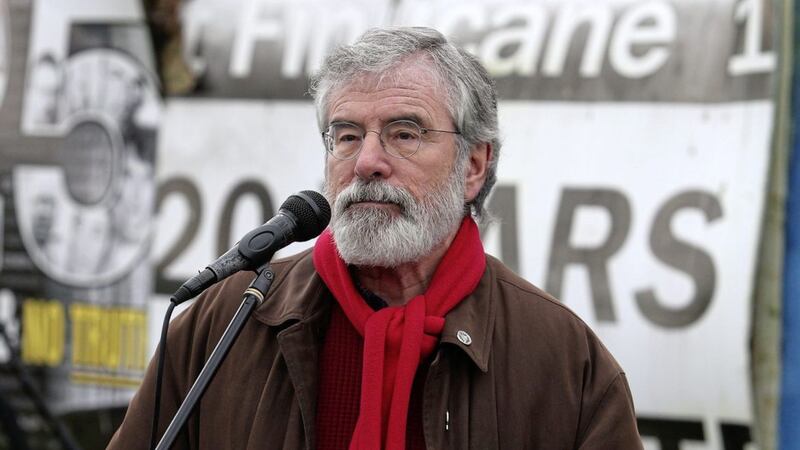

GERRY Adams is by no means the first to say it's necessary to plan for a united Ireland but arguably he's one of the most important voices to contribute to the debate. As the former Sinn Féin leader and many others have highlighted, Brexit has been an unmitigated disaster in terms of delivering a democratic decision.

The widespread belief that the Leave campaign had no chance of victory in 2016 meant the shape of a post-EU United Kingdom was never given serious consideration by the pro-European British government ahead of the referendum. Meanwhile, the Leave campaign's message was one of eternal optimism, an abstract notion of sunny uplands where we'd all live happily ever after freed from Brussels' shackles.

You'll not need reminding how things have turned out. Three years on, a largely pro-Remain Westminster parliament has been unable to give realisation to the will of the people in England and Wales, nor has it been able to quell the angst in Northern Ireland and Scotland, where people voted by an even greater majority to stay in the EU.

There may be many reasons for Mr Adams airing his argument at this juncture and it's likely Sinn Féin's recent poor electoral performance has prompted a degree of introspection. However, sometimes it's important to separate the message from messenger.

Laying the groundwork for a united Ireland is already underway. The Ireland's Future organisation, made up of a variety of figures from civic nationalism, is already examining the social, political and economic consequences of a 'Yes' vote in any forthcoming poll on unity. The irony that their work has been prompted largely by the mess around Brexit is not lost on the participants.

But while the contribution of civic nationalism is welcome and worthwhile, Mr Adams's call for the Dublin government to initiate a process that would comprehensively assess the implications and possibilities that would stem from majority support for a united Ireland, is valid – if not entirely original.

If nothing else it would clearly demonstrate that Leo Varadkar's nationalism is more than mere rhetoric and that he is standing over his pledge to never again abandon northern nationalists.

Perhaps the first thing that needs to be acknowledged in this process is that a united Ireland isn't inevitable and also that there are many differing interpretations of what unity would entail.

However, too often debates about who should do the preparatory work and how, escalate quickly into a discussion about the merits of a united Ireland versus the union.

What Mr Adams may be suggesting is that we park the debate about the best outcome for a while and instead focus on how it might come about and how the various outcomes that may arise from a border poll would look.

The work of the Citizens' Assembly in the south ahead of the abortion and divorce referendums has proved invaluable in laying out the arguments rationally and factually.

It makes obvious sense that a similar discussion about the route, or routes, to Irish unity begins in earnest.