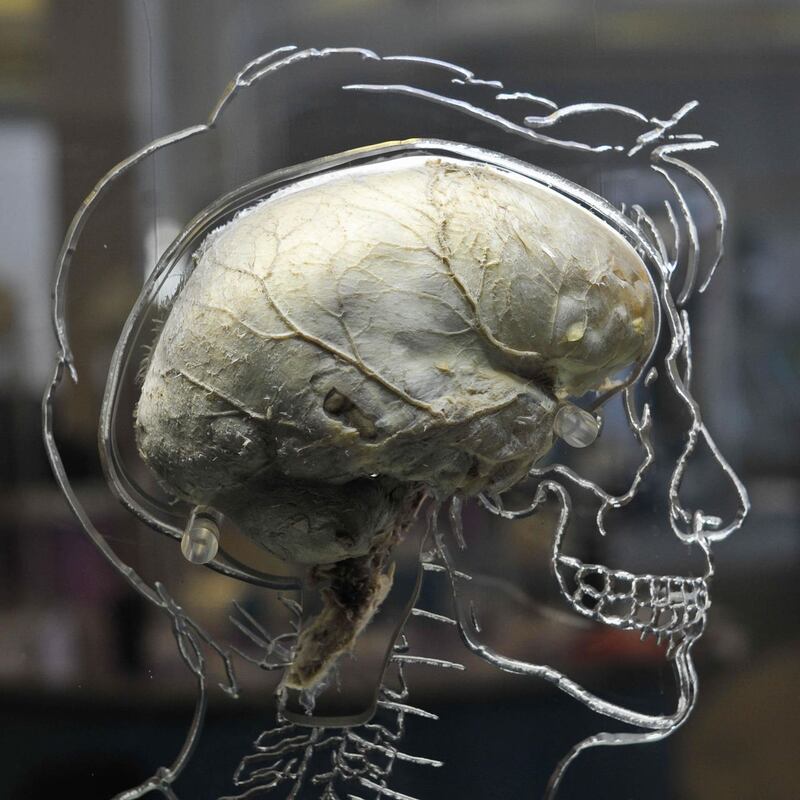

Severe childhood deprivation may cause long-term changes to the size and structure of the brain, according to new research.

Scientists found the brains of Romanian young adults, who were institutionalised and experienced childhood neglect in their home country, were around 8.6% smaller than those of their English counterparts who did not suffer childhood deprivation.

The team, which included researchers from King’s College London, also found that longer time spent neglected in orphanages was associated with a smaller total brain volume.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings Of The National Academy of Sciences, is the first to investigate the impacts of severe early childhood deprivation on the brain structure of young adults.

The research is part of an ongoing scientific project which started running in 1990 called the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA), involving a random sample of children from Romania and England who were later adopted.

The Romanian participants in the study had suffered severe childhood deprivation, were often malnourished and had minimal social contact and little stimulation before being adopted into nurturing families in the UK.

Previous research involving the same cohort has linked mental health, low IQ and greater attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms with childhood deprivation.

In the most recent study, researchers analysed brain scans of 67 participants from the Romanian group, aged 23 to 28.

They then compared these brain scans to those of 21 English adoptees of a similar age range.

The team found that the longer the time the Romanian adoptees spent in the institutions, the smaller the total brain volume, with each additional month of deprivation associated with a 0.27% reduction in total brain volume.

Statistical analysis showed that changes in brain volume related to deprivation were also associated with lower IQ and ADHD symptoms in the Romanian adults.

The researchers also found that the young Romanian adults had “markedly smaller right inferior frontal regions of the brain both in terms of volume and surface area”, compared to the UK adoptees.

In contrast, the brain’s right inferior temporal lobe was larger in volume and surface area and thickness for the Romanian young adults, which the researchers said was associated with lower levels of ADHD symptoms.

This implies that the increase in volume and surface area in this region may play a compensatory role in preventing development of ADHD symptoms, the researchers added.

Professor Mitul Mehta, from King’s College London’s Centre for Neuroimaging Sciences and neuroimaging lead for the study, said: “We found structural differences between the two groups in three regions of the brain.

“These regions are linked to functions such as organisation, motivation, integration of information and memory.

“It’s interesting to see the right inferior temporal lobe is in fact larger in the Romanian young adults and that this was related to fewer ADHD symptoms, suggesting that the brain can adapt to reduce the negative effects of deprivation.”