Tiny potato granules dating back about 10,900 years have been discovered embedded in ancient stone tools in the US.

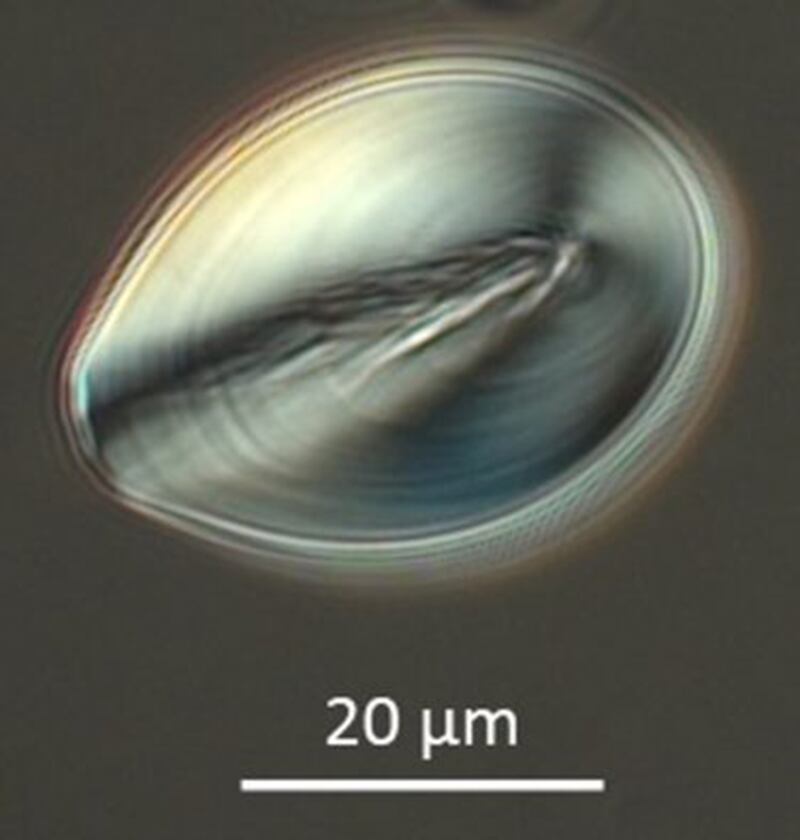

According to the researchers, these “well-preserved starch granules” are the oldest evidence of cultivation of the Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii) in North America.

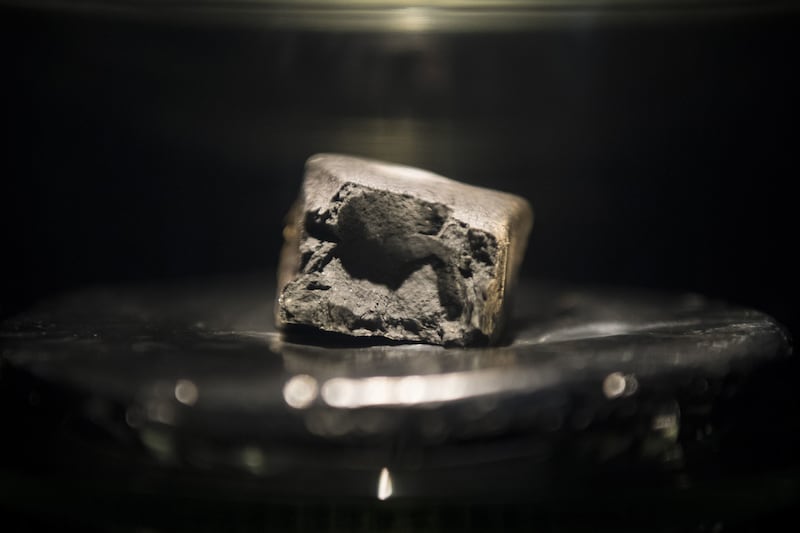

The tools, found in Escalante, Utah, were believed to have been used by ancient humans living in the region for preparing meals.

The Four Corners potato featured in the diets of several Native American tribes, including the Apache, Navajo and Hopi.

The archaeologists believe the species was transported, cultivated and possibly domesticated as the plant only grows in sparse, isolated populations near archaeological sites in Utah.

Modern potatoes eaten around the world today are not descendants from Solanum jamesii but rather another species known as Solanum tuberosum, which was domesticated in the South American Andes more than 7,000 years ago.

The researchers examined large sandstone slabs called metates and handheld grinding stones called manos, which were used in meal preparation.

They found microscopic starch granules that previous archaeologists never suspected were present.

“Grinding plant tissues with manos and metates releases granules that get lodged in the tiny cracks of stone, preserving them for thousands of years,” said professor Lisbeth Louderback, an archaeologist at the Natural History Museum of Utah and lead study author.

“Archaeologists can retrieve them using chemicals, modern microscopy and advanced imaging techniques.”

Researchers say the discovery could help us make the potatoes of today more resistant to drought and disease.

“This potato could be just as important as those we eat today, not only in terms of a food plant from the past, but as a potential food source for the future,” Louderback added.

The researchers want to mine its DNA to look for genes resistant to drought or disease to diversify our current potato crops.

“It’s hard to persuade the general public to care about rare plants,” said Bruce Pavlik, director of conservation at Red Butte Garden and study co-author.

“But this one has a real history associated with native people, with pioneers, with folks living though the depression and with the residents in Escalante today. Across the range, it should be treated as an antiquity, in a sense.”

The research is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.