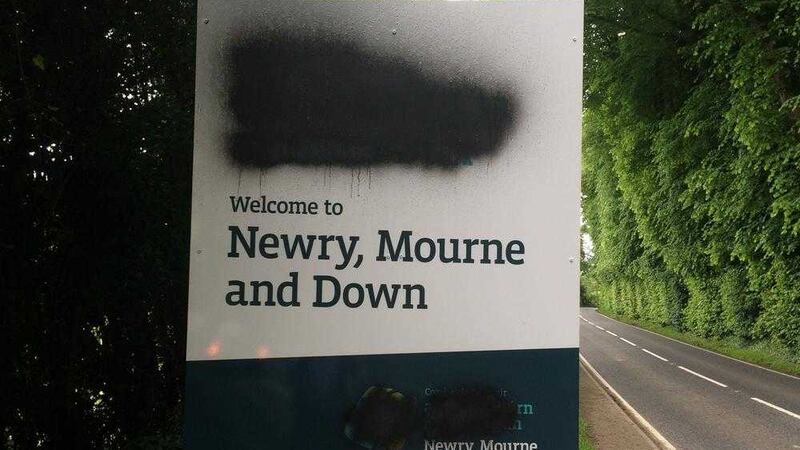

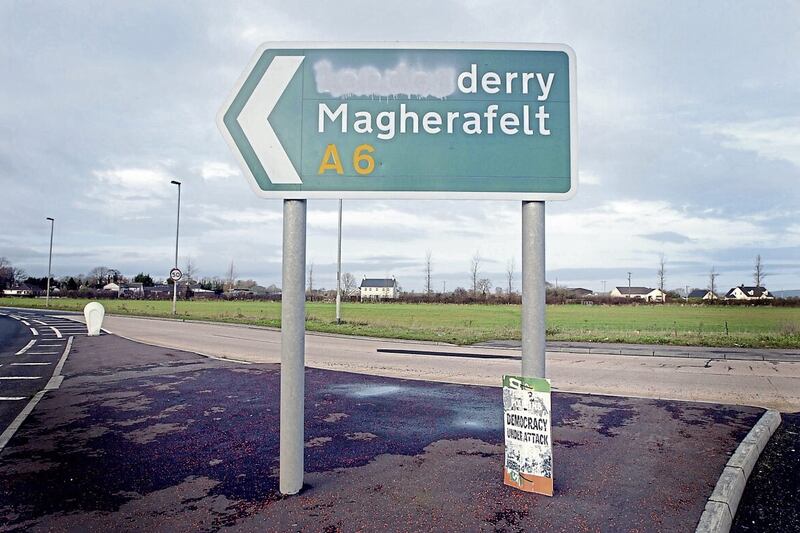

IT is hard to sympathise with Sinn Féin councillors on Newry, Mourne and Down District Council as bilingual signs are defaced in unionist-majority towns and villages.

Four years ago, UUP former transport minister Danny Kennedy put Welcome to Northern Ireland signs around the border in a comparable act of political one-upmanship.

Sinn Féin representatives condemned the inevitable vandalism but were clearly far from heartbroken, mainly complaining the signs were a waste of money in the first place. This has been more or less exactly the response of unionist councillors to the recent damage in Co Down.

Taoiseach Enda Kenny has suggested technology could remove the need for customs posts along a hard border. Perhaps technology could solve the signage problem too. We could take signposts down, like the English did during World War II, as most people already knew their way around and directions were only useful to invading Germans. Then we could simply use Google Maps on our phones, switching to English or Irish as preferred.

If this seems ridiculous it is no more ridiculous than the argument. We can spare ourselves the sophistry that accompanies language `debates' in Northern Ireland, such as how Irish belongs to everyone (except Gregory Campbell) or how most of our place-names are in Irish already (so why have bilingual signs?)

Our dispute on this question is an absolutely bog-standard case of ethnic territorial marking, wearily familiar across Europe and beyond. It occurs even in countries we think of as solidly monolingual like France and Austria and is currently threatening a nightmare scenario in the Baltic, where multilingual signage has been widely outlawed even in overwhelmingly Russian-speaking areas.

This is emblematic of the discrimination that could give Vladimir Putin a pretext to intervene, as he did in Ukraine. Say what you like about spray-painting in Ballynahinch but at least it will not start World War III.

Consequently, signage has been given serious thought at European level. This can offer us guidance and will continue to do so after Brexit, as the basis of language policy in Europe is the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages, an instrument of the Council of Europe, which is separate from the EU.

The UK government has signed and ratified most of the charter with regard to Irish and Ulster-Scots, on both its own and on Stormont's behalf.

Amusingly, Dublin has neither signed nor ratified because it does not want to classify Irish as a minority language. But no matter - like most such documents, the charter is just an unenforceable statement of intents and principles. The most important of these for our purposes is that all language issues are addressed in the context of "national minorities", with no attempt to define `minority' or indeed `language', fortunately for Ulster-Scots and its many continental equivalents.

This decouples language from communication, recognising multilingual street signs for what we know them to be - a coy flag on a lamppost.

Because the charter is unenforceable it has not built up a direct body of law. However, studies on its application point to ways to reduce the risk of a `flag protest'. There should be well-established ways to measure and delineate minority areas, with a town being as valid a unit as a region. A distinction should be made between multilingual signage in public spaces - town boundaries and squares, for example - and ordinary residential streets, where it should be implemented with greater sensitivity.

Signs should show all languages in identical typefaces of equal size and prominence. Unfortunately, nobody in Europe has cracked the problem raised by unionists in Newry, Mourne and Down, who object to Irish being `first'. Nationalists do not want English to be first and short of us all learning Chinese, there does not seem to be a way to put two names on a sign without one being read before the other. Any Irish on a sign in a unionist area seems certain to be defaced regardless.

The `national minority' concept may offer a way around this. It is acceptable under the charter to take "special measures" in favour of a minority, without this counting as discrimination against the majority. If Newry, Mourne and Down classed unionists as a minority in Ireland, the council could put English-only signs in its northern areas, like the Irish-only signs in the Republic's Gaeltacht areas. In short, it could create a Bearlatacht.

There might be just enough sophistry in this to placate both sides. Plus, it would really confuse the Germans.