IRELAND'S early population may have come to the country from as far away as the Middle East and Eurasia, a genetic study has found.

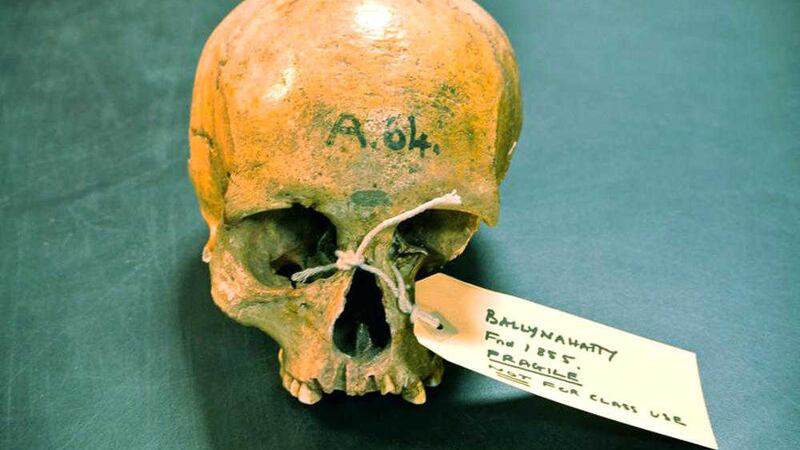

Scientists made the discovery after mapping the DNA of a farmer woman who lived near Belfast 5,200 years ago and three Irish men dating back to the Bronze Age around 4,000 years ago.

All the genetic sequences showed clear evidence of "massive migration", the researchers said.

The woman had ancestry that could be tracked to the Middle East, where agriculture was invented. About a third of the men's ancestry led to the Pontic Steppe, a huge region of flat grassland extending from the Danube estuary to the Ural mountains.

It was here that the horse was first domesticated, and chariots developed.

In much more recent times, the Irish have become famous for putting down new roots around the world in countries such as the US and Australia. The new research suggests that they themselves started out as immigrants.

Professor Dan Bradley, from Trinity College Dublin, who led the study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, said: "There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe and we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island.

"This degree of genetic change invites the possibility of other associated changes, perhaps even the introduction of language ancestral to western Celtic tongues."

The early farmer had black hair, brown eyes, and resembled southern Europeans, said the researchers.

But the three Bronze Age men from Rathlin Island had genetic variants for blue eyes and the most common Irish Y chromosome type.

They also had a genetic mutation associated with an excess iron disorder, haemochromatosis, so frequent in people of Irish descent that it is sometimes referred to as a Celtic disease.

Co-author Dr Lara Cassidy, also from Trinity College, said: "Genetic affinity is strongest between the Bronze Age genomes and modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh, suggesting establishment of central attributes of the insular Celtic genome some 4,000 years ago."