Hume flew the kite further, that he would make his views known to the US Congress, to White House officials, and to the President himself later that week in Washington during the St Patrick’s Day celebrations.

When Hume got to Washington a few days later for St Patrick’s Day on 17 March 1994, he drove his point home to Clinton, who put great store in Hume’s judgements and political instincts.

Hume saw a chance to reinforce a shift in attitude within the IRA toward ceasing their violent campaign, which culminated in a series of fundamental breakthroughs later that year, when the IRA and the Combined Loyalist Military Command issued ceasefire statements, on 31 August 1994 and 13 October 1994, respectively.

Albert Reynolds in particular, in the role of Taoiseach, was also important in consolidating the IRA ceasefire.

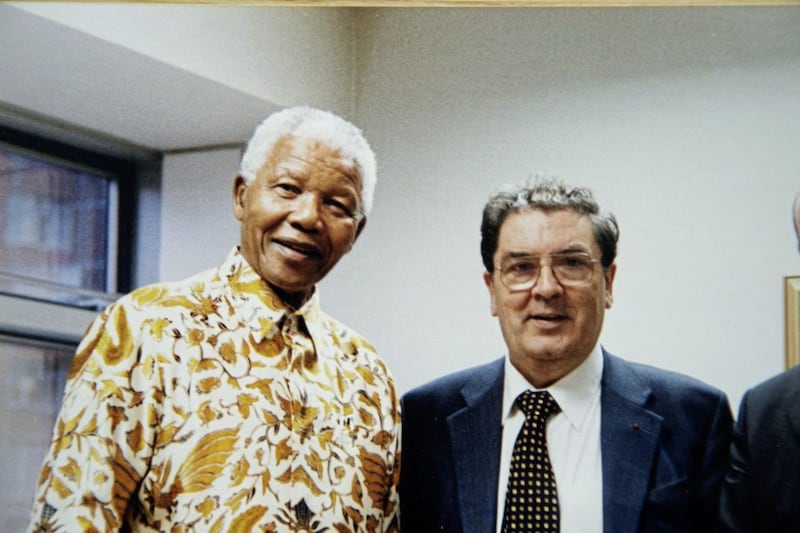

Iconic footage of Adams, Hume and Reynolds in front of the Department of the Taoiseach was intended to symbolise a new cooperation both across different strands of nationalism and across the border.

But, as Eamonn McCann argued at the time, it was necessary to include Hume in that photo, from a Republican point of view, since Sinn Féin was particularly sensitive to being seen to recognise the Taoiseach at the expense of their own claims to legitimacy: ‘the occasion might too easily have been seen as the Republican leadership formally relinquishing something which the Movement had always regarded as a core belief.

The inclusion of Hume made the picture presentable as three nationalist leaders conferring together, rather than one conceding legitimacy of leadership to another’.

These ceasefires also prompted Clinton to make good on his promise to send a special envoy to Northern Ireland. On 1 December 1994, Clinton announced the appointment of George Mitchell as Special Adviser for Economic Initiatives in Ireland.

While critics of Hume denounced his conferral of ‘legitimacy’ on Adams, he was also sharply aware of how important it was to properly handle that claim to legitimacy on the part of Sinn Fe?in; in a meeting with Boston Globe journalists and editors, Hume referred to the need for a referendum as the best way to address it:

John Hume, Northern Ireland’s leading moderate nationalist politician, renewed yesterday his call for a referendum of all Irish people on an end to violence and a commitment to multiparty peace talks ... ‘An unambiguous statement by the Irish people could have some sway over IRA extremists ... given one of the IRA’s theological foundations, that the last time the Irish people spoke was in 1918,’ Hume said in a meeting yesterday with Globe reporters and editors.

Hume, speaking on the Charlie Rose show on 21 March 1996, said:

‘The fact that [Adams] came to the United States was a very crucial and important step in the peace process and was one of the major factors that led to the cessation of violence ... and as a result of that cessation of violence, up to 400 people in Northern Ireland now [are] walking around alive who would otherwise have been dead ... [Given that] 20,000 soldiers in my streets and 12,000 armed policemen and the toughest security laws in Western Europe hadn’t stopped the killing throughout the 25 years, I felt that if I could save a single human life by direct dialogue, it is my duty to do so.’

What had prompted Hume to move from characterising the IRA’s approach in the early 1980s of a continued armed campaign in tandem with an openness to the political process as being ‘just blackmail.

All they want then is power’, through to ushering their way into politics? Sinn Fe?in members had gained mandates; the Anglo-Irish Agreement, the Hume– Adams dialogue had culminated in the joint Hume–Adams Statements, and the Downing Street Declaration.

All were building towards a moment when the IRA could no longer refute the validity of the political process and abandon their military campaign.

However, that discussion on arms decommissioning turned out to be an interminably long one, staggering on into the next millennium.

The issue of decommissioning hung as the Sword of Damocles over both the peace talks’ participants and those acting as guarantors that those negotiators with a history of violence would exclusively embrace constitutional means.

While the decommissioning debacle continued, Bill Clinton made the decision to become the first sitting US president in history to visit Northern Ireland.

(Clinton first visited London and in his public statements championed the need for courage and taking risks in good faith. Poignantly he referred to the former Prime Minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin, who had been assassinated for taking such risks.)

During his historic trip to Derry, on 30 November 1995 Clinton put down a marker for Hume’s work dating from the 1960s: ‘Hillary and I are proud to be here in the home of Ireland’s most tireless champion for civil rights and its most eloquent voice of non-violence, John Hume.

I know that at least twice already I have had the honor of hosting John and Pat in Washington. And the last time I saw him I said, ‘You can’t come back to Washington one more time until you let me come to Derry’. And here I am.’

After the euphoric scenes in Derry, a winter of discontent was marked and marred by the IRA breaking their ceasefire. The Irish, British and American governments sustained their efforts to secure peace.

On the following St Patrick’s Day, in 1996 in the White House, Taoiseach John Bruton affirmed, in both language and strategy deriving from Hume’s formulations, that the goal remained ‘a comprehensive agreement, not an internal settlement within Northern Ireland, a comprehensive settlement dealing with the relations between Britain and Ireland, dealing with relations between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland.

What we’re aiming at in that three-stranded approach is a system of government for the people of Northern Ireland to which both communities can give equal allegiance’.

Bruton maintained that the issue of decommissioning should not be allowed to derail the peace process, which to some observers meant that it had been deprioritised.

Decommissioning was therefore becoming hugely symbolic of anxieties on both sides: the IRA feared to be seen as surrendering, while those on the opposite side of the conference table feared conceding anything to the political wing of a still armed terrorist organisation.

While Clinton’s commitment to a tiny pocket of the earth was dramatic, his engagement was not always welcomed.

There were elements of Clinton’s involvement with Northern Ireland that Ulster Unionists found unpalatable, particularly at the outset.

In an adept act of diplomacy on Bill Clinton’s part, he invited all strands of Northern Irish political life to the White House and encouraged them to think of it as a space where Northern Ireland’s cultural pluralism could co-exist.

David Trimble recalls dressing in tartan and singing Ulster Unionists songs in the White House, which helped to create a new view of Bill Clinton among Unionists:

The Unionist community viewed Clinton with a great reserve, which Clinton was aware of, and in his very first visit here, in the speech that he delivered early in the morning in which he told Republicans ‘you’re the past, not the future’, and addressed them in very unequivocal terms.

That actually changed the Unionist outlook on him, and is the reason why that evening at the City Hall in Belfast he had a huge crowd.

Decommissioning remained a very complex issue and had deep implications for the sovereignty of both Britain and Ireland. The sovereign governments of Britain and Ireland were fully committed to peace negotiations, now chaired by Senator George Mitchell, but they were led by political parties.

In the revolving doors of political leadership, the representatives of the two governments were anxious to stamp their seal on history by negotiating the deal.

This urgency unwittingly lent Sinn Fe?in a time advantage, and strengthened their hand when they procrastinated on decommissioning.

Seamus Mallon remembers:

‘The reality is that the two sovereign governments, Irish and British, had a responsibility for forty years to protect the people of this island from those who held illegal arms for subversive reasons.

They did not get those arms. Why, with all the intelligence that exists nowadays, were those arms dumps not dealt with?

Way before the arms becoming an issue in a political process, they were a governmental problem.

Only the two governments had the authority to deal with them [illegal arms], but here you had a situation where the governments were actually using the developing political process to solve problems which were not a remit of the new Assembly or the new political process, almost where the governments actually use the creation of a political system to solve the problems for which they are responsible’.

Mallon’s argument is that the peace process elevated former terrorists to the status of legitimate mainstream politicians.

He suggests that the process made Sinn Fe?in almost as a legitimate governmental entity in its own right, rather than as a subsidiary agent within a negotiating process in which two sovereign governments granted them an opportunity to leave behind their violent and illegal past actions and fully participate in politics.

Mallon implies that in the course of the peace process, the two sovereign governments should have seized the IRA arms to demonstrate their own primacy and sovereign authority.

From 1997 to 2001, Canadian diplomat John de Chastelain was Chair of the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IIDC) and in 2000, two high profile international figures, Martti Ahtisaari, former president of Finland (1994– 2000), and Cyril Ramaphosa, South African businessman and politician, inspected IRA arms dumps and reported to the IIDC.

This ritual of decommissioning, overseen by international observers, gave a degree of legitimacy to Sinn Fe?in–IRA, allowing them progressively to rewrite the narrative of the Troubles, which still continues apace.

One source concedes that there was an element of bilateralism in official dealings with Sinn Fe?in and the IRA, who had arguably been the decisive and primary motor of instability in Northern Ireland over thirty years.

They thus became primus inter pares among the groups with whom Senator Mitchell had the responsibility to consult.

On a number of occasions, the two governments directly negotiated with Sinn Fe?in. However, the IRA, impatient with the British government and indignant that the decommissioning of weapons was a precondition for their entry into talks, resumed their violent campaign on 9 February 1996.

Speaking at a news conference on 29 May 1997, Clinton’s impatience with the violent campaign was beginning to form into an ultimatum to the IRA: ‘Obviously, I think that Sinn Fe?in should participate in the talks.

And I think the IRA should meet what I think has to be the precondition.

You can’t say, “We’ll talk and shoot; we’ll talk when we’re happy and shoot when we’re not.’

The thinly veiled threat to Sinn Fe?in was clear; their charmed position as the political wing of an organisation carrying out bomb attacks was becoming less and less tenable, and the parameters within which it could operate were contracting.

Clinton’s pressure worked.

Six weeks later, the IRA met the condition Clinton had made, and on 19 July 1997, Clinton welcomed the second IRA ceasefire ‘on behalf of the American people’.

Now the conditions precedent had been fulfilled, it was time for the most gruelling part of the journey to begin: the all-party talks in Northern Ireland, chaired by George Mitchell, overseen by the Irish and British governments, and supported at every turn by the US President.

* Extract taken from John Hume In America: From Derry to DC by Maurice Fitzpatrick, who is also the director of the accompanying film In the Name of Peace which is now showing at cinemas across Ireland.