As a new round of talks start, this time with more structure than the haphazard, doomed to fail three weeks of shambolic sitting around that preceded it, there is little to convince me the outcome will be any different.

There are now two weeks not three to hammer out a deal, although that could be a movable deadline and this time head of the civil service Malcolm McKibben is chairing some of the discussions on establishing a programme for government.

What he will not chair is discussions on legacy as Sinn Féin have already objected to Secretary of State James Brokenshire having a role, leaving those talks unstructured.

On Brokenshire Sinn Féin have called it right. The British government is not an independent broker in any legacy discussion and as this paper previously reported favours a 'line in the sand' approach to the past.

Should the parties fail to reach agreement on the outstanding issues - and there is little being said to make me think otherwise - then it will fall to direct rule and to Westminster to make the decisions.

That decision, I'm reliably informed, will be a statute of limitations on all future prosecutions, preventing former British soldiers from being charged with historic killings, saving millions of pounds in legal fees and of course meaning any uncomfortable secrets remains firmly under lock and key.

Britain's exit from the European Union also makes this end game solution harder to judicially challenge.

What access, if any, residents of Northern Ireland will have to the European Court of Human Rights after 2019 is yet another Brexit unknown.

Without a functioning executive and a local solution there is no one to challenge these plans which suits the participants of conflict but shows scant regard for the victims.

Just what other avenue victims will have to 'truth recovery' is a grey area and it also remains to be seen what if anything they can expect from a British administration with Brexit and little else on their minds.

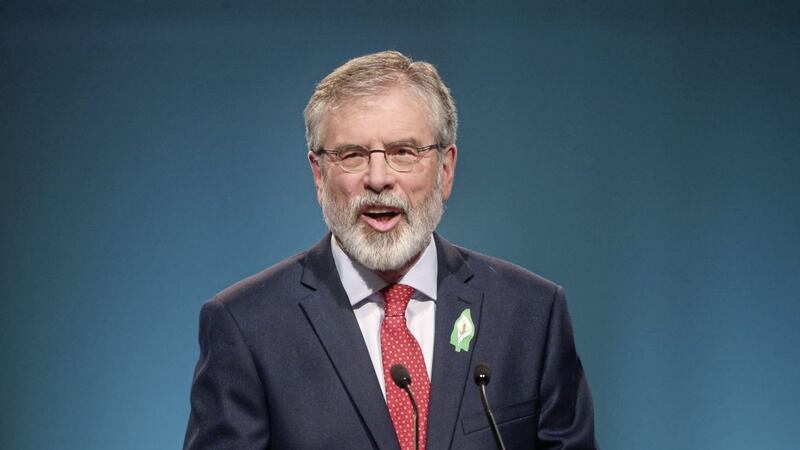

In an interview with Sky News reporter David Blevins this week, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams said he would talk about his long-alleged involvement in the IRA if an independent truth commission was established.

It echoes comments previously made by the late Martin McGuinness, who was always more forthcoming in taking ownership of his IRA status than the party president, someone we've been told countless times was 'never in the IRA'.

"I believe that victims of the IRA, or at least their relatives, have the right to truth and I believe that those who are victims of British Army violence or state violence also have the right to truth and the British government is holding that back", Mr Adams added.

Victims are entitled to answers however those answers are unlikely to come from a truth commission with voluntary participation.

I have spoken to numerous loyalist and republican former prisoners over the years and not one has said they'd tell all in a truth commission.

In fact without exception they've all said 'not a chance'.

Northern Ireland is too small a place to confess your sins in a public forum, the majority of the killings centred around small city clusters or rural areas with interconnected family and business interests.

The reality of the situation is the person who killed your father, mother or son could have been living less than a few streets away or in the next village.

Knowing the details of that but with no legal recourse and a very real chance of meeting that person in the queue in Tesco, would more than likely re-traumatise rather than heal old wounds.

The death and funeral of Martin McGuinness showed those wounds, for some victims, are still very much open and festering.

And for some they will never heal, regardless of what mechanism we use to deal with the past, and that has to be accepted and dealt with in the form of a healthcare package rather than continue to think up new and more public ways to re-traumatise the grief stricken.

Other victims, people like Jude Whyte and Alan McBride, have managed to use their experience to help others, determined not to pass their trauma onto the next generation.

I would argue that they and others like them are the people to talk to about on how best to move the situation on, rather than the British government, the IRA or a loyalist paramilitaries, who all have secrets that they'd prefer kept in the past.