FOR the first time in our hour-long conversation, Rosemary Nelson suddenly seemed uncomfortable.

"The threats? Yes, there are threats. Particularly when I am involved in highlighting issues, when there is a lot of attention..."

The interview had focused on concerns for her clients, but now it veered into the widely publicised fears for her own safety.

"What type of threats? Well, death threats. Of course it’s frightening, when you have children and a husband. It has to have some impact on your life."

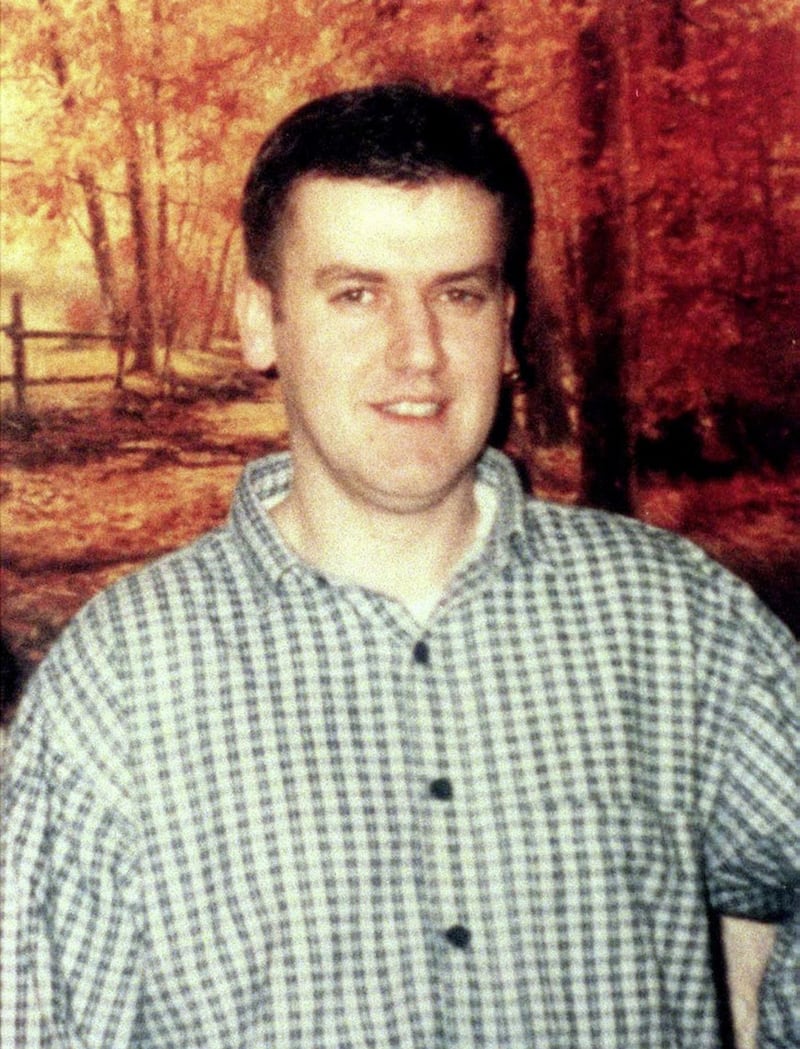

The 40-year-old solicitor was sitting in a plain upstairs room in her office: two chairs, a simple desk on hard-wearing carpet. Papers and files spilled in an arc in front of her. She sat with her legs curled, a cup of coffee clasped in her hands. "The thing is that it is so sinister..."

The phone to her right rang and she answered it. Minutes later a mobile in her bag buzzed for attention. A third telephone gave a muffled ring before she hunted it out beneath files to her left. Rosemary Nelson was a busy woman.

By then her killers were busy too. Their bomb would detonate under her car as she drove from the home she shared with her husband and three children in Lurgan, Co Armagh.

That day in her office she chatted about her family. She had a young daughter and two sons. The boys had left on a school ski trip and she talked about her worries for them. But such ordinariness made the wider picture seem all the more surreal.

She lived in an area dubbed the 'murder triangle' due to the sectarian violence seen around the towns of Lurgan, Craigavon and Portadown. Three cases there brought her to prominence.

The 1990s saw outbreaks of mass violence over controversial parades, with the most serious at Drumcree in Portadown, where Orange Order processions through the Catholic enclave of Garvaghy Road were opposed by the Garvaghy Road Residents’ Coalition. Rosemary Nelson became the coalition’s lawyer.

Prominent Lurgan republican Colin Duffy was jailed for the shooting of a former soldier in 1993, but he denied involvement and the murder conviction was quashed on appeal in 1996. His legal representative in the high-profile case was Rosemary Nelson.

In 1997 Catholic man Robert Hamill was walking home after a night out in Portadown when he was fatally injured in a sectarian attack, while witnesses claimed police were parked nearby. Rosemary Nelson championed calls for a public inquiry.

This all took place in an era of rising tension, when the hopes for peace were fragile and still beset by ongoing republican and loyalist violence. The course of events and her involvement in such prominent cases put her on the radar of violent loyalists and eventually set her at odds with the RUC.

United Nations Special Rapporteur Param Cumaraswamy met Rosemary Nelson and compared her situation to that of solicitor Pat Finucane, who was killed in 1989 by loyalists colluding with UK state forces.

In September 1998 Mrs Nelson testified at a hearing in the United States Congress in Washington: "I have begun to experience some difficulties with the RUC. These difficulties have involved RUC officers questioning my professional integrity, making allegations that I am a member of a paramilitary group and, at their most serious, making threats against my personal safety, including death threats."

Earlier in her life she had dealt with very different pressures. Her relatives would later explain that she was born with a large strawberry birthmark on one side of her face and from the age of 10 endured weeks at a time in a Scottish hospital for skin graft surgery that continued into her teens.

The surgery left extensive facial scars that loyalists later used for propaganda purposes. Leaflets were circulated that falsely attributed the scars to her being a former bomber. It was the beginning of a process that saw her life become public property, one which accelerated after her death.

Rosemary Nelson’s murder immediately sparked allegations that security forces colluded with her loyalist killers. The claims were strenuously denied but they attracted international attention and came as a special policing commission set up under the Good Friday Agreement was considering the future of the RUC.

Her case became part of the battle over the reputation of the predominantly Protestant police force and so her name was exalted by some and attacked by others. In the end, it had the effect of amplifying the calls for radical reform of policing. Was that her legacy?

As mourners left St Peter’s Church in Lurgan to lay her to rest, there was no talk of legacy. A funeral procession moves as one, speaking to itself in a low voice. Its many feet drag to a destination that it does not wish to reach. On that day there was also an air of disbelief at a death that was foretold and perhaps could have been prevented.

As the hearse turned the corner near her home, passing the spot where she died, huge crowds waited on either side of the road, like two human arms waiting to embrace the funeral cortege before melting into it. At the heart of the throng, a car carried a huddle of three confused children, cowering from the world.

But all this was yet to come.

Rosemary Nelson finished her phone calls. She brought the conversation back to her clients living on the Garvaghy Road. They included people whose homes were invaded by loyalist gangs at night. Families barricaded into bedrooms. Threats shouted up the stairs in the dark.

"I am a human rights lawyer," said Mrs Nelson, almost angrily. "I believe in the rule of law ..."

It was Friday March 12 1999. Three days later the bomb planted by loyalist paramilitaries would explode beneath her silver BMW. Rosemary Nelson was about to pay a terrible price for her work.

:: Steven McCaffery is former news editor of The Irish News. He now works for the Social Change Initiative, an international charity based in Belfast. This article appears in the book Reporting the Troubles, recently published by Blackstaff Press.