ABOUT twenty years ago when I was minding two young children, the mother picked up a book I was reading and showed it to her friend.

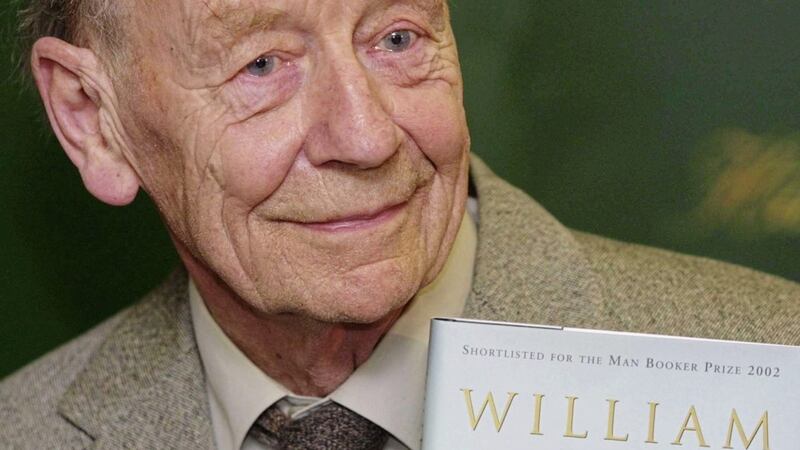

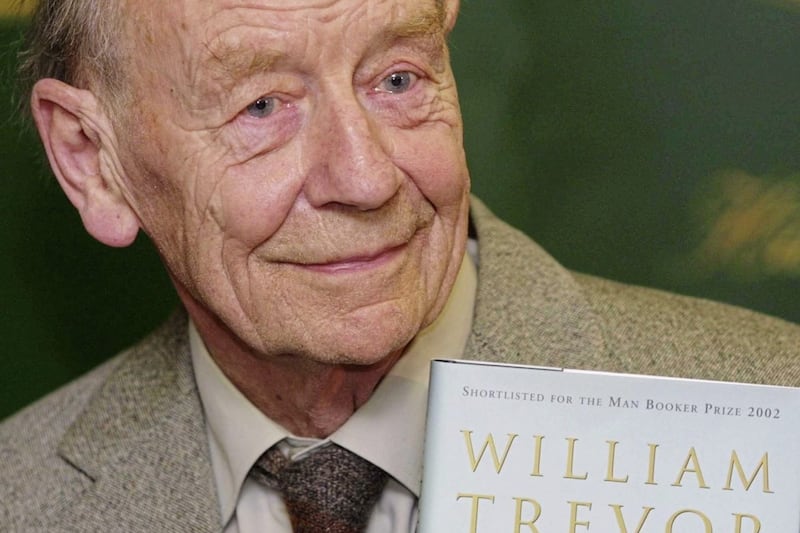

“Isn’t he beautiful?" she said and pointed to a black and white photograph of an elderly man smiling, in bemusement it seemed, on the front cover.

He was wearing a tweed hat and had an incredibly lined face, wrinkles running across his forehead, radiating from his eyes and mouth.

The man, Co Cork writer William Trevor, who died last week at the age of 88, is still smiling from my bookshelf.

That book, Trevor's Collected Stories, saw me through school and university, jobs and relationships and half a dozen different homes.

Its spine is more sellotape than binding now and often two or three leaves come out whenever I read it, but the words are still clear.

Trevor wrote several novels, including the masterful `Felicia's Journey' about a poor Irish girl who goes to England in search of the father of her unborn child, but it's the stories that really linger.

I first encountered his work as a young teenager by reading `In at the Birth'. In the story, an elderly woman called Miss Efoss is asked by a couple called the Dutts to babysit their child Mickey.

What unfolds is horrific, magical, strange in the way that life is strange, and deals with growing old in a way that seems so say so much.

As Miss Efoss says: “The older I become, Mr Dutt, the more I realise that one understands very little. I believe that one is meant not to understand. The best things are complex and mysterious. And must remain so”.

Trevor was, as he put it, a "lace-curtain Protestant" from Co Cork, an Anglican who was not landed gentry. His mother came from a small farm near Loughgall in Co Armagh, his father worked in a bank.

In Ireland we are often too interested in family backgrounds, constantly seeking to define each other by religion or class or money, by the families we come from.

Trevor never sought to classify anyone. He wrote about people, fully-formed people not stick-figure characters plonked on a page.

He imagined what it might be like to be a woman who pretends to sleep with another man so she can obtain a divorce; a middle-aged woman who, realising she is getting older and will be lonely when her father dies, decides to marry a bachelor from the hills; a man who is watching Pope John Paul II's visit to Ireland on television when his home is burgled.

2016 has been a difficult year. A refugee crisis that shows no signs of diminishing, the election of the least well-qualified president in US history and our own fears over Brexit, has left many of us feeling powerless in the face of events that are so much bigger than us.

Trevor understood that feeling, writing often about people who were lost and vulnerable, who felt that they had been overtaken by things beyond their control. He looked at small lives, people who were diminished by their circumstances.

Often in the past few weeks, Trevor’s story `The Hotel of the Idle Moon' has come to mind.

In it, a faithful servant called Cronin is forced to look on as the large English house where he has worked for decades is taken over by a sinister couple, the Dankerses.

He sees his master and mistress die, his world change from a home to a hotel, sees the space where he lives grow smaller until he becomes confined to one room.

He imagines rising up against the Dankerses, cutting down the trees they have planted and killing them.

But his plans are never followed through. And at the end he only sees how “absurd it had been that late in his life he should have imagined himself a match for the world and its conquerors”.

Trevor took care with people and their lives. He humanised people who suffered in large and small ways.

And he did it all in stories that feel effortless but have a depth rarely seen. You could read each work twenty times over and still find new things to see.

How fortunate we are that Trevor gave us the gift of so many stories.

How lucky that he looked so closely, that he saw people as human beings with flaws and strengths and secret troubles, that he saw private joys.