A team of scientists in the US have recreated the entire menstrual cycle into a palm-sized chip in hope that it can help solve gynaecological problems affecting millions of women around the world.

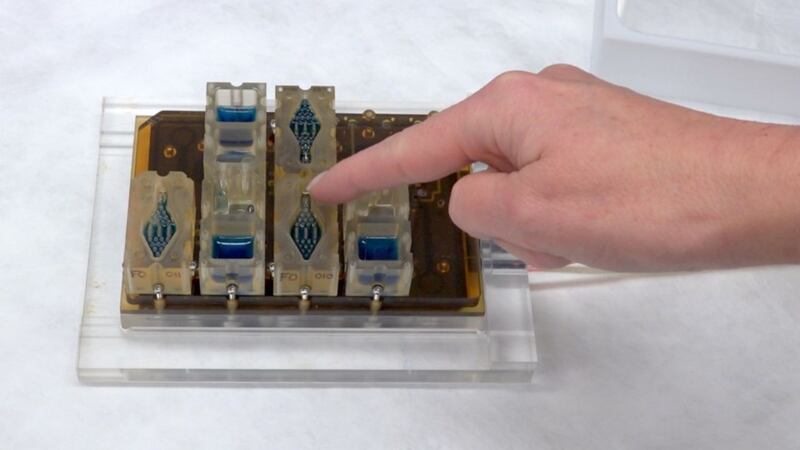

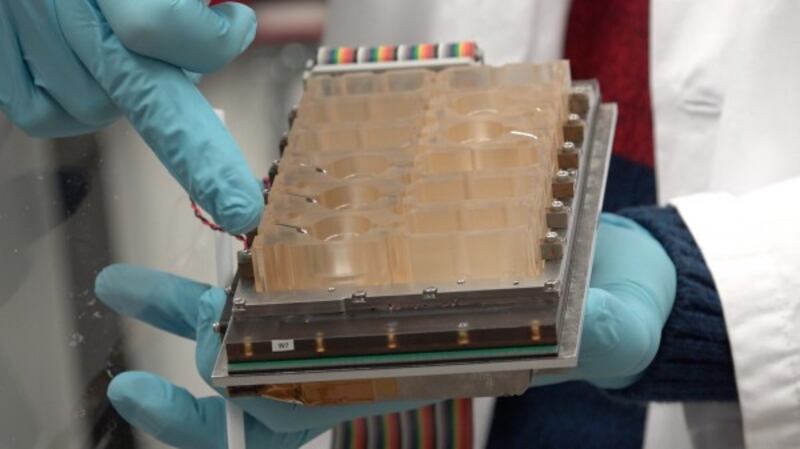

The device, called Evatar, is part organic, part tech and is made with human tissue. It contains 3D models of ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the womb, cervix and vagina, as well as the liver.

Although it doesn’t quite resemble the female reproductive system, the organ models actually communicate with one another using hormones and other secreted substances to mimic the way they work together in the human body.

Scientists decided to include a liver model because it processes and breaks down drugs and they are keen to identify effective and ineffective drugs early in the process.

Evatar is part of a larger US project aimed at producing an entire “body on a chip”.

The researchers plan to use the device to investigate conditions such as endometriosis, fibroids, reproductive organ cancers, and infertility.

Dr Teresa Woodruff, director of the Women’s Health Research Institute at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in the US, where Evatar was developed, said: “This is nothing short of a revolutionary technology.

“This will help us develop individualised treatments and see how females may metabolise drugs differently from males.”

The device also has a “circulation” consisting of artificial blood that is pumped around its different compartments.

But scientists had one important issue to tackle with the gadget.

“One of the reasons this technology has not advanced in the past is no one had solved the universal media problem,” Dr Woodruff said.

“We reasoned that organs in the body are in one medium – the blood – so we created a simple version of the blood and allowed the tissues to communicate via the medium.”

The team used ovarian tissue taken from laboratory mice because healthy ovaries are never removed from women unless in exceptional circumstances. Other tissues were human-derived.

Dr Channa Jayasena, consultant in reproductive endocrinology at Imperial College London, said: “The results are exciting and represent an important innovation. However, we must remember that the rodent and human reproductive systems have important differences.”

The research is published in the journal Nature Communications.