Being poisonous is a pretty great evolutionary trait for frogs to develop, but for that to work they need to be resistant to their own weapon.

Now a group of researchers has discovered how frogs don’t poison themselves with one particular toxin, despite the fact that it is almost identical to another chemical that is essential for normal function.

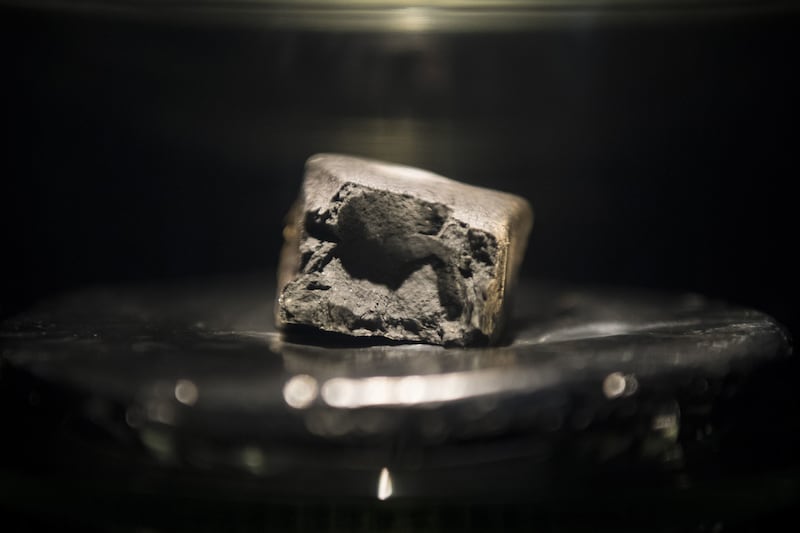

These tropical frogs use the toxin epibatidine, which targets the nervous system and causes seizures and death in predators that make the mistake of trying to nibble at them.

The chemical binds with a receptor in the predator’s body, like a key in a lock, signalling a lethal cascade of effects.

Most animals have the receptor because it’s the target of a non-poisonous chemical which is needed for learning and memory. But the poisonous version of the key floods the receptors and rather than helping memory, signals for a toxic chain of events.

These receptors, composed of thousands of amino acid building blocks, are also present in the frogs, so why don’t frogs poison themselves?

Well, scientists at Texas, St John’s and Stanford universities have found that the frogs have a genetic mutation which means those receptors differ by just three of their 2,500 component amino acids.

This minor change stops the toxin binding, meaning they’re resistant to their own poison. But what’s even more impressive is that the modified receptor still works for the essential chemical.

A co-author on the paper, Rebecca Tarvin, said: “Our work is showing that a big constraint is whether organisms can evolve resistance to their own toxins.”

And this research could help humans, since the equivalent receptor inside us affects nicotine addiction and pain.

A collaborator from the Texas alcohol and addiction research department, Cecilia Borghese, said: “Every bit of information we can gather on how these receptors are interacting with the drugs gets us a step closer to designing better drugs.”