ONCE Sir Jeffrey Donaldson’s November 1 deadline for triggering Paul Givan’s resignation passed it became increasingly apparent that the DUP leader planned to string things out, milking his moment, as long as he could. It was the only card he had left to play that would appease the ‘pure’ unionists he’s chosen to woo, a constituency that regards compromise and pragmatism as a sell-out.

The calculation for the DUP was not so much when it ran out of patience with the ongoing EU-UK negotiations on the protocol but how near it could get to an election while gaining maximum impact from Paul Givan’s resignation. The clear aim is to save its own skin, whatever the cost to devolution and public confidence in the institutions, while creating a distraction from the internal turmoil that continues to dog the party.

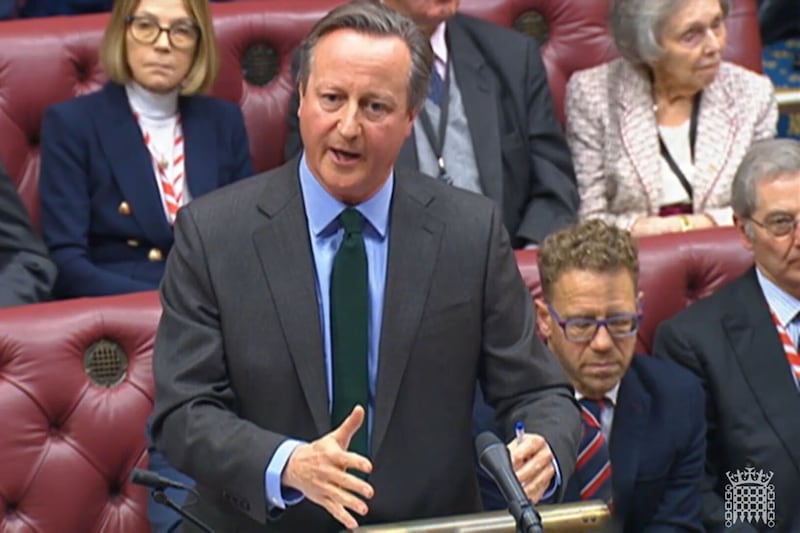

Whether Peter Robinson had a hand in this endeavour is unclear, but it’s straight out of the master tactician, flawed strategist’s handbook. A headline grabbing stunt from which unintended and unknown consequences will flow but responsibility will be denied.

For decades the DUP has had one plan when faced with difficulty, which usually comes about because the party fails to prepare its base for change. But its oft deployed protest approach has diminishing returns, in that it may keep the hardliners sweet but depletes political capital along the way.

Today’s DUP may refuse to acknowledge it, but the party’s greatest electoral strength has been derived from stability rather than chaos. Its most successful and stable years came under Peter Robinson, when it just got on with the job of governing rather than agitating and manufacturing major confrontation. But Brexit blew up in its face and the party is still struggling to come to terms with the fall-out from its ill-advised association with English nationalism's cause célèbre.

The protocol is a consequence of that endeavour and, in some shape or form, it is here to stay. Yet for the sake of self-preservation, Sir Jeffrey behaves like he can force a complete climbdown from the EU at a time when Brussels seems amenable to mitigating the impact of east-west checks. He exaggerates its economic impact, while talking up two nights of rioting by teenagers to the status of civil unrest.

The British government’s inconsistency and ambiguity has also helped fuel uncertainty and instability. Liz Truss, like her predecessor Lord Frost, makes the appropriate diplomatic noises when required but uncritically indulges unionism’s grievances in the belief that it strengthens the British government’s hand. Despite being fooled once, Sir Jeffrey and his colleagues appear content to maintain this expedient alliance.

So as Paul Givan is forced by his leader to vacate the first minister’s office after little more than seven months in the job, we now face the potential prospect of a long election campaign focused on an issue that will only be resolved above the heads of Stormont. The DUP believes the election will be about the protocol and that is correct insofar as the intra-unionist contest will focus on the post-Brexit trade arrangements. However, it is wishful thinking on Sir Jeffrey’s part to assume his short-sighted, selfish game plan will be the one that gains traction at the polls.