SAT behind the his little Olivetti typewriter, tapping at its keys as yet another sheet of paper circled the roller, Fr Raymond Murray could have been any other priest preparing his homily or parish bulletin.

Yet Fr Murray was emphatically not 'any other priest'.

Throughout the Troubles he was at least as likely to be producing another pamphlet, article or book detailing the excesses of the state and human rights violations as he was anything more directly related to the worship in Armagh's cathedral parish.

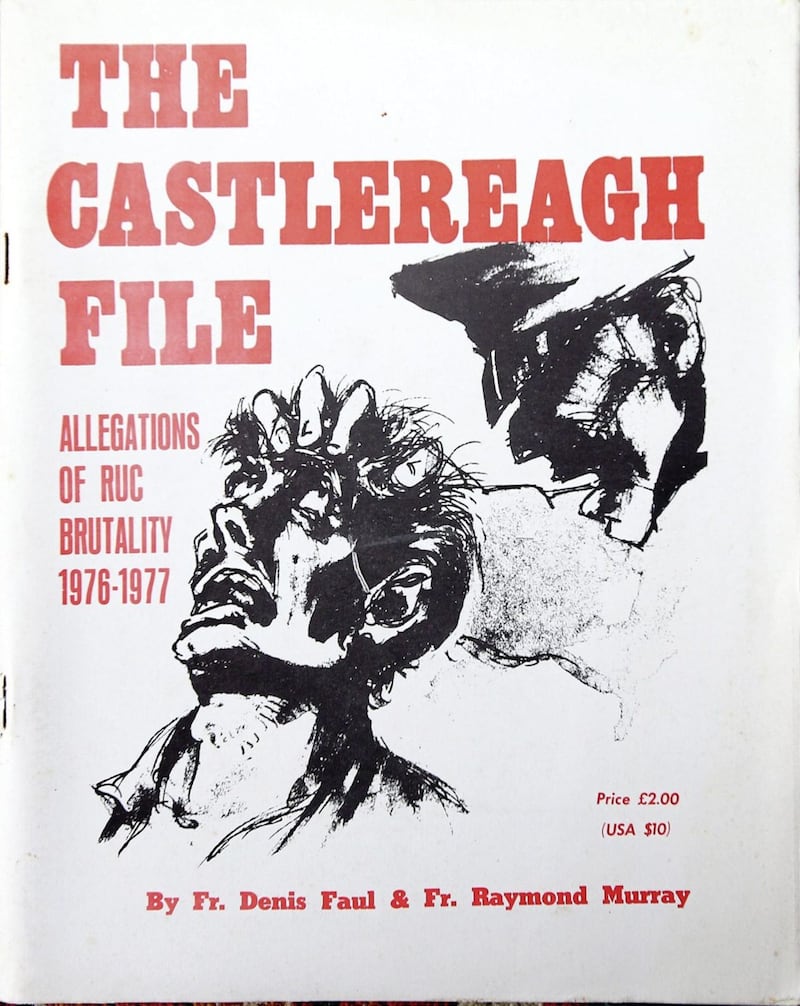

Over the years he has authored dozens of such publications, many of them with his colleague the late Fr Denis Faul.

This work has brought him a certain prominence or, some might say, notoriety; highlighting the mistreatment of republican prisoners by the UDR, RUC and British army, arguing the cases of the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six, campaigning for the 'Hooded Men' and detailing the activities of the SAS has never been wholly easy.

His name might be most widely known for these contributions and others to human rights, but along with his vocation as a priest there is a third, sturdy leg to the stool upon which Raymond Murray's public life rests: his devotion and dedication to the study of history.

You do not have to spend long with Monsignor Murray - Cardinal Cahal Daly appointed him and Fr Faul honorary prelates on the same day in 1995 - to appreciate that the vigour with which he set about the task of highlighting human rights violations was the result of a determination that an accurate, contemporaneous record should be kept.

"When you read 19th century Irish history, so many of the stories were dependent on British papers and sources and were one-sided," he says.

"That is why I wanted to record what was happening. I asked myself, 'In 50 years' time who will people believe? This pamphlet? Or another source?'"

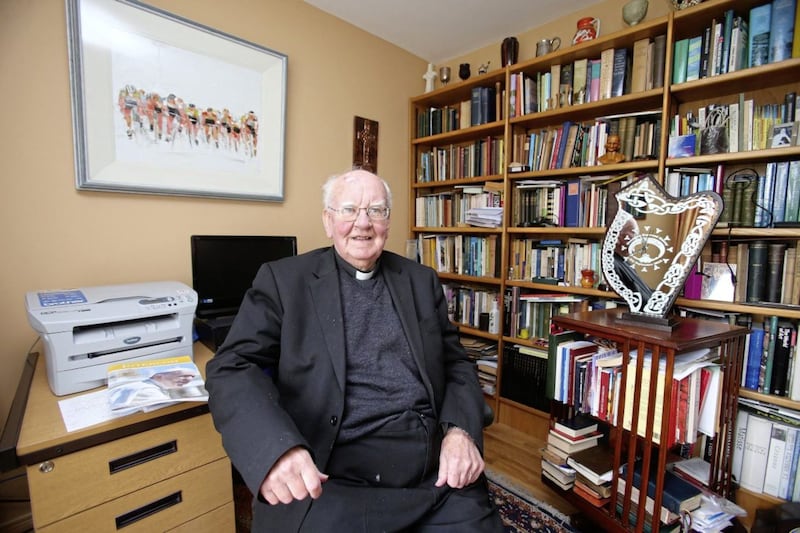

Msgr Murray celebrated his 80th birthday last month. It is an appropriate landmark from which to reflect on his own history. We meet in his home in Armagh.

There are, of course, copies of his many pamphlets and books, ranging from slender volumes of statements taken from interned prisoners in the early 1970s to his 500-plus-page tome The SAS in Ireland.

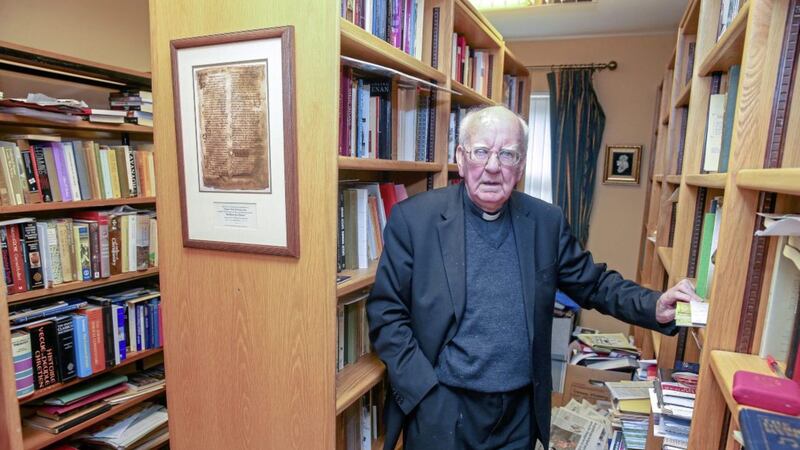

But these are enormously outnumbered by the hundreds of volumes dedicated to history and theology.

Bulging book cases don't simply line the walls; in one room in particular, they also stand sentinel in the middle of the floor, creating the impression of a particularly well stocked university library.

He has given "hundreds and hundreds away" he says, almost apologetically.

Msgr Murray had his own library in a room in the Sacred Heart Convent in the city, but those books have now been moved to the nearby Ó Fiaich Library.

He was instrumental in setting up the library, established in memory of his great friend - and fellow historian - Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich.

The Irish language and poetry are other interests, though it is rather underselling his achievements to describe them as such; his poetry collection Lampaí Dearga won the Oireachtas Prize for poetry in 2005, for example.

One feels that Msgr Murray might have been perfectly content to have pursued his ministry and historical studies under more conventional circumstances.

But, as with so many others, the Troubles changed all that.

"The real start for me was internment," he says.

"I was on holiday with my friend Fr Paddy Campbell in Spain and we were on the train. The man sitting opposite me was holding up a newspaper, and I saw the headline, 'Guerra Civil en El Ulster' - 'Civil war in Ulster' - and we were shocked."

Arriving back in Armagh shortly after August 9 1971, he found the city deserted at night-time. "There was a great stillness," he remembers.

Two of those from Armagh who were interned, Patrick McNally and Brian Turley, later became among the 'Hooded Men' who were singled out for sensory deprivation torture and with whose cause Msgr Murray is synonymous.

In the months that followed, Fr Murray, then a curate in St Patrick's parish in Armagh, was routinely contacted by the families of those in the area who had been arrested.

A phone call from Fr Faul in December 1971 proved a watershed moment.

"He told me that the overflow from Crumlin Road - about 40 men - was being sent to Armagh," says a reflective Msgr Murray.

"I went to see them, and that's what really changed my life."

The men had evidently been very badly beaten - "I had never seen such bruising in all my life... a cattle prod had been used to give them electric shocks" - and the sight prompted Fr Murray to start his practice of taking their statements.

"I got an independent doctor to examine them, so I also had medical reports," he says.

He passed his material to Cardinal William Conway, the Archbishop of Armagh at the time, who got in touch with the Northern Ireland Office, albeit to no effect.

"He later sent a telegram to the Australian bishops, a ploy to get publicity about the ill treatment," says Fr Murray.

"We didn't have the same methods of copying in those days, but I typed up everything on my little Olivetti typewriter and got the local slipper factory to copy it for me.

"I had 35 copies made, and headed down to Dublin to see the editors of the newspapers - I sent some to the Irish News, too - but they weren't that keen.

"They didn't want to get involved. It was hard to get the media interested in those days.

"It took the Sunday Times and its reporter John Whale to get involved before the Irish papers got behind it."

As the Troubles escalated, Fr Murray found himself becoming, as he puts it, "roped in more and more".

"I got friendly with the Association for Legal Justice, worked with friends of people who had had people belonging to them jailed, and set up Relatives for Justice - it was all to put on record what was happening," he says.

When you read 19th century Irish history, so many of the stories were dependent on British papers and sources and were one-sided. That is why I wanted to record what was happening

His parishioners were "all for me" at this increasingly demanding work.

"They understood the situation," as he pithily sums up their attitude.

However, I wonder whether the Church hierarchy was as understanding.

"I was never reprimanded. Cardinal Conway kept his own note of all the killings and saw it was important work," he says.

"The danger was so great that lawyers weren't getting involved. They were scared of getting shot."

In that context, it was important for figures like the clergy to play their part.

Writing in 2015, he said: "Fr Denis Faul and I condemned republican murders but concentrated on state violence since out of fear there were less people drawn to that.

"We were lone figures in many ways since other leaders, facing often the hostility of the British government and elements of the British press, had not the courage to do so."

His own life was at times threatened - including reams of anonymous letters and a bullet in the post - but he doesn't remember being scared himself.

"When you're young you have a strange mentality... The police came to me on a number of occasions to tell me my life was in danger," he says.

"They would say things like, 'We would like to stay in the grounds of your house,' and I would have no objections."

He remembers one occasion when he was invited to address a historical society in Markethill who were keen to hear more about his research on a Church of Ireland cleric.

"The police told me that the UVF were threatening to shoot me. 'If you like, we will go there,' they said," he says.

"I thought it best to cancel it and spoke to the historical society, which was a mixed group.

"They wanted to hold it in Armagh instead - they weren't going to be beaten either."

In the atmosphere of the time, loyalist paramilitaries may have felt emboldened to threaten a priest because of a perception that because Msgr Murray's work brought him close to republican paramilitaries, he must also have affirmed them.

"It wasn't that we were supporting them or sympathetic with their methods," he insists.

"There were murders going on - by the state or through collusion - but they weren't getting justice."

He and Fr Faul condemned murders by the IRA and INLA. In 1984 they wrote: "What do the Catholics want? They don't want the Provisional IRA and still less the INLA.

"They want to be treated in such a way that their young people could be prevented from joining these ruthless organisations..."

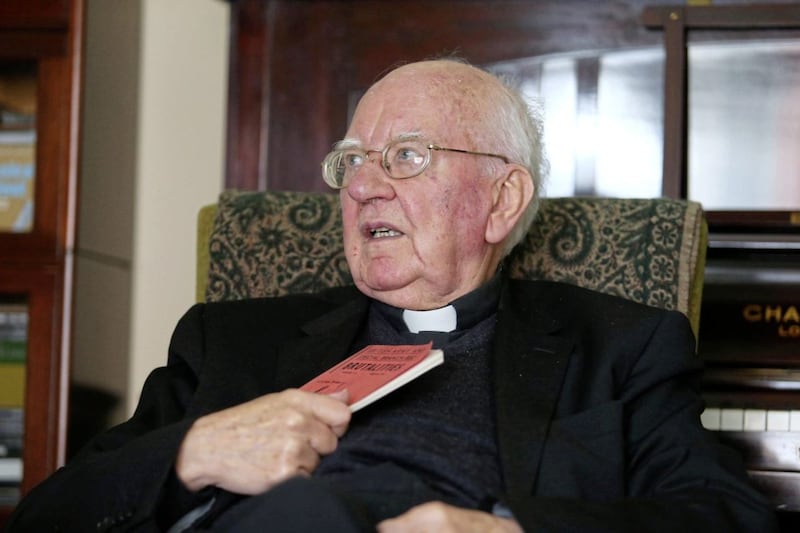

Msgr Murray continued with the painstaking task of "putting things on record" throughout the Troubles.

Nonetheless, "the brutalities continued".

Even so, Msgr Murray cannot countenance that such efforts were pointless: "I was doing it because it was going on the record. Who are people going to believe in the future?"

Again, the commitment to history.

As a student at Maynooth and Queen's University, Belfast, the young Raymond Murray fed hungrily on Seanchas Ard Mhaca, the learned journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society.

I'm 80 years of age, and I've been through the mill over the years. I'll personally need to be turning more to religion and spirituality for myself before going up above, skywards

The society was founded in 1953 and Tomás Ó Fiaich - Fr Murray's history professor at Maynooth - was the journal's first editor.

Msgr Murray was destined to become heavily involved in Seanchas Ard Mhaca.

"Tomás was appointed to head of the Commission for the Irish language, so with his own work and all he had to do, the journal stopped for five or six years," he recalls.

Msgr Murray was involved in persuading Cardinal Ó Fiaich to resume the reins at Seanchas Ard Mhaca, but when he was appointed Archbishop of Armagh in 1977 "he didn't have time to do it".

"My friend Fr Paddy Campbell - a good historian and great scholar - then edited the journal," he says, before adding - with modest understatement that belies a significant contribution: "Then I took it on for 27 years until recently..."

With Cardinal Cahal Daly, Msgr Murray was an executor of Cardinal Ó Fiaich's will when he died in 1990.

He had left his books and historical papers to the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society - a generous bestowal, for sure, but it did raise the practical question of what to do with such a vast archive.

"The committee debated what we could do, but we were not sure where we could find a place for all of the books," Msgr Murray says.

After exploring a few options, they resolved to build a library - not only for the Ó Fiaich collection but also for "the things Tomás was interested in - the Irish language and the Celtic languages, Irish history, local history and the Irish abroad".

Msgr Murray becomes animated as he talks about the library - "Cardinal Daly was very kind and gave us part of his garden..." - and it is clear that he regards it as a high point in an eventful life.

He may be expert in Armagh and aspects of Irish history but Msgr Murray's interventions in human rights have also seen him travel the world.

"Because the UK was concerned about its good name internationally, we decided we needed to go and spread the word abroad as to what was going on here in the violation of human rights," he says.

"Fr Faul and I spoke at different events in England, Scotland, were invited to the United States and spoke to officials in the United Nations.

"I went to the UN in Geneva to talk about plastic bullets."

He mentions various figures - Sister Sarah Clarke, Fr Sean McManus, Rita Mullan and others - with whom he worked over the years.

Germany, Italy, Poland, France, Colombia are a few of the other countries he visited.

"They always listened very sympathetically to you. The whole point was to embarrass the British government by spreading the word abroad."

The Catholic Church today, perhaps particularly in Ireland, finds itself in a very different dispensation than that for which the young Fr Murray was ordained in 1962, the same year that the Second Vatican Council opened.

Through sheer workload, it seems doubtful that a priest today would have the time to pursue the same work that Msgr Murray was able to embrace with such energy and commitment from the 1970s.

The breadth of that work would be noteworthy at any time, however.

In the view of Fr John Bradley, president of the Society of Seanchas Ard Mhaca, Msgr Murray "should rightly be acknowledged as one of the outstanding Irish priests of the modern age" because of his "lifelong commitment to the Church in every respect, his immense output as an historian, his internationally acknowledged commitment to human rights and his literary and cultural achievements".

When he was ordained, the Archdiocese of Armagh had a surplus of new priests to the extent that it was able to loan 11 elsewhere.

Fr Murray was one of four sent to Belfast, where he was dispatched to the burgeoning Holy Trinity parish in the west of the city.

He would encounter some of those same parishioners many years later, during the IRA Hunger Strike in 1981.

"I remember being invited by the Redemptorists to give a talk at Clonard," he recalls.

"Afterwards a woman came up to me and reminded me that I had buried her daughter.

"She then said that [hunger striker] Joe McDonnell had died, and that she was his mother."

Conversation with Msgr Murray is full of such asides and reminisces.

As for the health of the Catholic Church in 2018, he is content to take the historian's long view.

"The Church has always had problems. It's very saddening, but there is a lot of change and problems aren't new," he says.

Referring to Matthew 28:20, he adds: "Jesus said, 'I will be with you until the end of time.' The Church has always faced problems but it has always come through."

Msgr Murray has faced some problems of his own in recent years, including bouts of ill health.

Given his involvement in what now tends to be euphemistically described as the 'legacy issues' of the Troubles, I ask him how he thinks they might be resolved.

He is, however, reluctant to say too much. Instead, his focus is on the brightness of a heavenly future rather than the darkness of the past.

"I'm 80 years of age, and I've been through the mill over the years," he says.

"I'll personally need to be turning more to religion and spirituality for myself before going up above, skywards."

That includes finally getting round to some more reading; German historians and theologians are on the agenda when we talk, with "a Ratzinger" - a reference to Pope Benedict XVI - on the go.

"I have plenty of books to keep me busy," he says, gesturing to his shelves, "before my next journey."