ON THE the second day of the Battle of the Bogside on August 13 radical MP Bernadette Devlin contacted the Republic’s Ministry of Defence to request protection against “a united force of police and Paisleyites”.

Loyalists were now burning houses and shops on the edge of the Bogside. Already Paddy ‘Bogside’ Doherty of the militant Derry Citizens’ Defence Committee (DCDC) had been to Dublin where he met separately Irish officials and the IRA chief of staff.

The latter, the Marxist Cathal Goulding, could offer no protection but – to Doherty’s horror – offered to shoot Robert Porter, the unionist minister of home affairs.

The cabinet of taoiseach Jack Lynch, right, were still trying to formulate an agreed policy on the crisis while the ‘republican’ Charles Haughey/Neil Blaney faction favoured military intervention – a high-risk strategy which might provoke a sectarian blood-bath in Belfast, as Lynch’s Rostrevor-born adviser, TK Whitaker warned.

In the end, at 9pm on Wednesday August 13, an emotional taoiseach made a dramatic broadcast to the nation.

Blaming the northern crisis on the policies pursued by successive Stormont governments, he stated that “the Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured or perhaps worse”.

Read More: Dr Éamon Phoenix on how August 1969 changed Northern Ireland forever

Lynch called for a UN peace-keeping force, sent troops to the border and established a field hospital near Derry.

Dublin’s intervention provided a morale-boost for the Bogside defenders but it outraged the Stormont government and unionists across the north.

It also enraged the British government, while prime minister of Northern Ireland James Chichester-Clark condemned Dublin as an “implacable government” determined to overthrow the “democratic” northern state.

As RUC armoured cars roared into the Bogside and Stormont mobilized the B Specials, Derry priest Fr Anthony Mulvey feared “the point of no return” had been reached.

On August 14 Chichester-Clark requested troops.

British home secretary Jim Callaghan and prime minister Harold Wilson, meeting in Cornwall to discuss the crisis, agreed.

At 4.35pm, British troops entered Derry as the RUC withdrew.

The RUC had been defeated in Derry – that was how the force, nationalists and the broad unionist population saw it.

But as Derry celebrated on the evening of Thursday August 14, Belfast’s agony was only beginning.

Read More

- Unonists believed IRA used Bogside to undermine NI state

- Timeline Battle of the Bogside

- Still a need to recapture spirit of Free Derry, says Eamonn McCann

The Civil Rights Executive had called for a series of protests across the north “to take the heat off Derry” and on August 13 a crowd of around 100 protesters attempted to deliver a petition of protest at Springfield Road RUC station.

When the petition was refused, the crowd marched to Hastings Street station where petrol bombs were thrown.

In response to this and a blast bomb on the Falls Road, a senior officer ordered the deployment of three Shorland armoured cars fitted with heavy Browning machine guns.

These weapons were capable of firing up to 600 rounds per minute in long bursts – as the events of that night confirmed.

In the view of the Belfast police commissioner Harold Wolseley, the Stormont government and the loyalist mobs mustering on the Shankill Road close to the Falls interfaces, the minor rioting in Divis Street/Falls Road that night, taken in conjunction with the Bogside battle and Lynch’s broadcast, constituted a major IRA uprising.

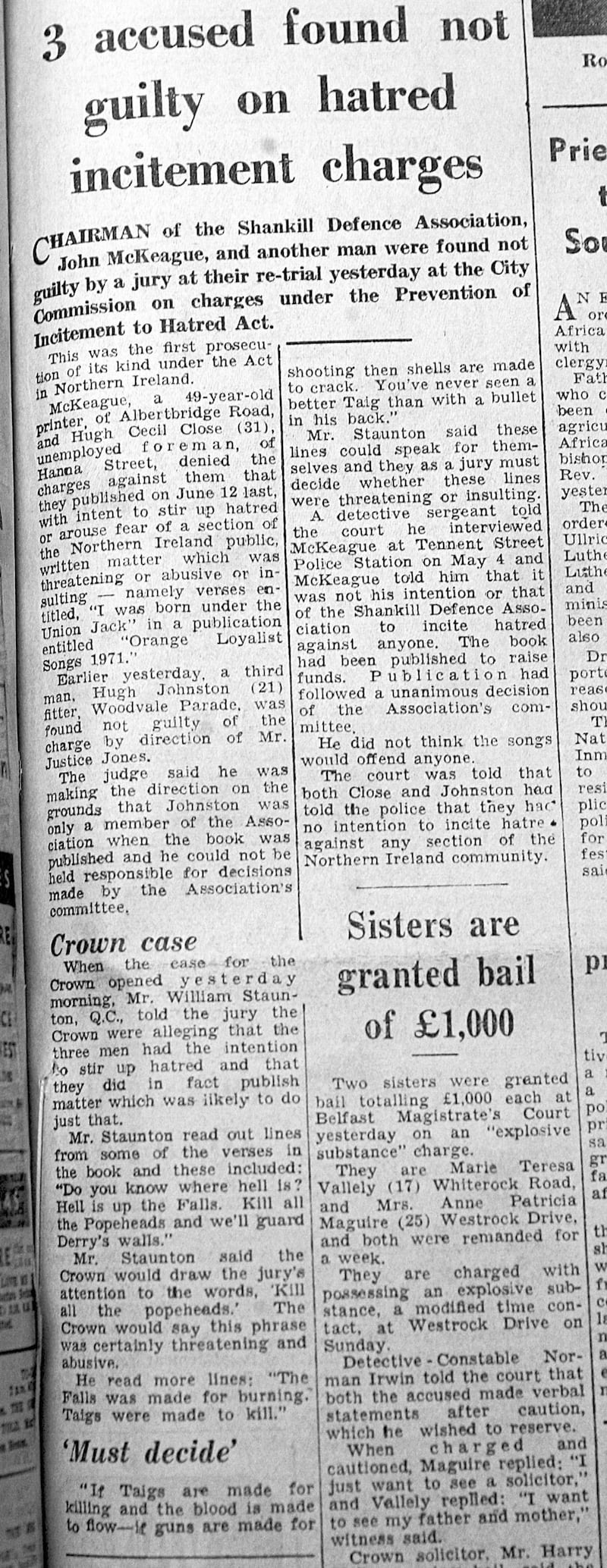

As well as the police’s fire-power, armed B Specials were mobilising on the Shankill while loyalist John McKeague, of the Shankill Defence Association, ordered his sectarian bandits to bring their licensed firearms to the area.

As the later Scarman Inquiry into the 1969 riots across Northern Ireland noted, the RUC made no effort to curb McKeague’s warlike preparations, “regarding [loyalist] activities as defensive, perhaps legitimate”.

The scene was set for what Belfast Catholics understandably saw as an organized pogrom against their lives and property as loyalist mobs, orchestrated by McKeague and his sectarian counterpart John McQuade, an extremist unionist MP, and accompanied by gun-toting Specials, followed the RUC patrols and armoured cars into the Falls area.

Fionnuala O Connor: Fifty years ago we were sliding into a disaster that continues to reverberate

That night and on the following day some 600 houses were destroyed in west and north Belfast.

As Catholics fled their homes and sought to resist with petrol bombs, Scarman noted that the loyalist mobs invaded the Catholic area, penetrating Divis Street where McKeague triumphantly raised a

Union flag.

“We gave them a lesson they will never forget,” McKeague told the Scarman Tribunal a year later.

Catholic witnesses testified to the failure of the RUC to protect their homes from being burned.

The IRA, as in Derry – politicised since the Border Campaign of the late 1950s –- were in no position to defend the Falls.

But late in the night a few guns were produced on the Catholic side and directed at the loyalists.

Against this background and convinced of the Stormont theory of an IRA insurrection, assisted by Lynch and the Republic, the three armoured cars roared up and down Divis Street firing their heavy calibre machine guns down streets and, fatally, into the high-rise Divis Flats.

By morning, seven people had been shot dead in the city. They included three in the Falls area: nine-year-old Patrick Rooney, fatally wounded as he slept in Divis Flats; Hugh McCabe, a teenage British soldier home on leave; and Herbert Roy, identified by Scarman as member of the Loyalist mob.

Both the boy and Trooper McCabe were killed by RUC fire.

In Ardoyne three men were shot dead: Sam McClarnon, a bus conductor killed in his own home; Michael Lynch and David Linton.

The first two died from police fire, Scarman concluded.

On the same night, 27-year-old John Gallagher was shot dead by B Specials in Armagh following a civil rights march.

The assassins were identified as members of the 13-strong Tynan platoon of B Specials who fired on the civil rights crowd without warning at 11.20pm.

On the next day, Friday August 15, British troops were finally sent into Belfast but were unable to prevent the burning of Bombay Street in the Clonard area by an armed mob.

A 15-year-old boy, later claimed by the republican movement as a member, was shot dead nearby by loyalists.

As an uneasy peace descended on Belfast, the city resembled a war zone.

British soldiers were initially welcomed in Catholic areas in Belfast and Derry.

The IRA’s ineffectiveness during the onslaught would later precipitate a bitter split in the republican movement and the emergence of the militant Provisional IRA.

However, the situation remained confused.

For the Catholics of west and north Belfast, they had been subjected to a merciless sectarian onslaught – a virtual pogrom.

The Falls MP Paddy Devlin, who was present during the violence, accused the unionist government of having given the B Specials “licence to kill with impunity” while condemning the reckless firing by the police armoured cars on the Falls.

The breakdown of trust between the RUC and the Catholic community – 35 per cent of the population – was now total.

Yet Chichester-Clark – to the raucous amusement of a packed press conference afterwards – insisted that the violence was caused by “a subversive Republican element” and the police had merely returned the IRA’s fire.

The unionist cabinet quickly realized they had lost the propaganda war as pictures of a smouldering Bombay Street were flashed across the world.

As Devlin and other nationalist MPs sought guarantees of future protection, even the promise of guns, from a cautious and divided Dublin government, the British Labour cabinet met on August 19 to assess the situation.

Most ministers were sympathetic to the nationalist minority, long denied the rights of British citizens, but defence minister Denis Healey, now responsible for the troops on the streets, reminded his colleagues of the hard political realities: Protestants were the majority and “if we put the majority of the population against us, we should end up in a 1912-14 situation”.

He was referring to the period of the Home Rule crisis when ‘Carson’s Army’, rejecting the authority of Westminster, brought Ireland and Britain to the brink of civil war, resulting in partition and a unionist one-party state.

This warning from Healey, the son of an ardent Irish Nationalist, sank home with Harold Wilson and his cabinet. Unionist one-party rule, with its lack of vision and inclusiveness, would survive for the time

being.

Britain moved to assume control of security, now vested in the General Officer Commanding (GOC) Sir Ian Freeland, and Callaghan prepared to visit the north.

One thing was certain: after August 1969, things here would never be the same again.

:: Dr Éamon Phoenix is an historian, commentator and Irish News columnist. He is a member of the Taoiseach’s Expert Advisory Group on Centenaries