Margaret Thatcher bitterly resisted calls for a major public education campaign to counter the threat of an Aids epidemic, newly released government files reveal.

Papers released by the National Archives show how the then prime minister repeatedly raised objections, warning that alerting teenagers to the dangers of "risky sex" could backfire and cause "immense harm".

She only backed down after a series of stark warnings by advisers that hundreds of thousands could become infected by the Aids virus unless people - particularly gay men and drug users - were persuaded to change their lifestyles.

The first case of Aids in the UK was recorded in 1981 and by 1986 there was growing public awareness of the spread of the disease for which there was then no known treatment.

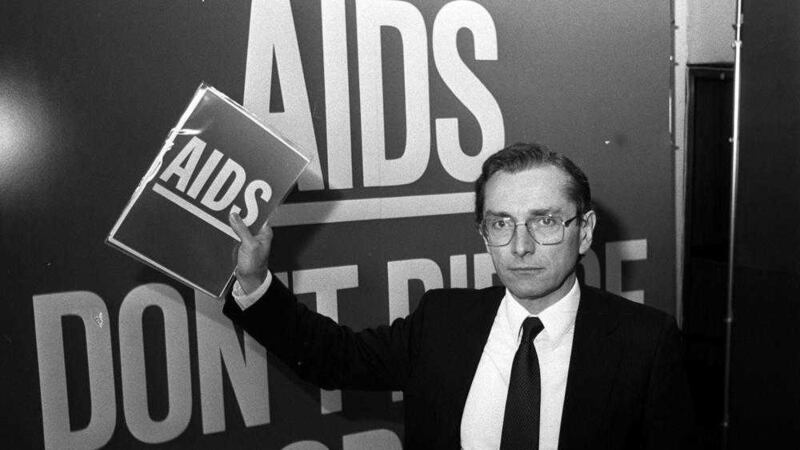

But when health secretary Norman Fowler proposed a newspaper advertising campaign setting out advice on "safe sex", Mrs Thatcher was horrified. In particular she objected to a section entitled "What is risky sex?"

"Do we have to do the section on risky sex?" she scrawled in a handwritten note. "I should have thought it could do immense harm if young teenagers were to read it."

She suggested the advert could even breach the Obscene Publications Act and proposed a more limited campaign based on previous public information campaigns on "venereal disease".

"I think the anxiety on the part of parents and many teenagers who would never be in danger from Aids, exceeds the good it may do," she wrote.

"It would be better in my view to follow the 'VD' precedent of putting notices in surgeries, public lavatories etc. But adverts where every young person will read and hear of practices they never knew about will do harm."

Mr Fowler, however, stuck to his guns, insisting that unless the advice was included - particularly in relation to gay men - the advert would lose "all its medical authority and credibility."

"Given that there is no vaccine and no cure, the only option open is public education," he informed her. "No one is condoning these practices - quite the contrary; but they exist and are one of the ways by which Aids spreads."

When deputy prime minister William Whitelaw told her there was no support for her objections among other ministers she was forced to give in.

Nevertheless, when Mr Fowler suggested following up the adverts with information leaflets sent to every home in the country she again dug in her heels - prompting a series of exasperated warnings that she was out of step with the public mood.

The cabinet secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, said that while there had only been 512 cases so far in the UK, experts estimated that 25,000 people could be carrying the disease unaware that they had been affected.

"If there is no change in habits and practices, particularly but not exclusively among those currently most at risk (homosexual and bisexual men and drug misusers), there could at the end of five years be half a million infected carriers of whom a substantial number would subsequently develop the disease; and that is a sober estimate," he wrote.

Bernard Ingham, her trusted press secretary, added: "There is certainly a feeling abroad that the Government is doing too little and is not treating the issue with sufficient urgency.

"There is also a feeling that the Prime Minister is acting as a brake on educational publicity."

Once again, she was forced to give way.