IRELAND'S Golden Age began with the growth of monasticism in the 6th century and flourished from then until the Viking invasions of the 8th and 9th centuries.

Throughout that period the country witnessed a remarkable flourishing of art, literature, manuscript preservation, metal-work and stone sculpture.

Trade increased, settlement patterns changed, the population expanded, the economy thrived and the lives of the people were enriched by participating in the religious rituals and festivals of their newly adopted Christian lifestyle. In many respects it was indeed a 'Golden Age'.

Culturally, Ireland was the brightest star in the Western firmament and many historians believe that were it not for the labours of the dedicated men and women of monastic Ireland the great treasures of the Graeco-Roman, Jewish and Christian scholarship would have perished in the face of pagan hostility, or indifference.

It is to these early Irish monks that we are also indebted for the diligent chronicling of ancient Irish history, legends and mythology.

Illuminated manuscripts

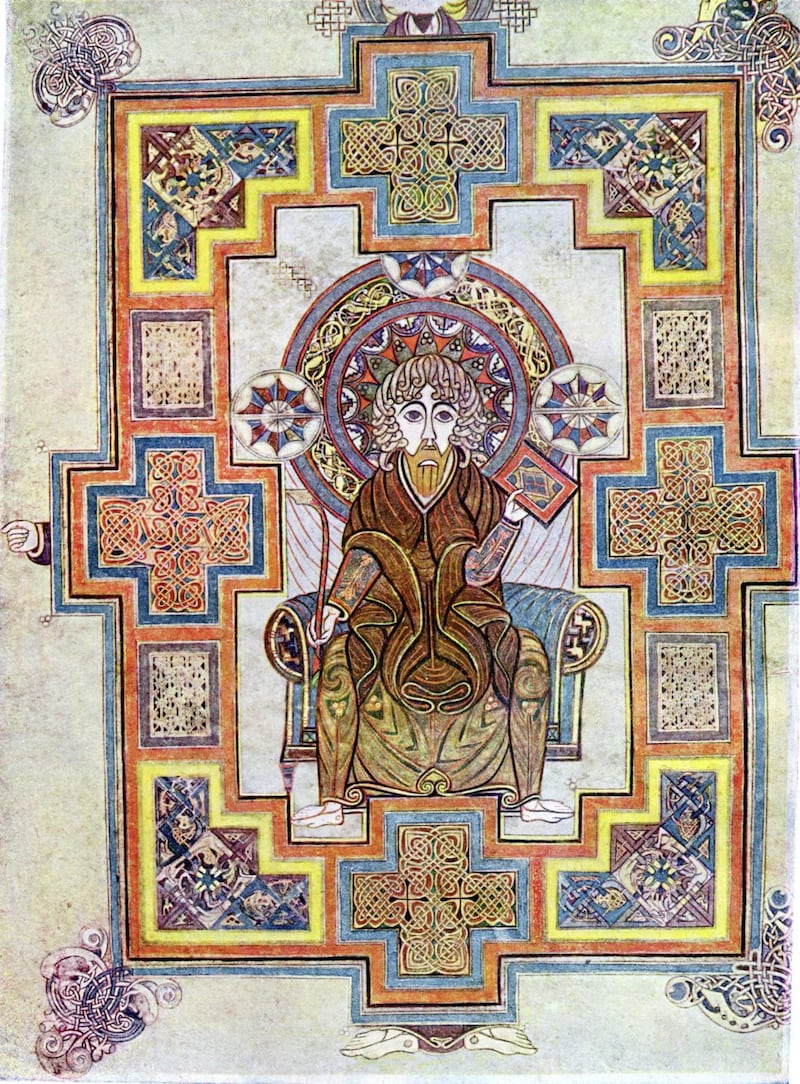

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, is the style of art produced in the post-Roman period; surviving examples are mainly illuminated manuscripts, metalwork and carvings in stone - especially stone crosses.

The most famous of these manuscripts are the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow but there are many others worthy of note, reflecting both the excellence of native scribes and the impact of external influences.

The Book of Armagh, dating from around 800 and compiled by the scribe Ferdomnach, is now in the Library of Trinity College Dublin and contains two Lives of St Patrick and the oldest - though incomplete - copy of Patrick's Confessio.

The Book of Kells represents the pinnacle of Insular illumination. In the richness of its ornamentation, the opulence of its colours, the intricacy of its knot-work and interlaced patterns and the complex decoration of its human and animal figures, it ranks as Ireland's most prized national treasure and the finest illustrated manuscript to have been produced in medieval Europe.

The Welsh priest and scholar, Giraldus Cambrensis, describing an illustrated manuscript which he saw at Kildare, and which was probably the Books of Kells, said of it: "All this is the work of angelic, not human, skill."

The Book of Kells represents the pinnacle of Insular illumination. It ranks as Ireland's most prized national treasure and the finest illustrated manuscript to have been produced in medieval Europe

The compiling of an illustrated manuscript would have taken a considerable time to accomplish and several scribes would have been involved in its completion.

Working conditions would have been far from ideal. The grandly-named 'Scriptorium' was generally nothing but a mud-walled, thatched hut without any form of heating and lit only by candle-light.

It would have been cold, draughty and uncomfortable, the work would have been eye-straining and tiring and frequently interrupted by the necessity of attending church services.

The more experienced scribes, involved in the production of more important manuscripts, carried out their work seated in front of a desk.

They wrote on parchment and vellum and for writing they used a quill made from the wing of a bird - usually a goose. The inkstand was mostly a cow horn.

Irish metalwork

There was a strong tradition of metalwork in Ireland long before the monastic period.

It is a tradition that stretches back to the Bronze Age, and artefacts from that era can be seen in the National Museum in Dublin.

The two great masterpieces of Irish monastic craftsmanship - the Tara Brooch and the Ardagh Chalice - belong to a somewhat later date in the early Christian period.

The Tara Brooch of about 700 is generally considered to be the most impressive of over 50 elaborate Irish brooches to have been discovered and is recognised as one of the most important works of early Christian Irish Insular art.

Despite its name, it was not found at Tara, but around 20 miles away on the beach near Bettystown in Co Meath.

The Ardagh Chalice is of a slightly later date and is actually part of a hoard found in 1867 in Reerasta Rath, near Ardagh, Co Limerick, during potato digging.

The great two-handled silver chalice is an elaborate construction of over 250 main components decorated with gold filigree, bronze, pewter, multi-coloured enamel and brass fittings; other semi-precious materials used include glass, amber malachite and rock crystal.

The chalice was originally used for dispensing Eucharistic wine during the celebration of Mass; today it ranks as the finest work of metal produced in Ireland and a supreme example of Insular art, indeed of Celtic art in general.

The much-prized Sam Maguire Cup is a replica of the Ardagh Chalice.

Other artefacts dating from this early Christian Ireland art period include the Derrynaflan Chalice, the Moylough Belt Shrine and the somewhat later processional cross, the Cross of Cong.

Irish high crosses

Together with illuminated manuscripts and metalwork, Irish high crosses represent the third major contribution to the history of Irish art in the early Christian period.

Most of them date from the 7th to the 12th centuries and fortunately many have survived the ravages of time.

They are among the most remarkable of all monuments and remain virtually the only elaborate free-standing monuments of the early Middle Ages in all of Western Europe.

Their distinctive shape has become identified with Ireland itself and is frequently replicated in Irish jewellery, one example being the much coveted medal awarded to the winners of the All Ireland Football Championship.

The high crosses are among the most remarkable of all monuments and remain virtually the only elaborate free-standing monuments of the early Middle Ages in all of Western Europe

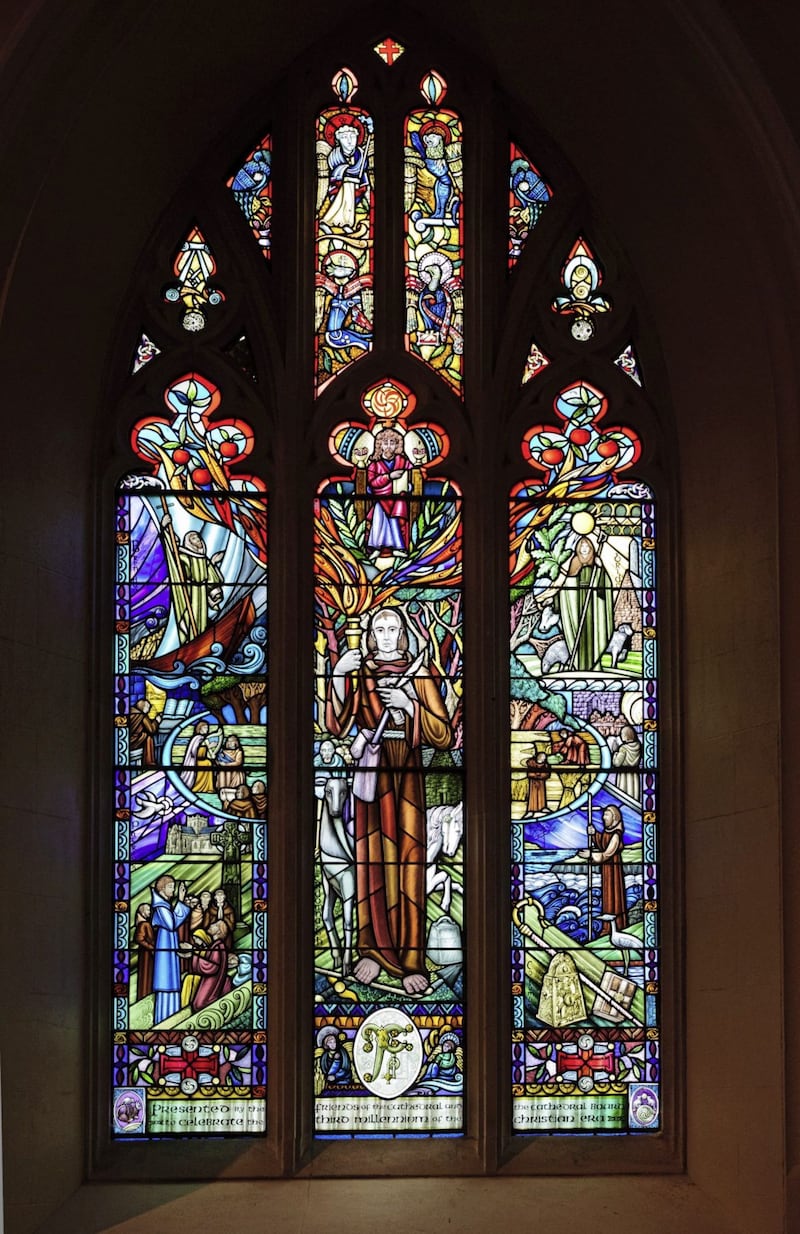

The great scriptural crosses were used to teach the lessons of the bible, in much the same way as stained glass windows in the medieval period became 'the poor man's bible'.

In appearance most high crosses resembled a big, square pillar of stone culminating at the top in the form of a cross; the component parts were a pyramidal base, a shaft, a ring of stone, both symbolic and functional, connecting the arms to the upright shaft, creating the characteristic outline of the cross, and a capstone which bore some resemblance to the small early Irish churches of the period.

The debt to pagan Celtic tradition and the Insular art work of the illuminated manuscripts is evident in the abstract design on some of the earliest high crosses, but this gradually gave way to figurative representation of Biblical scenes or sometimes a combination of the two.

In the grandeur of their conception and the excellence of their construction, the high crosses of Ireland remain as unique documents in the history of sculpture and striking memorials to the talented men who created them.

Frank Rogers is the author of The Story of Ireland in Stained Glass and The History of the Convent Chapel, Enniskillen.