Climate change is undoing decades of knowledge on safeguarding coral reefs by fundamentally changing the structure and composition of its ecosystems, scientists have said.

Over the years, repeated coral bleaching due to warming seas has caused disruption to marine ecosystems around the world.

This, in turn, has reduced the availability of food and shelter for many marine species that rely on these coral structures, resulting in huge biodiversity losses.

The phenomenon has also affected protected areas known as marine reserves, which are the “delicate and vital ecosystems” scientists have been using as a guide to rejuvenate biodiversity in other disrupted regions.

In a study published in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers said conservationists may have to rethink the role of these reserves.

Lead author professor Nick Graham, of Lancaster University, said: “Climate change is so fundamentally changing the structure and composition of coral reef ecosystems, that the way the ecosystem functions and responds to common management and conservation approaches needs to be carefully re-evaluated.

“The rules we have come to rely on, no longer apply.”

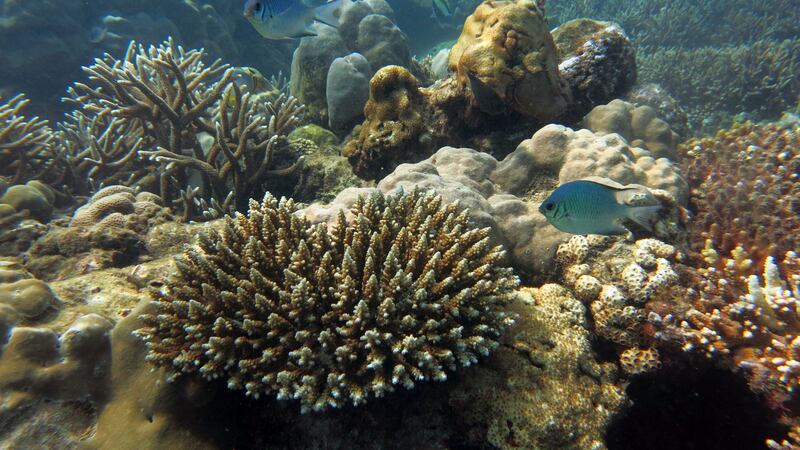

Bleaching occurs when seas become too warm, causing corals to shed colourful algae.

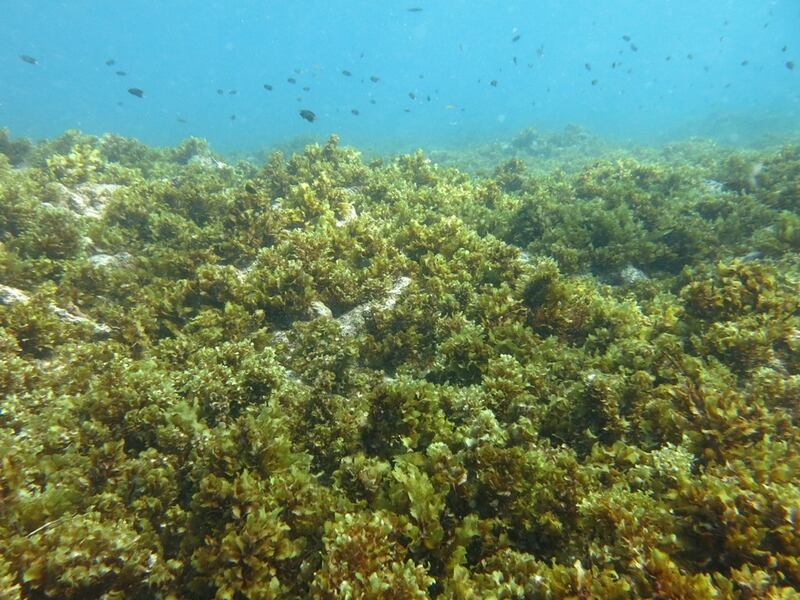

While some coral reefs are able to recover over time, others become dominated by seaweed.

The scientists focused on the coral reefs in Seychelles which were affected by a bleaching event in 1998, when around 90% of the coral died.

Scientists used data from 21 reefs spanning more than two decades to examine how reefs have changed over time and how it has affected the role of marine reserves.

Prof Graham said: “Our long-term records of Seychelles’ coral reefs show that before the bleaching event marine reserves contained high coral cover, a very biodiverse range of fish, and high biomass of carnivorous and herbivorous fish.

“Following the bleaching event, the role of the marine reserves changed substantially.

“They no longer supported higher coral cover compared to adjacent fished areas, and their role in enhancing biodiversity decreased.”

He said plant-loving fish, such as rabbitfish and parrotfish, dominated within the fish communities in the reefs.

But the findings showed these reserves have not been as effective at protecting the carnivorous predators, such as grouper and snapper species, which are nearer the top of the food chain, the researchers said.

The researchers attribute the predator population drop to less prey being available following the loss of coral reef structures.

However, the experts added that despite these climate-driven changes, the protected areas still have a role to play in ocean conservation.

Gilberte Gendron, of the Seychelles National Parks Authority, said this is because these reserves still protect higher levels of fish biomass of species that are important to local fisheries, when compared to openly fished areas.

He added: “For example, the protected herbivorous fish can spill out into openly fished areas and help support adjacent fisheries.”