The fearsome tyrannosaurus rex bit through bone by keeping a joint in its lower jaw steady like an alligator, rather than flexible like a snake, a new study suggests.

Researchers say the finding over the famous carnivorous dinosaur sheds new light on a mystery that has puzzled palaeontologists.

Dinosaurs had a joint in the middle of their lower jaws, called the intramandibular joint, which is also present in modern-day reptiles.

Previous research suggested this joint was flexible – like in snakes and monitor lizards, helping carnivorous dinosaurs to keep struggling prey in their jaws.

However, it has been unclear whether the jaws were flexible at all, or how they could be strong enough to bite through and ingest bone – which T. rex did regularly, according to fossil evidence.

John Fortner, a doctoral student in anatomy at the University of Missouri and the lead author of the study, said: “We discovered that these joints likely were not flexible at all, as dinosaurs like T. rex possess specialised bones that cross the joint to stiffen the lower jaw.”

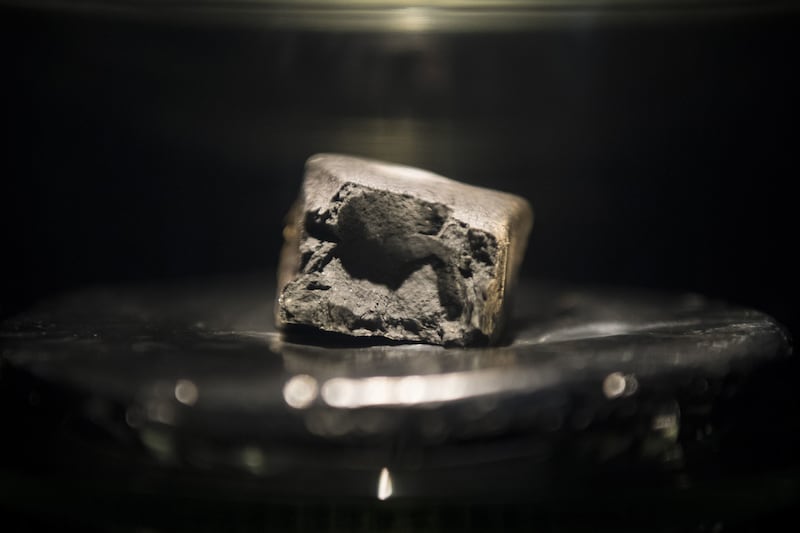

Researchers used CT scans of dinosaur fossils and modern reptiles to build a detailed 3D model of the T. rex jaw.

Their simulations included bone, tendons and specialised muscles that wrap around the back of the jaw, or mandible, which previous studies did not.

Mr Fortner said: “We are modelling dinosaur jaws in a way that simply has not been done before.

“We are the first to generate a 3D model of a dinosaur mandible which incorporates not only an intramandibular joint, but also simulates the soft tissues within and around the jaw.”

The research is presented at the American Association for Anatomy annual meeting during the Experimental Biology (EB) 2021 meeting, held virtually from April 27 to April 30.

To look at whether the intramandibular joint could maintain flexibility under the forces required to crunch through bone, the team ran a series of simulations to calculate the strains that would occur at various points depending on where the jaw hinged.

Their findings suggest bone running along the inside of the jaw, called the prearticular, acted as a strain sink to counteract bending at the intramandibular joint, keeping the lower jaw stiff.

Mr Fortner added: “Because dinosaur mandibles are actually built so much like living reptiles, we can use the anatomy of living reptiles to inform how we construct our mandible models.

“In turn, the discoveries we make about T. rex’s mandible can provide more clarity on the diversity of feeding function in today’s reptiles, like crocodilians and birds.”