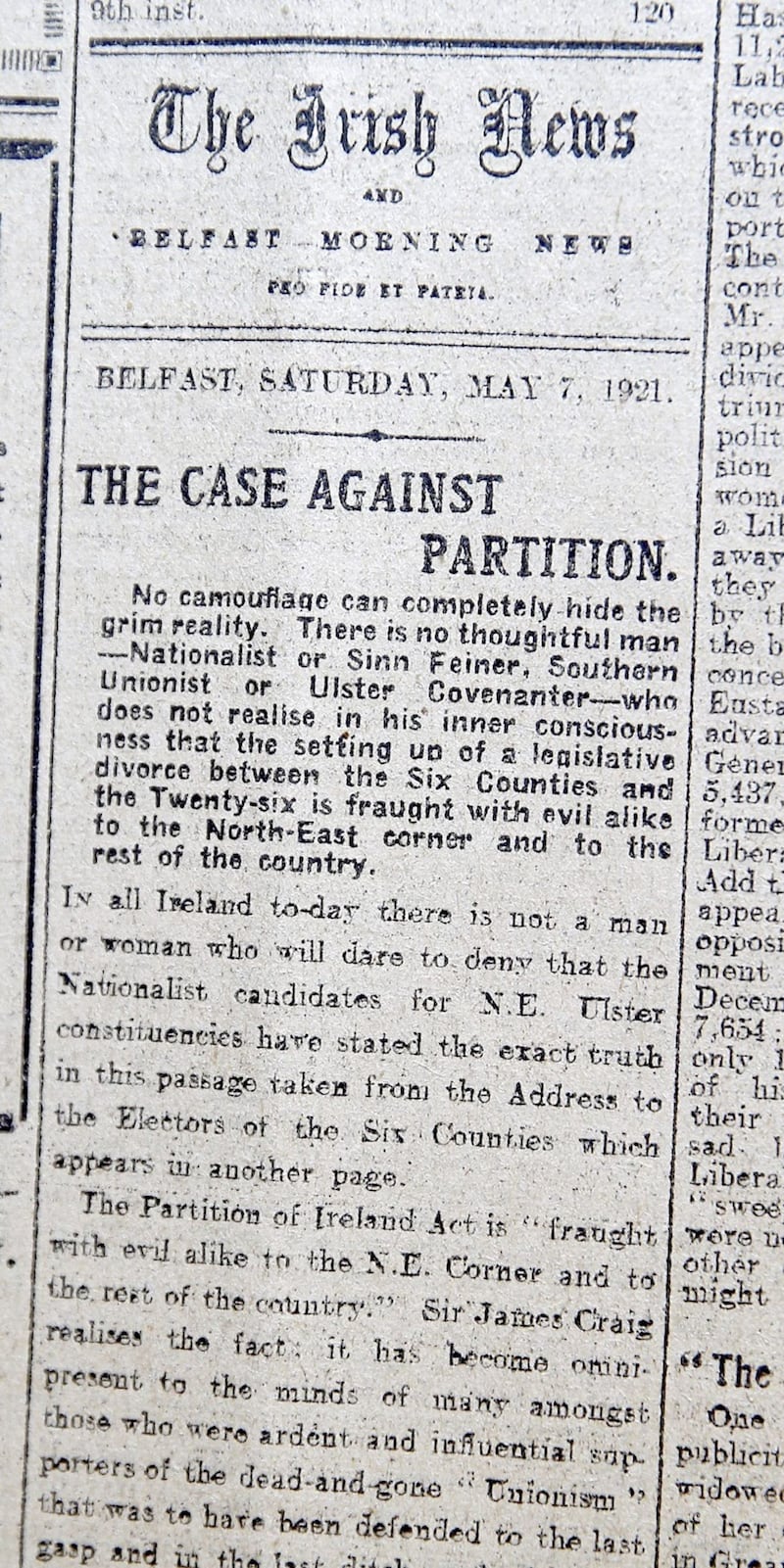

Just a few weeks after Ireland was officially partitioned on May 3 1921, voters in the new Northern Ireland went to the polls.

With the War of Independence still raging, and the north hit by waves of sectarian violence, the May 24 election would prove to be vital in the formation of the new state.

Two elections were held in Ireland following the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which established the House of Commons of Northern Ireland and the House of Commons of Southern Ireland.

No polling took place in the south where all candidates were elected unopposed. Sinn Féin won 124 seats and independent unionists won four.

It was a different story in the north, with unionists and nationalists engaged in fierce rhetoric over partition. Unionists desperately wanted a clear mandate for partition while nationalists tried to stave off the break-up of Ireland.

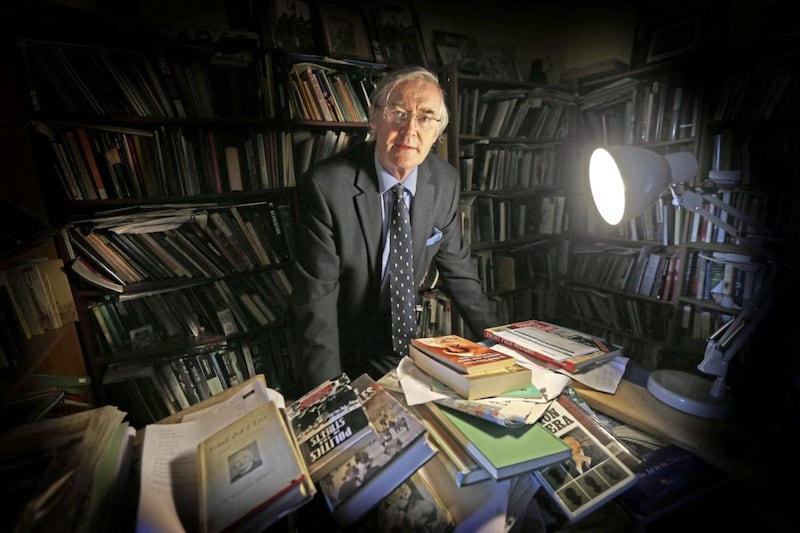

Dr Éamon Phoenix said the election in the north was marked by sectarian violence, particularly in Belfast, including attacks on nationalists and by the IRA.

“In the run-up to the elections there were mobs with revolvers who fired them into the air,” he said.

“The Ulster Hall was seized by shipyard workers and Labour candidates were excluded forcibly.

“There were huge attacks on the ‘Church of Rome’ which the shipyard orators declared was the cause of the First World War.

“Also on election day the Specials, who were the auxiliary police, who were all loyalists, they were very active at the polling stations and they intimidated nationalist and Sinn Féin election workers and people who came to claim their votes in areas in which they had been intimidated (out of their homes during sectarian violence)… You had lots of complaints that Specials were turning nationalist voters away and that the register had been impersonated.”

He added: “You had IRA attacks as well. Violence was raging across Ireland and the IRA began to up the ante towards polling day, bombing barracks like Springfield Road barracks in west Belfast."

“A little girl was fatally wounded in the head as she returned from a Sinn Féin meeting in North Queen Street (in north Belfast). They were going close to (predominantly unionist) Tigers Bay. Shots were fired into the crowd and this little girl was hit and died later," he said.

“It’s a very, very violent time.”

Only men over the age of 21 and women aged over 30, who also met some property requirements, were allowed to vote in the election, which was held under proportional representation (PR) as a safeguard for nationalists in the north.

The population was roughly two-thirds Protestant, one third Catholic, at the time but Ulster Unionist leader James Craig was adamant that the ‘Union Jack must sweep the poll’.

Sinn Féin and the Nationalist party agreed a pact, based on anti-partition and abstentionist policies.

Sinn Féin stood its biggest figures, including Éamon de Valera, Michael Collins, Eoin MacNeill and Arthur Griffith in northern seats as well as in the south.

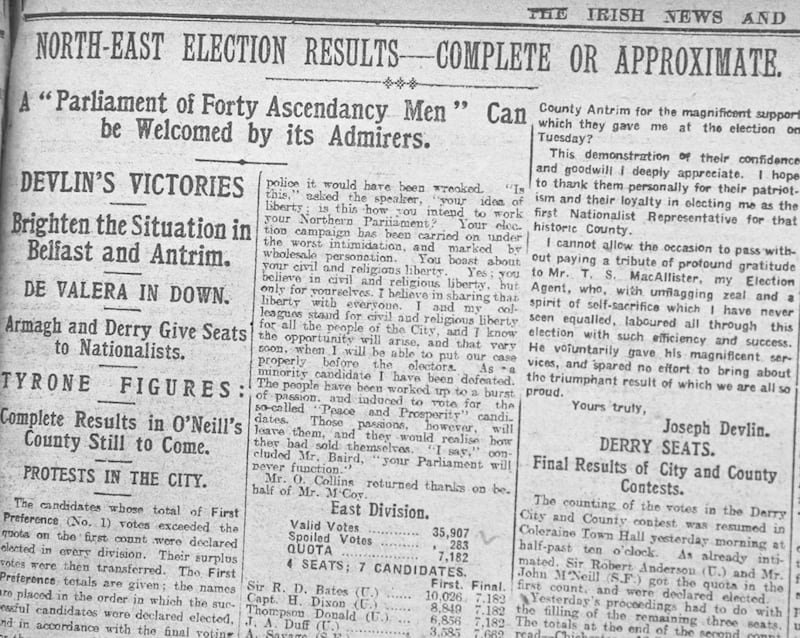

Yet despite all four being elected - Collins in Armagh, de Valera in Down, Griffith in Fermanagh and Tyrone and MacNeill in Derry - in the end the unionists swept the poll, winning 40 of the 52 seats. Sinn Féin and the Nationalist party only won six seats each.

Dr Phoenix said nationalists were stunned by the poor result, but divides between the anti-partition parties had split the vote.

“There was bad blood on the ground between Sinn Féin and the Home Rule party,” he said.

“That was reflected really in a reluctance in some areas to transfer… Each side blamed the other for partition.

"Sinn Féin blamed (Nationalist leader) Joe Devlin and his party for accepting the idea of exclusion of various counties, the nationalists blamed Sinn Féin for abstaining at Westminster and allowing (Ulster Unionist Edward) Carson to dominate Irish politics.”

Craig topped the poll in Down, followed by de Valera. The election also saw Richard Dawson Bates, the UVF organiser in Belfast after 1913, winning for the Ulster Unionists in the east of the city.

Dr Phoenix said the election result gave Craig “constitutional security to ensure the continued existence of the state”.

“It gave him a kind of veto on a united Ireland in any future negotiations,” he said.

During negotiations in London later in 1921, efforts to overturn partition failed.

“Even though Sinn Féin, led by Griffith and Collins at the subsequent negotiations in London, would try to overturn partition… they were constantly confronted with the constitutional establishment of a parliament and government in the north that they couldn’t really undermine,” Dr Phoenix said.

“The election is the anchor of partition.”

For more than a decade, the new Northern Ireland Parliament sat in assembly rooms on Botanic Avenue in Belfast while the new Parliament Buildings were built at Stormont.

Nationalist MPs would not take their seats until several years after the election. However, in the decades the parliament lasted nationalists would frequently abstain as a protest against partition.

“That parliament will last for 50 years," Dr Phoenix said.

"It will pass the Special Powers Act in 1922, will introduce internment. It will abolish proportional representation which was a minority safeguard…It will provide for gerrymandering west of the Bann to ensure unionist control.”

He said the new parliament introduced laws with “scant regard for the Catholic minority”.

“The election establishes a state that no nationalist has even contemplated a decade before,” he said.

“For the next 50 years unionists dominate... The minority were never consulted about partition. Their concerns were rejected. Devlin had demanded PR, he’d demanded extra nationalist seats in the Senate (the upper house of the Parliament of Northern Ireland) so they would have a supervisory role over legislation. All of that is rejected.

“As unionism establishes its government and parliament, the nationalists become a state within a state. They had their own schools, their own church, their own cultural activities - the GAA, the Irish language, they have their own newspaper - The Irish News, they even have their own hospital - the Mater hospital.”

:: Dr Éamon Phoenix is a political historian and broadcaster and an Irish News columnist. He is a member of the Taoiseach’s Expert Advisory Group on Commemorations.