The Guildford Four's Gerry Conlon felt such despair after 12 years in prison that he was on the verge of killing himself, private letters to the Dublin government have revealed.

While languishing in HMP Long Lartin in England in 1987, seven years after his father Giuseppe died in jail, Mr Conlon wrote how he could not face another 18 years of "living hell".

Conlon died in 2014 aged 60, three weeks after being diagnosed with lung cancer.

The letter, dated May 10 1987 and released by the Department of Foreign Affairs in Dublin under the 30-year rule, was sent to then tánaiste and foreign affairs minister Brian Lenihan.

The west Belfast man reflected on the 30-year sentence handed down to him.

"That means if nothing is done to help us I must face another 18 years of a 'living hell'," he wrote.

"I can assure you that I do not intend to serve it, I would much rather join my dear father.

"I can see that if my plight is not resolved in the near future that I will have to decide which form of protest I must take.

"This is not something I want to do but you can only suffer so much and to suffer it for something you didn't do makes the suffering intolerable."

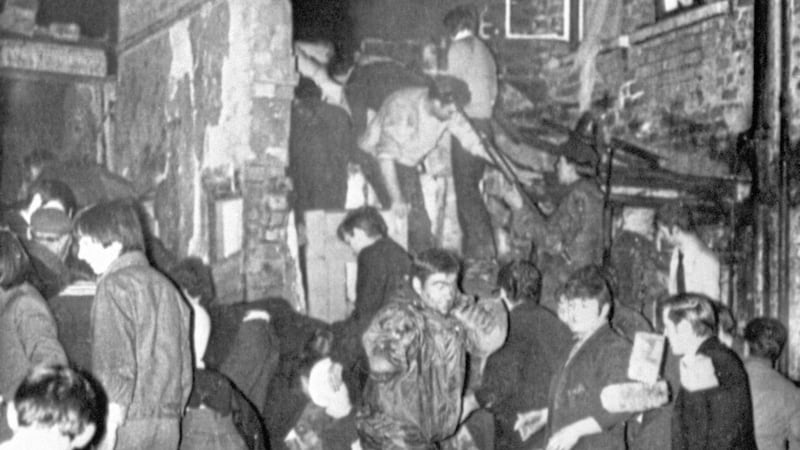

Mr Conlon and the rest of the Guildford Four - Paul Hill, Carole Richardson and Paddy Armstrong - were sentenced to life sentences for the attacks in Guildford, Surrey which killed five people and injured 65.

Their convictions were overturned in 1989.

At the time of their sentencing, the trial judge Mr Justice Donaldson told them: "If hanging were still an option, you would have been executed."

Mr Conlon pleaded with the tánaiste: "I hope the Irish Government will be able to do something to help us before another innocent person, like my father, dies from that terrible disease known as British justice."

The handwriting on the pale blue notepad was impeccable and belied the deep trauma Mr Conlon was suffering and the conditions of life in a maximum security prison.

He told Mr Lenihan he was grateful for the Dublin government's efforts to get justice.

"I can think of nothing worse than putting an innocent person in prison. It has got to be the ultimate 'living hell'," he wrote.

"Moreso, when you know the courts and judiciary know your innocence as well but refuse to admit it because of political decisions and the reputations of those who made their names while framing us."

Mr Conlon contrasted his plight with the approach that would have been taken had an innocent British citizen been jailed in Ireland.

"If our situation was reversed and British people had been framed and railroaded to massive sentences of imprisonment by an Irish court, then I'm sure the British government would have made representations at government level. Indeed, they would have made a diplomatic incident of it," he wrote.

A month later Mr Lenihan replied.

He tried to assure him of his personal support and assistance of the Dublin government but he did not refer directly to Mr Conlon's deep personal despair.

The tánaiste said: "I understand the frustration which you now feel after 12 years of imprisonment. The widespread public sympathy for your predicament and support for your case, however, (may/can/should) be a source of encouragement for you."