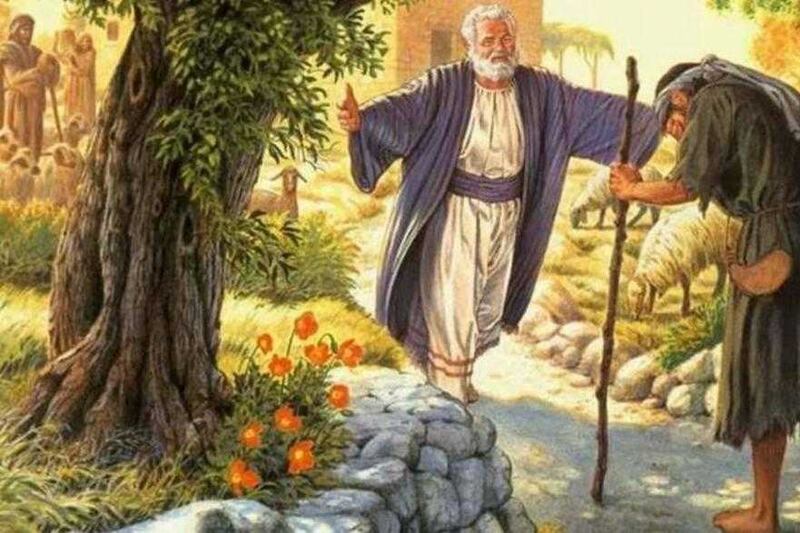

ONE of the best-known and best-loved stories in the gospels is the parable of the Prodigal Son.

With its promise of forgiveness and reconciliation for the repentant sinner, it has no doubt been a source of consolation to many down through the centuries.

Yet to interpret the parable as a domestic drama with a happy ending, hinting at God's great patience with wayward human beings, doesn't seem to exhaust the story's meaning.

Above all, it doesn't account for the fact that, while the parable of the Prodigal Son has become almost a byword for 'happy endings', the story doesn't actually have an entirely happy, cloudless ending at all.

On the contrary, it has a quite problematic, even a rather unpleasant, ending.

The Prodigal Son may indeed have returned home, to his father's great joy and relief, but the sullen, resentful attitude of the older brother spoils to some extent, or at least casts a shadow over, the happiness that the Prodigal's return had brought to his father.

The older brother refuses to let himself be influenced or infected by his father's joy.

One problem, in short, seems solved, only to give rise to a new and perhaps even more intractable one.

If we take this ending seriously, we might want to argue that the parable is trying to teach us something that we usually find so difficult to accept fully.

This is quite simply that there appears to be no such thing as perfect happiness on earth, even though, like the Prodigal Son, we seem to have an ingrained, even at times a reckless desire to seek the happiness that we are told our first parents enjoyed in paradise, but which they eventually lost through the exercise of their freedom.

Now, if the bad news is the banal truth that the quest for happiness can apparently reach no definitive or satisfactory goal within the limits of human history, the good news is that there is an equally constant, and more benign, more promising factor also to be found within human history.

The fact that all human plans for perfection and happiness seem eventually to unravel in the course of history is not necessarily the end of the world

This is embodied in the parable by the father who, as father, is the constantly unchanging and undeniable source of his children's lives and is occasionally glimpsed as the benevolent, non-intrusive spirit interested in their happiness.

These two forces we cannot but recognise in the fabric of our own lives: on the one hand, our almost predictable, and frequently destructive and self-assertive, search for happiness and, on the other, our final dependence on the ultimate source of life, which Christianity believes to be fundamentally good, and creative rather than destructive.

Where the specifically good news of the gospel can illuminate and redeem human life is in the hope it holds out about the ultimate coinciding of God's creative action with the human drive for happiness.

The fact that all human plans for perfection and happiness seem eventually to unravel in the course of history is not necessarily the end of the world.

At least it doesn't necessarily signify the definitive failure of God's redemptive will for us.

The God who maintains contact with us by sustaining our existence in this world can also be relied on, in other words, to bring to fulfilment the work he began in us.

But since that fulfilment involves, we believe, ultimate union with God, the source of our life, it can presumably only be realised where this life has its origin - in other words, beyond the world of normal, everyday experience.

Small wonder that the Prodigal Son instinctively sought happiness beyond and outside his normal world.

What the parable of the Prodigal Son suggests, however, is that the idea of finding happiness beyond our world in any straightforward sense is an illusion.

But what the parable also suggests, is that the idea itself of finding happiness is not an illusion. It is a reality, guaranteed by God.

The parable of the Prodigal Son is perhaps not fundamentally, then, a story about repentance and reconciliation.

It is maybe more a story about the human hope for happiness and, above all, about where alone this hope can be fulfilled.

It cannot be fulfilled by abandoning or denying the basic limitations of the human condition.

Rather, only by embracing and affirming those limitations can we be embraced by what creates and sustains and transcends them.

Martin Henry, former lecturer in theology at St Patrick's College, Maynooth, is a priest of the diocese of Down and Connor