IT was on this day in 1921 that the Government of Ireland Act, effectively partitioning Ireland and establishing a Unionist-dominated sub-state in the six northern counties, came into effect.

It was a day The Irish News and northern nationalists had hoped would never come to pass.

The immediate background to partition was the success of the Unionists and their Tory allies before the First World War in using the threat of violent resistance to prevent a weak Liberal government - reliant on the support of John Redmond’s Irish Nationalists - from going through with its policy of all-Ireland Home Rule.

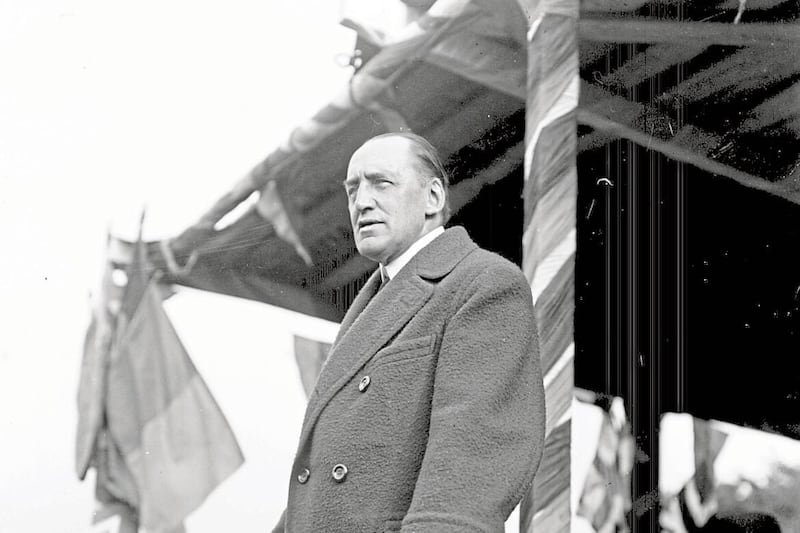

The unconstitutional actions of Edward Carson, a charismatic Dublin lawyer, and his deputy, James Craig, in raising the UVF and arming it with German rifles had the unintended effect of re-igniting the flickering flame of violent Irish republicanism.

In response 200,000 men joined the Irish Volunteers.

With no compromise in sight and partition threatened, Ireland seemed on the brink of civil war by 1914 - a conflict only averted by the outbreak of the Great War.

The 1916 Rising and the executions of its leaders saw the triumph of Sinn Féin in the 1918 general election and its establishment of Dáil Eireann as the government of an all-Ireland republic.

In Britain, the return of a Tory-dominated coalition under Lloyd George ensured that partition would become a ‘fixed idea’ of British policy.

The decision of Sinn Féin to abstain from Westminster meant that the balance of power shifted from the Irish Nationalists to the Ulster Unionists led by Carson and Craig.

The northern Nationalist leader, Joe Devlin, was a lone voice in the overwhelmingly Tory House.

The Ulster Unionists were particularly fortunate that the fourth Home Rule Bill – and the only Home Rule measure ever to come into even partial effect - was drawn up as a result of close consultation between them and the British Cabinet.

Indeed, several of their number, including Craig, were junior ministers in the coalition. The nationalist minority in the north was simply ignored .

At the end of 1919, against a background of the escalating War of Independence in Ireland, a cabinet committee was set up under Walter Long - an Anglo-Irish Unionist - to frame a Home Rule Bill.

It was clear that such a measure would contain the principle of partition but it was felt that if American opinion was to be conciliated, it must appear to pave the way for an all-Ireland parliament in the future.

The Long Committee was tempted to include the historic nine-county unit in the new state on the twin grounds that it would be more ‘defensible’, while its large (43 per cent) Catholic population might make Irish unity more likely.

In the end, however, the Lloyd George cabinet reluctantly gave way to Craig’s arguments that a six-county bloc would provide a more ‘homogeneous’ and viable area for unionism.

In a critical intervention on November 13 1919, Craig told Long that "Protestant representation would be strengthened".

Craig had laid bare the sectarian headcount underlying Unionist thinking.

The 1920 Act divided Ireland into two jurisdictions, each having its own regional parliament and government.

This was a new offer to the north and realised the worst fears of northern nationalists, with control over such contested areas as security and education.

The Act was a major triumph for Craig though he lost one battle: he was forced to accept ‘a bond of union’ between north and south in the shape of a powerless Council of Ireland.

However, on virtually every other issue his views were accepted by the British government.

Thus, when the southern unionists proposed Senate chambers, north and south, to give protection to minorities, Craig ensured that the northern body – unlike its southern counterpart – was as harmless as possible.

He also rejected PR - a key minority safeguard in the Act - and pledged to abolish it.

On the Nationalist side, only Joe Devlin, a solitary figure at Westminster, saw the dangers of the ‘Partition Act’.

He railed against it as portending both ‘permanent partition’ and ‘permanent minority status’ for northern Catholics, noting: "We Catholics and nationalists could not... consent to be placed under the domination of a parliament so skilfully established as to make it impossible for us to be ever other than a permanent minority with all the sufferings and tyranny of the present day continued only in a worse form."

Not without justification, the Falls MP attacked the glaring lack of safeguards in the Act for the one-third nationalist minority.

In particular, he lambasted the government’s failure to provide nationalists with extra representation in the proposed northern Senate.

The need for such safeguards, he told the Commons, was underlined by the tragic sectarian bloodshed in north-east Ulster in the summer of 1920 against the backcloth of the Anglo-Irish War.

The worst episode occurred in Belfast in July 1920 when the assassination of a northern-born RIC officer in Cork resulted in the mass expulsion of some 8,000 Catholic workers from the shipyards and other industries.

These events were a foretaste of the serious sectarian disturbances which were to scar the face of Belfast and other northern towns during the next two years.

The effect of these ‘pogroms’, as The Irish News described them, was ultimately to reinforce nationalist resistance to partition.

Over 450 people, the majority of them members of the Catholic community, died violently during the black days of 1920-1922.

In a reference to the sectarian violence, Lloyd George admitted: "Our Ulster case is not a good one."

The upsurge of violence in the north had two important effects.

First, it seemed to confirm nationalist fears of being subjected to the rule of the unionist majority in a separate state.

Secondly, the mounting unrest led Lloyd George to endorse Craig’s scheme for a new auxiliary police force.

Formed in October 1920, the Ulster Special Constabulary – formed from the pre-war UVF – was to play a crucial role in the enforcement of the new Irish border.

In nationalist eyes, however, this sectarian force was viewed – in the words of a British official – "with a bitterness exceeding that which the Black and Tans inspired in the south".

Craig also secured the appointment of a new Under-Secretary for Ireland, Sir Ernest Clark, based, significantly, in Belfast.

Clark, a pro-Unionist English official, lost no time in laying the foundations for a separate administrative and policing authority for the new state, working hand-in-glove with the Unionist leadership in the ‘Old Town Hall’.

Embarrassed by the sectarian complexion of the new northern civil service, Whitehall tried to have a few Catholic officials appointed but found these rejected by Craig.

In the case of HP Boland, an "exceptional" official but an Irish Catholic, Clark informed the British Treasury: "...the decision of the northern government is 'thank you but no'. I believe you know why."

Incredibly, the British government acquiesced in this blatantly sectarian policy.

On May 3 1921, the ‘Partition Act’ became operational. Elections to the new Belfast parliament were set for May 22.

Two days later, Craig shocked his more extreme supporters by meeting Eamon de Valera secretly in Dublin.

The meeting was unproductive - part of a series of peace feelers by Lloyd George who was preparing to make an offer of dominion status to the south once partition had been achieved.

Standing firm on ‘Crown and Empire’, Craig insisted that only a record poll would prevent the "submergence of Ulster in a Dublin Parliament".

Devlin and de Valera forged an electoral pact, based on abstention and Irish unity. Devlin’s slogan was stark: "Partition means National Suicide".

In the event, Craig scored a remarkable triumph, winning 40 of the 52 seats under PR.

The Nationalists and Sinn Féin – with a third of the total vote between them – secured six seats each. Michael Collins was elected in Armagh and de Valera in Down.

Craig lost no time in establishing his new administration. The blunt Orangeman had secured the ‘homeland’ he had long sought for his own people.

Finally, on June 22 1921, the King, George V, arrived in Belfast to open the new northern parliament in Belfast City Hall.

"From that moment", Churchill wrote perceptively, "Ulster’s position was unassailable".

However, the King was determined to use his speech as an ‘olive branch’ to Sinn Féin in the South.

In a script, heavily over-written by the King, Lloyd George and the South African Prime Minister General Smuts (who had secretly met de Valera), the King appealed "to all Irishmen to pause, stretch out the hand of forbearance and conciliation".

The royal speech was to prove the turning point in the relationship between the British government and Sinn Féin.

Within three weeks a truce had been arranged and de Valera was invited to London to meet Lloyd George.

As violence continued in the north, nationalists could still hope that partition might yet be overturned by the Sinn Féin negotiators.

But, as the 1921 Treaty would confirm, it was to prove a fatally false hope.

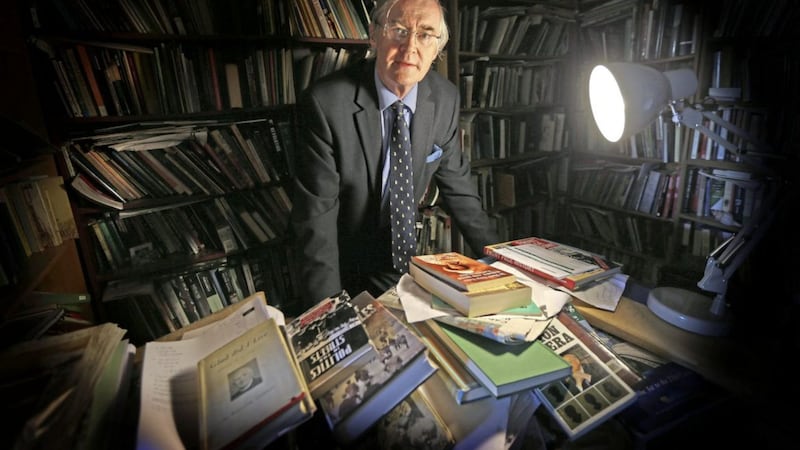

:: Dr Éamon Phoenix is a political historian and broadcaster and an Irish News columnist. He is a member of the Taoiseach’s Expert Advisory Group on Commemorations and the author of Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland 1890-1940.