An “unexpected” discovery of tiny metal deposits in their native form in the human brain has raised hopes of potential new therapies for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

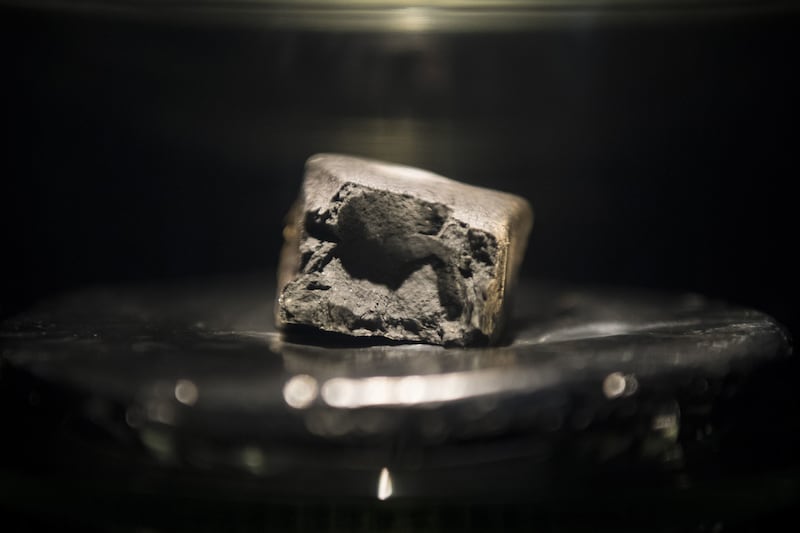

An international team of researchers, led by experts at Keele University, have found nanoparticles – around 1/10,000th the size of a pinhead – of elemental copper and iron within the brains of two deceased people with Alzheimer’s.

Metals can occur naturally in the body and are vital for health but they are usually stored as compounds, in oxidised forms.

The researchers said this is the first time elemental metals – metals in their native state – have been confirmed in human brain tissue.

Neil Telling, professor of biomedical nanophysics at Keele University, told the PA News agency: “The discovery of these elemental metallic particles in the brain tissue we studied was very much unexpected.”

The researchers said their findings, published in the journal Science Advances, could help scientists better understand whether elemental metals may be contributing to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and could, in future, facilitate “the development of new therapies to restore metal balance in diseased brains, potentially slowing or preventing the progression of these currently incurable diseases”.

Scientists used intense X-ray beams at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron facility in Harwell, Oxfordshire, as well as the Advanced Light Source facility in California, to identify elemental copper and iron in the human brain.

These metals were found in “plaques” containing harmful proteins, known as amyloid, which are linked to Alzheimer’s disease and usually accumulate in the spaces between nerve cells.

Copper and iron were discovered in “chemically reduced states”, including various ionized (where an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge) as well as elemental forms.

In these states, metals can produce harmful free radicals – unstable atoms which are toxic to brain cells.

Metal imbalances have previously been linked to the development of dementia and neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

However, Prof Telling, who is one of the authors on the paper, said there is “absolutely no reason to think that everyday exposure to these metals could cause their presence in the brain”.

He told PA: “In fact, it is not yet clear whether such particles are indeed linked to disease.

“At the very least their presence indicates that there is much more to learn about the way in which metals are processed in the brain.”

Prof Telling added: “It will take considerably more time and further research before this (the findings) could impact on treatments for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, for example, by answering ongoing questions regarding how metals interact with the amyloid proteins that the plaques are formed from.

“Ultimately, this line of research could lead to new treatments that target metals as well as the amyloid proteins currently under consideration.”

There are around 850,000 people with dementia in the UK, which is projected to rise to 1.6 million by 2040, according to Alzheimer’s Society.

Dr James Everett, postdoctoral research associate at Keele University and lead author on the paper, said that if magnetic metals identified through their research is linked to the development of Alzheimer’s, they have a potential use as bio-markers for disease diagnosis – using techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

This would allow for pre-clinical disease screening of at-risk cohorts, he added.

The research was funded by the UK Research and Innovation’s (UKRI) Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.