels, dark and gothic in style with lots of literary references to authors like Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley and Arthur Conan Doyle.

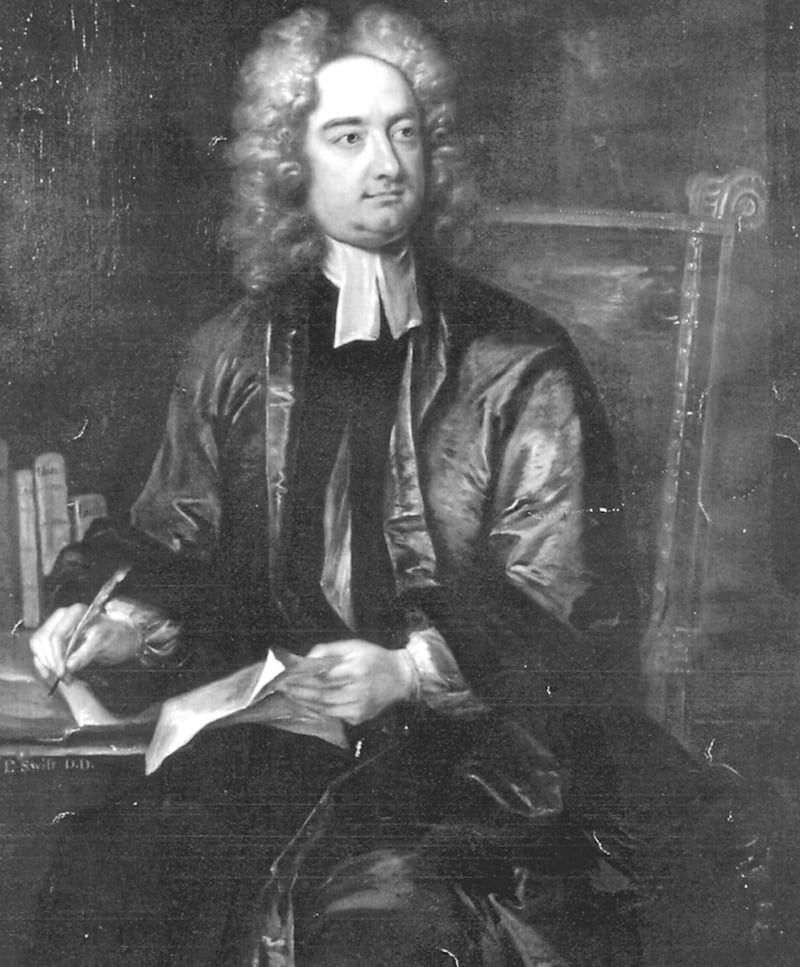

This time, a nod to Jonathan Swift through the use of 'Brobdingnagian' had prompted him to thrust the book in front of me.

By any measure, 'Brobdingnagian' is a fabulous word.

It is one of eight that the brilliant Irish author and satirist invented for Gulliver's Travels in 1726, and relates to the giants who live in the land of Brobdingnag, where everything is gigantic.

In Swift's imagination the opposite place is Lilliput, where the people are tiny in stature as well as small-minded.

Other Gulliver's Travels words include 'Yahoos', the brutish creatures which behave like animals but look like humans, and the wonderfully onomatopoeic 'Houyhnhnm', which he created to describe a race of intelligent horses.

But it was Brobdingnagian which had really wormed its way into my son's head.

He was therefore understandably put-out when, earlier in the school year, his suggestion of the word during a class discussion of alternatives to 'big' was dismissed because no-one else had heard of it. Nor was it to be found in the class dictionary.

Finding it in the Lemony Snicket book, then, was vindication and validation.

It confirmed to him that he had indeed picked the correct word and that he shouldn't have been laughed at by his classmates.

Lemony Snicket's use of the word also demonstrated how using the right word at the right time in the right way gives writing more punch; describing his character as Brobdingnagian, with all the allusion it packs, is so much richer than simply writing about a 'big guy'.

All this word play put me in mind of another Swiftism which seems to capture something of the dead-end in which politics at Stormont has stalled.

The Struldbrugs were a race of immortals who, though they could not die, continued to age and so lived on in perpetual and senseless decrepitude.

Truly, the Struldbrugs are rattling around the corridors of Parliament Buildings, political Lilliputians without the courage to take on the Brobdingnagian challenges of government.