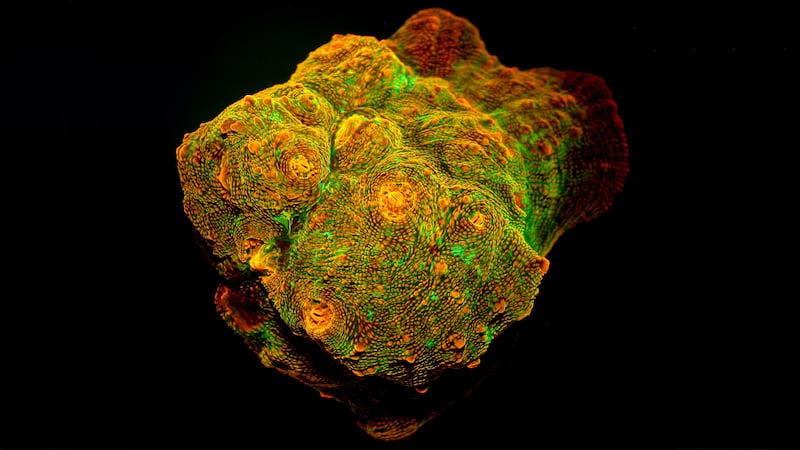

Some deep-water corals are fluorescent and scientists have finally figured out why.

Researchers from the University of Southampton’s Coral Reef Laboratory have found that corals in living deep water glow for the benefit of symbiotic microorganisms that help them thrive.

Corals have a mutually beneficial relationship with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae.

The tiny algae live inside the corals for shelter, carbon dioxide and nutrients while in return, the corals get photosynthetic products that can provide them with up to 90% of their energy needs.

This symbiotic relationship is important because sunlight is a key resource the corals need to survive and there is very little of it available in deep water.

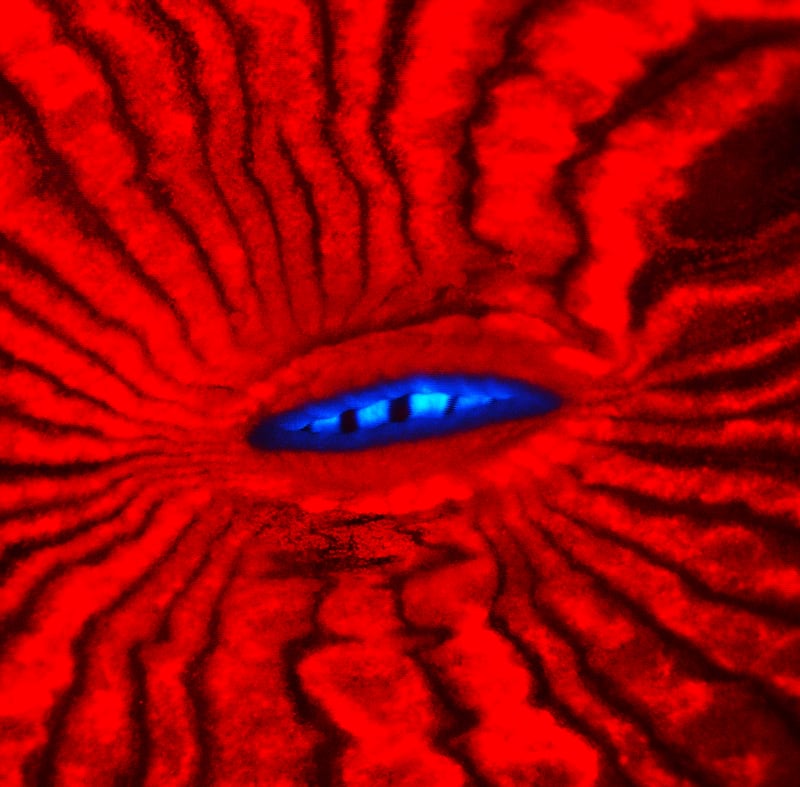

In fact, the little light that reaches these depths is almost all in the blue spectral range.

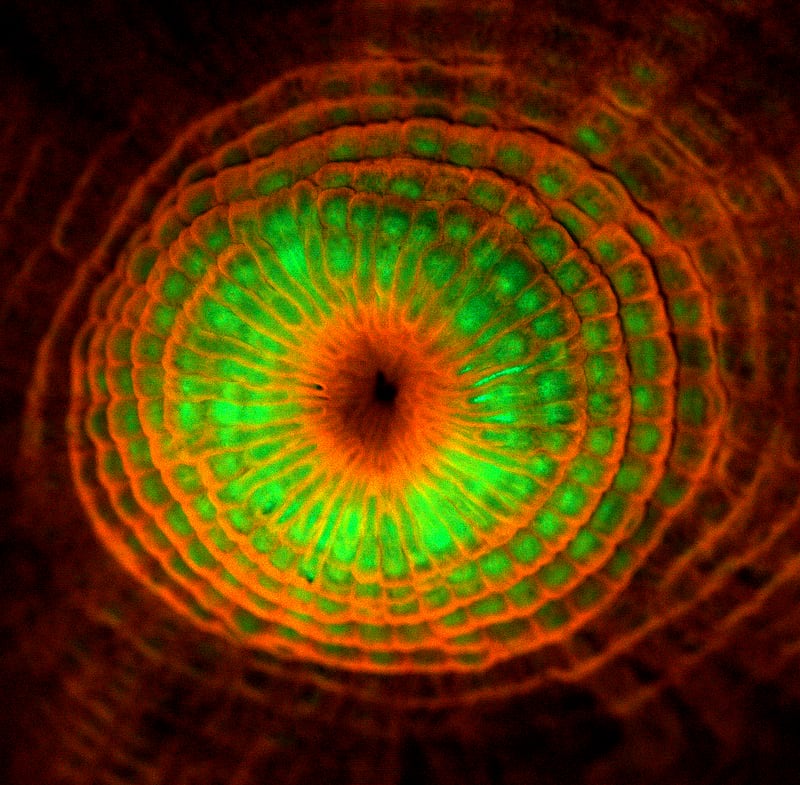

“These corals have a special type of fluorescent protein that when you shine blue light on it, re-emits it as orange-red light,” said Professor Jorg Wiedenmann, head of the Coral Reef Laboratory.

“What we showed is that these wavelengths help the symbiotic algae that live inside the corals thrive at the low-light levels.

“And that allows the corals to survive at greater depths.”

This orange-red light, the researchers say, has the potential to penetrate deeper into the coral’s tissue to help with the photosynthetic capacity of the zooxanthellae.

“Some of them are fluorescent while others are not,” said Prof Wiedenmann. “And the ones that are fluorescent, they invest a lot of energy in becoming colourful and these colours than then fulfil certain functions.”

Some corals living in shallow waters also show fluorescent properties but for a completely opposite reason – protecting the symbiotic species from the sun’s intense rays.

“In shallow waters they act as sunscreen to symbiotic algae and in deep water they help symbiotic algae to make better use of the small amount of light that is available at that depth,” said Prof Wiedenmann.

The researchers hope that their study will also shed a light on the threat posed by climate change on coral reefs.

“Coral reefs are threatened by rising sea water temperatures and also by local impact such as pollution of the waters,” said Prof Wiedenmann.

“If we want to understand how these coral reefs respond to these forms of stress, we need to know how they are structured.

@TheCoralReefLab's Prof. J. Wiedenmann monitoring coral bleaching at the island of Wolf, Galapagos, March 2016. pic.twitter.com/hpegISXJK3

— Coral Reef Lab (@TheCoralReefLab) March 31, 2016

“One of these hypothesis is that corals escape the stress that they find in shallow waters by moving slightly deeper.

“Our work shows that the ‘deep blue sea’ may not be the welcoming sanctuary our endangered coral reefs can retreat to without consequence.

“It is of utmost importance we do our best to keep their homes in shallow water habitable.”

The research is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.