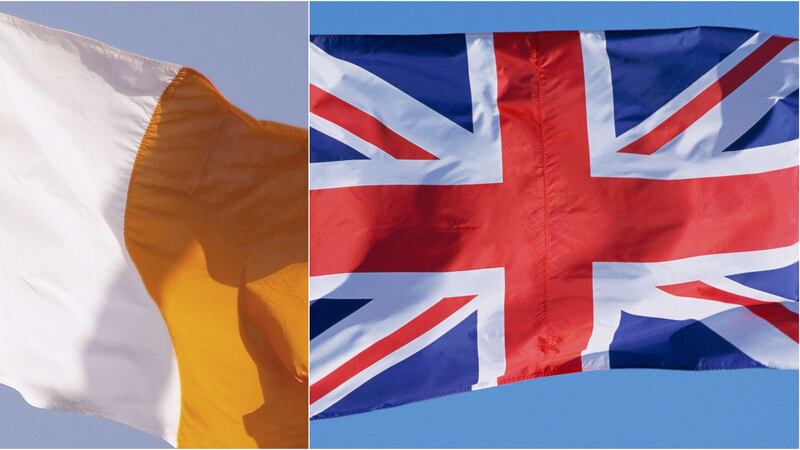

“What does it even mean to be British? That you have to be totally Anglo-Saxon? Or Norman?”

Four women talking in a city centre bar on Saturday evening. As I reached for cash and stretched for drinks, I heard some more.

“I said to dad, you need to stop reading the Daily Mail. But he won’t change. Their whole generation is the same, it’s just where they’re at.”

I scooped up and walked away, thinking about identity.

As of five years ago, the 2011 census found that 89 per cent of the north’s population – about 1.6 million - was born here. (One-in-ten were born in the south, Britain, Europe and farther afield.)

The indigenous proportion regarding themselves as ‘British only’ citizens (around 41 per cent) is now a firmly shrinking minority, and consistently reducing with age. Most other indigenous citizens self-identify as ‘Irish’ and ‘Northern Irish’.

When the overall figures are broken down by age, the results are starker still.

In the over-65s, around 50 per cent are ‘British only’ versus 39 per cent ‘Irish’ and ‘Northern Irish’.

In the 35-to-64 age group, the figure shrinks to 42 per cent ‘British only’ versus 44 per cent ‘Irish’ and ‘Northern Irish’.

The most significant group is the under-35s. This is where the greatest population growth is happening. It’s also where substantial social, economic and political power will rest in 20 years.

In this age group, just 35 per cent identify as ‘British only’, with 28 per cent ‘Irish’ and 21 per cent ‘Northern Irish’. So, collectively 49 per cent of young people now identify themselves directly as citizens of this island – far outweighing ‘British only’ citizens.

If you compare directly between the ‘traditional’ religious backgrounds, Catholics make up 48.4 per cent versus Protestants at 51.6 per cent.

The world is turning. Society is transforming.

As we approach 100 years since the Northern Ireland state was formed, the demographic, cultural and social trends are profound and unstoppable.

The question is how those complex and multi-layered trends will be addressed through long-term political strategy and policy planning.

What’s certain is that the assumptions and conditions promoting the iniquity of partition now rest on quicksand.

That doesn’t inevitably mean a traditional united Ireland 32-county framework will follow. Rather, a discussion must now open about the meaning of self-determination over the next 20 years – conditioned by our actions today.

So, have republicans even properly considered how the words and imagery of Easter Rising commemorations are impacting upon Presbyterians from Parkgate or Methodists from Markethill?

Are unionists capable of accepting an unstoppable new chapter, and turning the page with confidence rather than being constantly constrained by the most negative voices?

What proactive role will the Irish and British governments play in the developing context? Positive and facilitative? Or conservative and unhelpful?

How can the civil service and public service be re-engineered towards enhanced delivery and strategic effectiveness for a new context?

What more is needed to ensure full representativeness in our now fully accountable policing service?

And why have twice as many people (well over 7,000) died by suicide and by alcohol-related deaths since 1998, than were killed in total during the conflict? (Three-to-four times more likely in deprived areas.)

I thought about such questions – and others - last week after watching Laurence McKeown’s challenging drama ‘Those You Pass On The Street’. It’s about the complexities of truth, legacy and humanity (particularly relevant given how Lord Justice Weir has been examining obstructed inquests in recent days).

The play roared the benefits of us all unilaterally exercising and embracing much greater freedoms.

Freedom in decision-making – by stepping outside the old boundaries of constraint and control shaped in conflict, by unilaterally taking positive initiatives.

And freedom in discourse – by challenging and changing the labelling and lies, the cold caricatures and Chinese whispers, the corrosive legacies of conflict.

The play linked freedom to change with futures of healing – where continuous change is central to growth within individual lifetimes, and not simply some ‘legacy’ to be left for subsequent generations.

When the play finished, a question and answer session took place. One young drama student illustrated how far the arrow of time has already travelled.

He said (like his contemporaries) that he’d only ever read about the conflict in his GCSE history book. The same way I used to read about Strongbow and the Norman invasion. Talk about a reality check.

It’s time to start seeing the whole board.