THE horrors of an incident remembered as one of the sparks that lit the fire of the Troubles have been recalled publically for the first time by a former civil rights campaigner, who still feels “betrayed” by police who allowed him to face the sectarian wrath of baying loyalists intent on violence.

Liam Andrews is a prominent Irish language activists in west Belfast, but in 1969, the then 21-year-old student was a keen proponent of the civil rights movement, having spent his teenage years running a gauntlet of hate on the Springfield Road, where his family lived in constant fear of being forced from their home by loyalists.

His experiences in a city divided by religious hatred prompted him to join a march from Belfast to Derry in January 1969 that would go down in history as a shocking example of a biased police force.

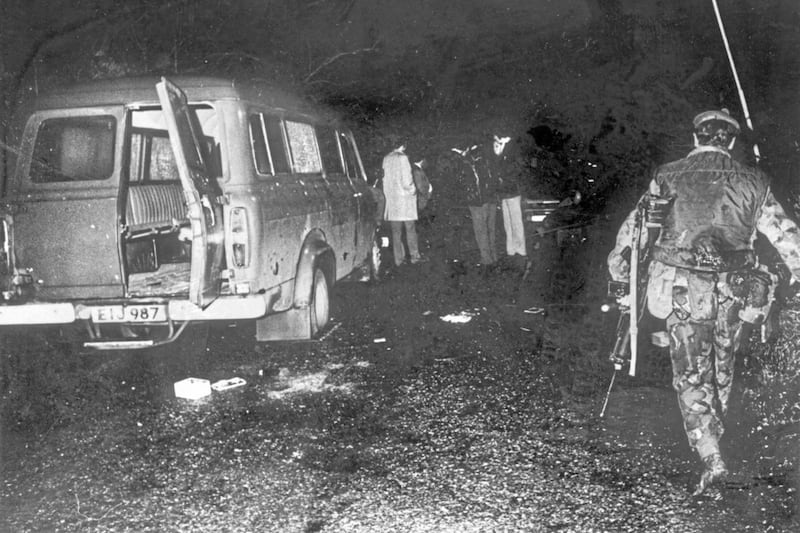

As the march passed Burntollet Bridge in Co Derry on January 4, participants came under attack from loyalist supporters of Ian Paisley, who had demonised the civil rights campaign as a front for militant republicanism.

The march that day was not sanctioned by the official NI Civil Rights Association – which in fact advised against it due to the political climate – but was instead headed by the Peoples Democracy movement.

Leading the loyalists was Paisley’s political allay and former British Army Major, Ronald Bunting, who was intent on disrupting the march as much as possible on its route between the north’s two main urban areas.

Infamously, RUC officers did nothing to protect the marchers from loyalists, who hurled rocks and were armed with makeshift weapons including nail-spiked cudgels.

Then a student at Queen’s University Belfast, Mr Andrews managed to escape Burntollet by taking shelter under the riot shield of an RUC officer as chaos ensued around him.

He was urged by campaigners afterwards to submit his recollection of events that day to form part of a detailed report on the attack and the police response – or lack of.

However, after making his statement, Mr Andrews withdrew it from publication, for fear it could leave his family at risk of further attacks by loyalists who were already on the verge of a pogrom that would eventually begin later that year and lead to the arrival of British soldiers in the north.

Although no-one lost their life as a result of the pre-planned attack in Burntollet, it demonstrated that loyalist violence against Catholics – even when carried out in front of police – could go unpunished.

It is estimated that up to 100 off-duty ‘B-Specials’ – members of the Ulster Special Constabulary – were among the mob keen to put the Catholic marchers in their place.

Mr Andrews said policemen and the loyalists were “ignoring one another’s existence”.

Things turned ugly, as Mr Andrews recalls: “I was attacked by a huge Paisleyite with a piece of tree, and he shouted ‘why don’t you fight, you fenian b***ards?’”

On the RUC response, his account reads: “He met with no resistance.”

As the attack grew in intensity, Mr Andrews and several other marchers grabbed an officer and “used him as a shield”, cowering under his riot shield which was “bombarded with stones and bottles”.

He continued: “The policeman remained as motionless as a statue, with his shield in the air. We moved him down the road in this manner for a distance of about 10 yards, then we abandoned him.”

The young academic was looking for a reaction from the RUC officers whose duty it was to protect those under attack.

“At no time did I see the police use violence against the Paisleyites, or baton charge them. When we got through safely we asked the police who were standing around to go back and help the others. They refused.”

Mr Andrews and fellow marchers managed to escape the violence at Burntollet, only to face further bile when the remainder of the procession entered Derry city and were pelted with rocks by loyalists.

“What do you expect me to do?” was the alleged response of an RUC officer who emerged from a vehicle Mr Andrews forced to stop by standing in front of it.

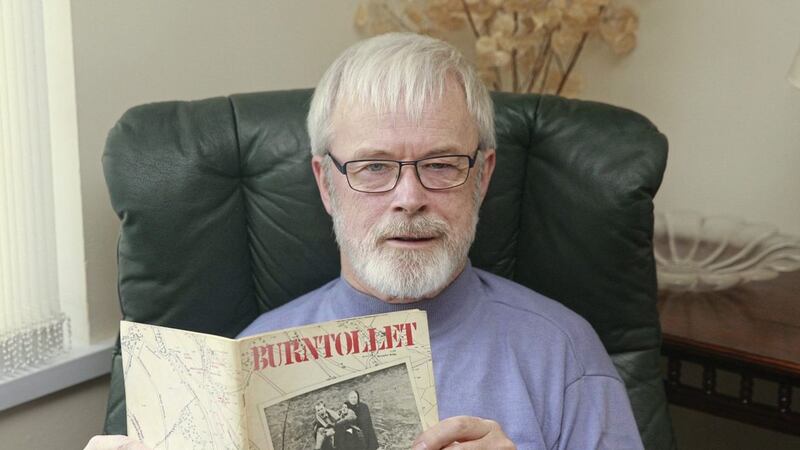

His account was due for publication in the 1969 book, titled simply ‘Burntollet’, authored by Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack that outlines the events of the day and the aftermath.

Fear of further reprisals against his then-family home at Springfield Road made him withhold it at the last minute, but the Andrews eventually packed a trailer full of belongings and fled in February 1972 after members of a loyalist ‘Tartan Gang’ attacked his sister in the street, and later told the family if they did not leave within hours, they would return to “finish you off”.

Speaking almost 50 years after Burntollet, Mr Andrews said his experience at the time opened his eyes to why some chose the path of conflict as a response to sectarian hatred against their community.

“That path was not for me, and I decided I would protect my identity by embracing my Irish culture through language and community activism,” he said.

“To this day there are people who claim the Civil Rights marchers were manipulated by violent republicanism or were mistaken in their beliefs. We were nothing of the sort – we were full of optimism and there was a real attitude of ‘let’s change society’.

“We were perfectly entitled to do this, but that day the RUC allied themselves with the worst of loyalism.

“We were depending on the police for protection, and instead they betrayed us.”