Dr Gladys Ganiel, who is writing a biography of Fr Gerry Reynolds and has access to his diaries and personal papers, says we can honour his legacy by achieving his radical vision of a united Church family

--------------

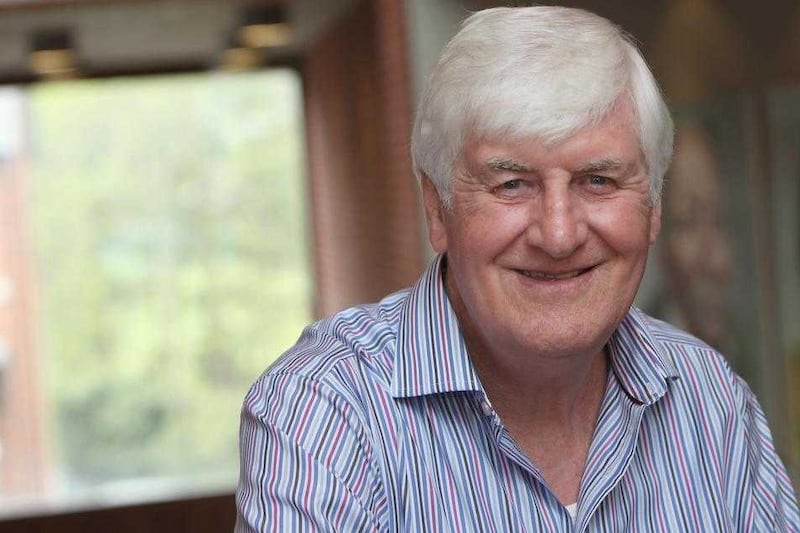

With his death on Monday, Father Gerry Reynolds, a Redemptorist priest based at Belfast’s Clonard Monastery since 1983, leaves behind a vision of the Church in Ireland that is worth working to make a reality.

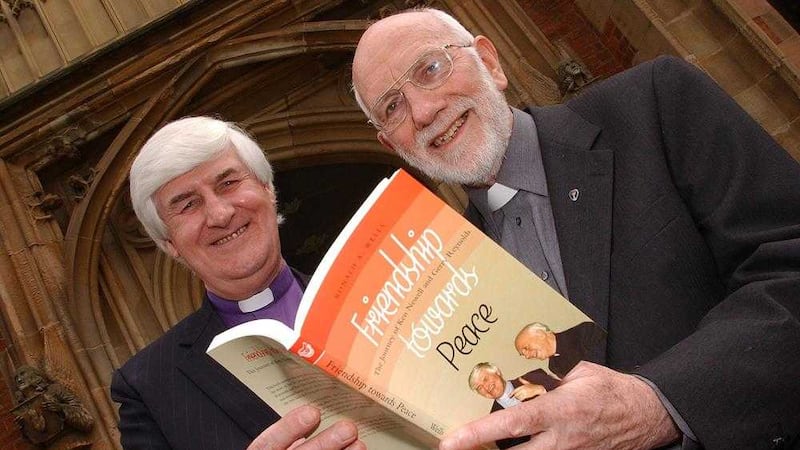

Fr Reynolds is best known for his role, along with the late Fr Alec Reid, in promoting dialogue during the Troubles.

While Fr Reid brokered behind-the-scenes peace talks between Gerry Adams and John Hume during the 1980s, Fr Reynolds provided support and acted as a confidant.

These talks – which were loaded with risk – are widely regarded as important precursors to the peace process.

Fr Reynolds also helped organise quiet dialogues among Sinn Fein politicians and Protestant clergy, which opened lines of communication and promoted understanding.

It is impossible to calculate the ripple effect of these Protestant clerics’ interactions with Sinn Fein when they returned to their congregations and their communities. But many were inspired to undertake cross-community and ecumenical work in their own ministries.

Fr Reynolds’ grassroots work with Christians from a range of traditions is where he devoted the bulk of his considerable energy during his time at Clonard, driven by a vision of the Christian Church in which divisions no longer exist.

When he said he saw Protestants as sisters and brothers in Christ, this was not just a theoretical idea inspired by the spirit of the Second Vatican Council – although Vatican II was important in shaping his formation as a young priest.

Rather, he chose to put ecumenical theory into action, worshipping alongside his Protestant sisters and brothers, developing pioneering ecumenical initiatives such as the Unity Pilgrims (a group of Catholics who worship at Protestant churches on Sunday mornings); the Clonard-Fitzroy Presbyterian Fellowship, which he developed along with Rev Ken Newell during the most difficult days of the Troubles; and the In Joyful Hope initiative, which promotes shared Eucharist/communion.

Fr Reynolds was also involved with the ecumenical Cornerstone Community, inter-faith dialogue, prison ministry, and ministry with Travellers.

While these ministries were often carried out quietly and without fanfare, they inspired others to reach out to those from the ‘other’ side.

Fr Reynolds’ work was sustained by a formidable spiritual discipline, including his regular prayer, devotion to the three persons of the Trinity, the nourishment he gained through his involvement with the Jesus Caritas Priests Fraternity, and the inspiration he drew from the witness of the nuns of the Little Sisters of Jesus.

In July, I began working on a biography of Fr Gerry Reynolds. I had begun interviewing him and reading his journals and assorted papers.

We had not yet discussed a title, but on hearing him described this week as having his `feet in the clouds', I may make this the title.

Over the years, this phrase was apparently used to denote scepticism at Fr Reynolds’ grand visions for Christian unity, inter-religious harmony, and peace. But I think if those who loved him and valued his work want to honour his legacy, they can strive for nothing less.

And what would that vision of the Church in Ireland look like? I want to let Fr Gerry speak for himself, drawing from some of his papers and homilies:

:: Change starts with you, not the other

"One evening in July 25 1985, with little enthusiasm, I joined a small group of Catholics and Protestants for a Bible study in Clonard Monastery. Our text was 2 Corinthians 5:11-21. This line jumped out at me: 'God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself, not holding anyone’s faults against them, but entrusting to us the message of reconciliation.'… I realised that every time I told stories about the other side, I did so holding their faults against them. My heart’s relationship with the Shankill people changed that Thursday evening."

:: Dialogue makes room for the Spirit of God to work among us

"Shortly after coming to live in Belfast, I asked… Fr Alec Reid what needs to be done to end the plague of political violence. I remember well his answer. The only way out is through dialogue with one another. Humanly speaking it’s impossible – but dialogue makes room for the Holy Spirit to work in the whole situation.

In the intervening years I have learnt from experience that dialogue can lead to an opening of hearts to one another and to the mutual understanding, respect and trust which are the foundation of true peace. I would now say: Dialogue is a new name for faith in the Spirit of God present in every person; it is a new name for the patient hope that sustains us in the long haul; it is a new name for love of one’s neighbour – and indeed of one’s enemy."

:: God is at work in our history

"I believe history is moving us towards this authentic encounter with God which will transfigure us – I deliberately use a religious word – and enable us to see one another no longer as a threat, but as companions at the family table and collaborators at the workbench of peace.

I live by conviction that the God of reconciliation is at work in history leading believers into inter-religious dialogue, the dialogue of peace. I try to identify what my responsibility to work with him means in practice. There is a right thing to do every day."

* Dr Gladys Ganiel is a research fellow in the Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice at Queen’s University Belfast