ANTI-SOCIAL behaviour has tripled at Northern Ireland's so-called peace walls a report has revealed - 50 years after the first physical barriers dividing neighbourhoods along sectarian lines was built.

The `Community Attitudes to Peace Walls Survey' was launched yesterday at Girdwood Community Hub, a former army barracks which has become the focus of arranged sectarian street fights among Catholic and Protestant youths in recent years.

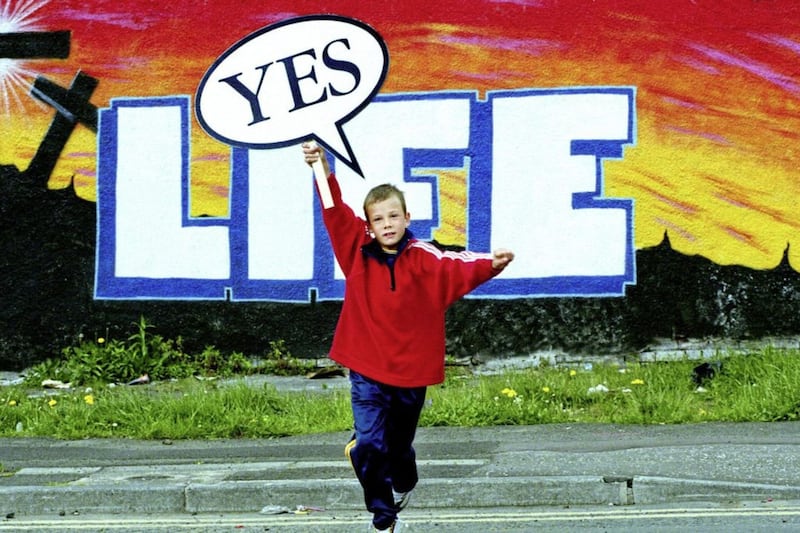

With just four years until the Executive hoped to have removed all peace walls, its findings show little appetite for their dismantling within this "generation" of residents.

Just 18 per cent of those living beside the barriers believe they have "no function" and could be taken down today - a five per cent rise since the same survey two years ago.

While 67 per cent believe they "have a negative impact on health and wellbeing of residents", three-quarters want removal "within the lifetime their children or grandchildren" rather than their own.

The study reveals continuing unease about safety within communities on both sides of the divide, with 36 per cent saying "additional security" would be needed before they would change their minds about `peace line' removal.

Since the `baseline' survey in 2017 there has been a marked rise in anti-social behaviour in the areas, with 34 per cent now naming it "the key issue of local concern" - up from 10 per cent.

While drug misuse one element recorded, police are an increasingly familiar presence at interfaces as children as young as 10 are being drawn into sectarian violence.

The Peace Walls Programme (PWP), funded by the International Fund for Ireland (IFI), was developed in 2011/12 to assist communities living in the shadow of the barriers with the aim of helping them "to reach the point where they feel ready" to discuss "options in relation to changes to barriers".

The projects are Upper Springfield/Black Mountain in west Belfast, Bishop Street/Fountain Estate in Derry, Lower North Belfast at Duncairn, Greater Whitewell on the ourskirts of north Belfast, Lower Oldpark/Cliftonville and Ardoyne - both also in the north of the city and Ardoyne/Upper Ardoyne Twaddell/Woodvale in the north west of the city.

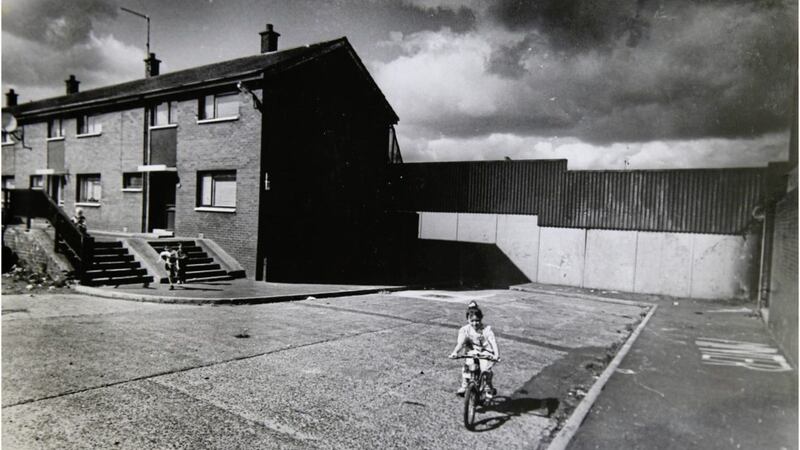

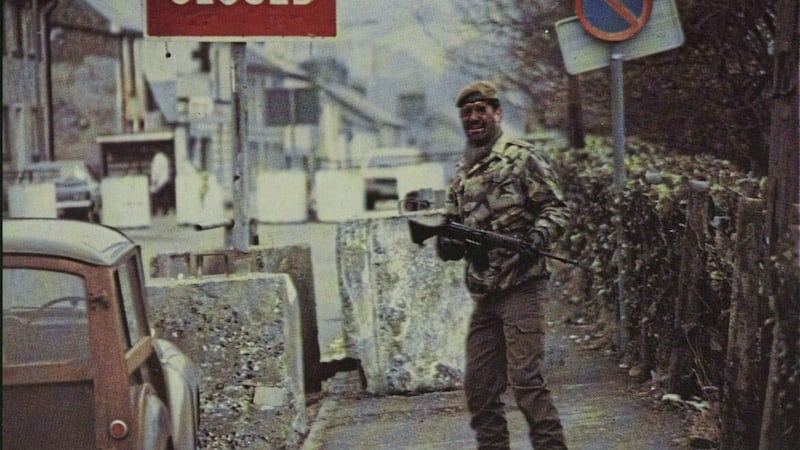

On September 9 1969, following the outbreak of civil unrest and rioting, Northern Ireland prime minister James Chichester-Clark and his joint security committee decreed: "A peace line was to be established to separate physically the Falls and the Shankill communities.

"Initially this would take the form of a temporary barbed wire fence which would be manned by the army and the police.

"... It was agreed that there should be no question of the peace line becoming permanent although it was acknowledged that the barriers might have to be strengthened in some locations."

A day later, British Army Engineers, escorted by the 2nd Grenadier Guards, started work in two locations in west Belfast on the first `peace lines', drilling pickets into the road surface and attached barbed wire to separate portions of the Falls and the Shankill areas.

The Belfast Interface Project's latest map identifies a total of 97 peace walls and barriers across Belfast, 11 barriers in Derry, one in Lurgan and seven in Portadown.

The Department of Justice claims ownership of 59 of the structures and the Housing Executive a further 20.

According to the report, communities bordering them "experience high levels of multiple deprivation" and "stigma".

It also suggests a loss of faith how their removal is managed due to "bureaucracy, red-tape and long delays", a process, Paddy Harte, International Fund for Ireland chairman, said is being "hampered... (by) ongoing political uncertainty".

The `Aftercare Package' pledged in the 2013 `Together Building a United Community', which would provide enhanced security at the most vulnerable homes, is still not available.

"We cannot fund the physical removal of barriers nor fund the much-needed economic and social regeneration of interface areas following removal," Mr Harte said.

"These are the responsibilities of the relevant departments and agencies who own the barriers and/or who have responsibility for regeneration programmes.

"... Political will and leadership is essential alongside the necessary ring-fenced resources and funding. Increased collaboration is critical to advance barrier removal and regeneration for local communities living in interface areas."