GIVEN his lifelong friendships with Christians of other denominations and the particular circumstances of Northern Ireland which lent particular urgency to the task, Cahal Daly was deeply convinced of the necessity of ecumenical dialogue.

"The growth of unity within the Church must motivate us also to pray and work for unity between the Churches," he said.

"Ecumenism is not an optional extra for priests or for laity. It is a command of the Lord and a response to his own prayer.

"The ministry of reconciliation which bishops and priests have received from the Lord through the Apostles is incomplete unless we are working also for reconciliation between divided Christians."

From the outset Cahal Daly was involved with the Ballymascanlon Inter-Church meetings and succeeded in establishing excellent relations with leaders of the other Churches.

He was well aware of the difficulties, ranging from hostility, suspicion or indifference to foolish enthusiasm and naïve optimism, but this did not deter him from continuing to work loyally and lovingly for ecumenism, in fidelity to the directives of the Second Vatican Council.

Taking his cue from Paul VI, he insisted on the primacy of spiritual ecumenism, by which he meant a change of heart and holiness of life, rooted in prayer.

All bitterness and bigotry should be purged, while attitudes of mutual understanding, mutual respect and the presumption of reciprocal good faith, sincerity and integrity should be cultivated. Charity, Daly believed, is the soul of dialogue.

"We must be eager to learn from one another, to receive from one another, rather than to discredit or triumph over one another," he said.

"We must, once and for all, renounce any idea that one of us could succeed through the other's failure, could prosper in the other's adversity, or rejoice in the other's loss.

"Catholics must learn to rejoice in the Christian faith and fervour and witness of Protestants, and Protestants must learn to rejoice in those of Catholics."

During Cahal Daly's episcopate, much progress was made in ecumenical dialogue in Ireland, although he was also aware of the danger that it could be limited to small groups of specialists, with little impact on the lives of the individual faithful.

He encouraged greater knowledge and study of the documents produced by various ecumenical discussions and recommended that the principles of ecumenism and some initiation into its practice should be regarded as indispensable elements in all religious education programmes, so that the fruits of ecumenical dialogue could percolate to all levels of the Church, thus facilitating mutual understanding and reconciliation between divided Christians.

Although he was a staunch defender of Catholic schools and attracted criticism in certain quarters for his unwillingness to promote integrated education, Daly insisted on the need to promote the ecumenical spirit in the formation of Catholic pupils at all levels.

Cahal Daly's unwavering commitment to ecumenism was deeply rooted in his love for Christ and his desire to have "the same mind as was in Christ Jesus".

Although the pursuit of Christian unity through dialogue is a distinct undertaking from the quest for peace, ecumenical dialogue assumed particular urgency during the years of the Northern Ireland conflict.

The leaders of all the major Christian denominations made strenuous efforts to bring an end to the violence which caused untold suffering to people on all sides of the religious and political divide.

As Bishop of Down and Connor and later as Archbishop of Armagh, Cahal Daly made an important contribution to the peace process.

Apart from his strong and unambiguous condemnation of violence, no matter where it originated, and his encouragement to those involved to engage in dialogue, he made valiant efforts to convince the civil authorities to deal with the excesses of the security forces, guarantee humane conditions for prisoners and tackle the social injustices and deprivation which fuelled resentment and provided a breeding ground for paramilitary involvement.

One of Cahal Daly's most important and courageous contributions to the peace process was his insistence on the need to recognise and respect the two traditions, unionist and nationalist, in Northern Ireland and their respective civil and political rights and aspirations.

Without this, he was convinced, there could no political solution and no peace in the north.

In the volume The Price of Peace, published in 1991, he explained it thus.

"Northern Ireland's problem is that of how to find ways of sharing two traditions, not ways of suppressing one or other tradition, or of subordinating one to the other," he wrote.

"It is a problem of giving political expression to two equally valid loyalties, which each have an equally valid historic and moral right to be, and to be constitutionally recognised as being, an integral part of Northern Ireland.

"Recognition of two Ulster loyalties, two Ulster identities, is an indispensable precondition of any solution to the complex problems of Northern Ireland."

Despite the seemingly insurmountable obstacles to finding an acceptable political solution, Cahal Daly never became despondent, convinced as he was that Christianity would have the last word, and that word is love.

"To believe in God's love towards ourselves is to believe also in God's love towards others, even when they are different from ourselves," he said.

"It is to believe in the rights of others to be different from ourselves. The wish to extinguish differences is secretly a wish to eliminate those who dare to differ.

"Reconciliation across accepted differences is a direct consequence of believing in 'God's love towards ourselves'."

As the peace process gathered momentum during the 1990s, Cahal Daly redoubled his efforts to persuade all involved to grasp the opportunity, abandon violence and embrace the cause of love, justice, peace and reconciliation.

He was convinced that in the long term, "the constitutional position of Northern Ireland [would] be determined by the evolution of the political process between its two communities and by democratic dialogue between its two traditions".

No solution could be imposed from outside; only a change of heart on all sides could bring about an acceptable political solution.

Notwithstanding some setbacks on the way, the courage and commitment of Northern Irish political leaders on all sides, assisted and encouraged by the American, British and Irish governments, eventually led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

The principle of constitutional recognition of the legitimate civil and political rights and aspirations of the two traditions in Northern Ireland, on which Cardinal Daly had insisted, would prove fundamental to the power-sharing institutions which the Agreement established.

By then in retirement, Cardinal Daly warmly welcomed the Good Friday Agreement and prayed for its success, mindful as he was of the need for continued restraint and responsibility on the part of all concerned.

No doubt, he would remind us today of the need to continue to engage in dialogue and go the extra mile in order to overcome the difficulties that crop up from time to time. As he wrote some years earlier, "there is no alternative to dialogue".

Cahal Daly's approach to the question of relations between Church and State in today's Ireland is also influenced by the same commitment.

He was well aware of the frequent calls for 'separation of Church and State' and of the misunderstandings that arise in connection with this notion.

In fact, there is no single universal model of separation, as the political systems of various countries clearly demonstrate.

Cahal Daly certainly believed that Church and State should be seen as distinct and autonomous in their respective realms.

As he stated at the New Ireland Forum in 1984, he was not favourable to the concept of a confessional State, since such an alliance between Church and State would be harmful to both.

At the same time, he did not believe that the Church should remain silent on all matters of legislation and social concern, as though she had no right to take public positions and issue moral judgments on social and economic questions.

To impose silence in these matters would be a denial of the fundamental democratic principle of religious liberty, which requires that the Churches have full freedom to proclaim the Gospel.

There obviously can be laws which are in conflict with the moral teachings of the Gospel and the Church must have the freedom to point this out.

While the Church does not expect civil legislation to conform to Church teaching, it does have "the right and duty to form and to inform the consciences of those citizens who are Catholics about the moral implications and the moral consequences of proposed laws or constitutional changes, leaving it to their duly informed consciences how to act and how to vote".

Separation of Church and State "cannot entail separation of either legislator or voter from his or her conscience".

In other words, while recognising that there are other legitimate considerations to be taken into account in drafting legislation, the Church claims the right to contribute to the debates about the formulation of laws and, more generally, about issues affecting the lives of citizens.

The Church's contributions are not matters of faith only; "they are also open to reasoned conviction on the part of any citizen, and they are often accepted by people of different traditions on grounds of reason, rather than on grounds of faith".

Obviously, if something is good and true in itself, it does not cease to be so because the Catholic Church teaches it.

Naturally, the Church seeks to engage in public debates and put forward her position in a spirit of dialogue and respect for the institutions of the State and the democratic right of citizens to express themselves.

Tensions, disagreements and even divisions can arise, but this is part of any normal healthy democratic process.

Mature relations between Church and State are characterised neither by subservience nor by opposition but by what the Second Vatican Council calls "wholesome, mutual cooperation" with due respect for the legitimate autonomy of both sides.

Although Cardinal Cahal Daly died before the election of Pope Francis, there are some interesting points of contact between them.

The recent Jubilee of Mercy served, among other things, to raise awareness about the plight of prisoners; indeed visiting prisoners is one of the seven corporal works of mercy.

Like Pope Francis, Cardinal Daly devoted considerable attention to the pastoral care, humane treatment and rehabilitation of prisoners, insisting on the need for mercy and clemency in their regard.

A further similarity lies in the Cardinal's emphasis on dialogue, which shows him to have been a promoter of what the Holy Father calls a "culture of encounter".

The Pope uses this expression to emphasise the need to step out of our own comfort zones, to be fearless in looking beyond our own needs and aspirations to those of others and to go out and meet them. This is how 'encounter' takes place.

Like dialogue, the culture of encounter is not a mere technique for ensuring better human relations but is theologically rooted in our prior encounter in faith with the love of Jesus.

Jesus takes the initiative in encountering us and prompts us to do as he did: encounter others.

Encounter overcomes isolation and exclusion; it implies respect for the dignity of others and seeks to establish interpersonal relations with them based on mutual respect, love and reciprocity.

It implies risk, because in reaching out to others we expose ourselves and become somewhat vulnerable.

This is because authentic encounter requires a response: we reach out to others in the hope that they will not reject our overtures but will grasp the opportunity to engage with us.

We could make mistakes but this should not deter us. As Pope Francis once said: "What happens if we step outside ourselves? The same as can happen to anyone who comes out of the house and onto the street: an accident.

"But I tell you, I far prefer a Church that has had a few accidents to a Church that has fallen sick from being closed."

Building a culture of dialogue naturally involves risks and possibilities, similar to those mentioned by Pope Francis when he speaks of a Church which is willing to step outside herself.

Dialogue is obviously challenging and difficult. It requires much patience and perseverance. It requires us to face up to those forces of prejudice and entrenched positions within our own communities and indeed in our own hearts which hinder the possibility of accepting others as they are and listening to their legitimate concerns and aspirations.

Despite the possibility of failure, we must never give up trying nor should we surrender to pessimism and despair.

The only alternative is the imposition of the logic of power, whose tragic consequences all over the world are plain for all to see.

Hence, there is a moral imperative to pursue dialogue. We must do so in season and out of season, honestly and transparently, with a listening ear and an open heart.

On the centenary of his birth, Cardinal Cahal Daly's teaching on dialogue has lost nothing of its relevance and urgency.

Let us learn from his example and act always in accordance with the spirit of dialogue which he sought to inculcate and promote.

Above all, no matter what it may cost, let us be courageous and never hesitate to go the extra mile.

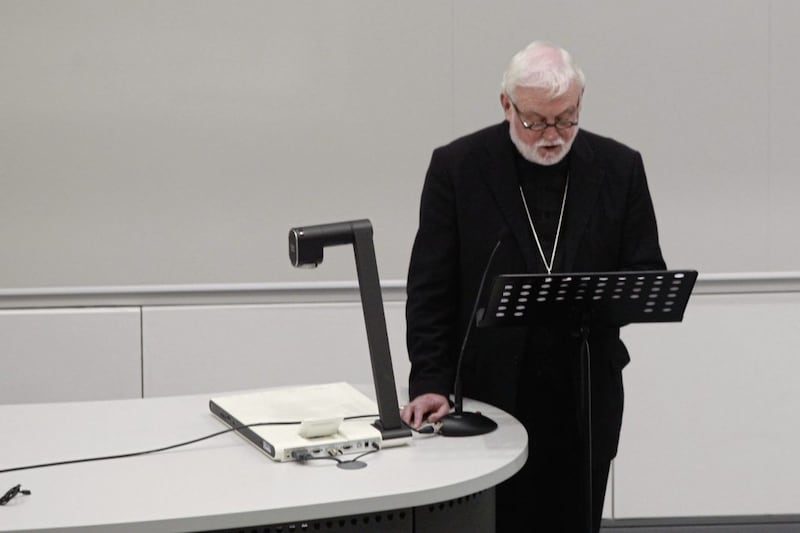

:: Abridged from 'Go the Extra Mile - Cahal B. Daly: Reflections on the Practice of Dialogue', a memorial lecture to mark the centenary of the birth of Cardinal Cahal Daly. The lecture was given in Queen's University Belfast last Friday by Archbishop Paul Gallagher.

:: Archbishop Paul Gallagher, a priest of the Liverpool Archdiocese, has spent over 30 years in the Vatican's diplomatic service, including as Apostolic Nuncio to Burundi, Guatemala and Australia. In 2014, Pope Francis appointed him Secretary for Relations with States in the Secretariat of State of the Holy See.

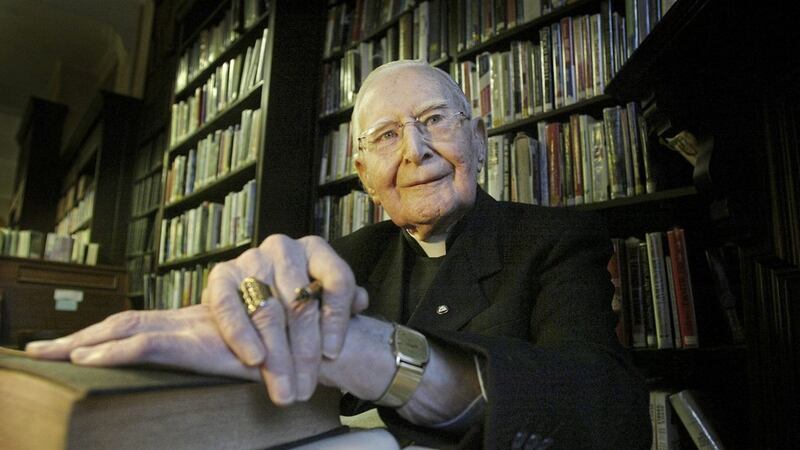

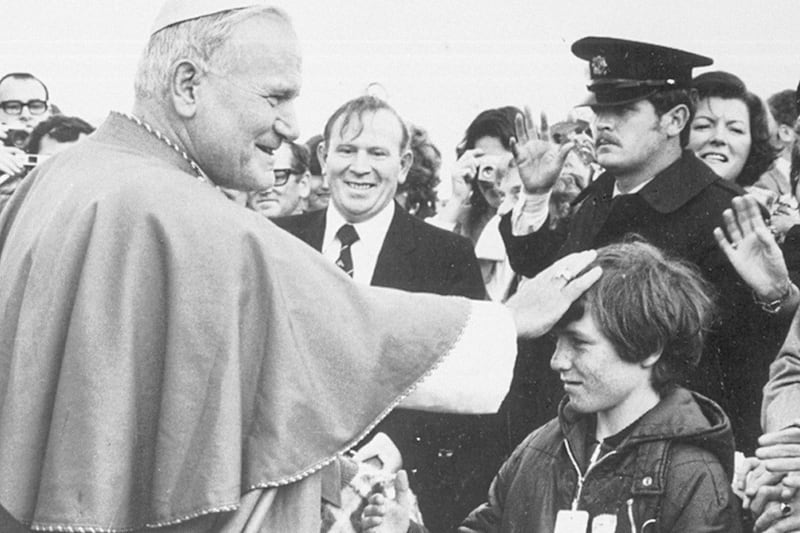

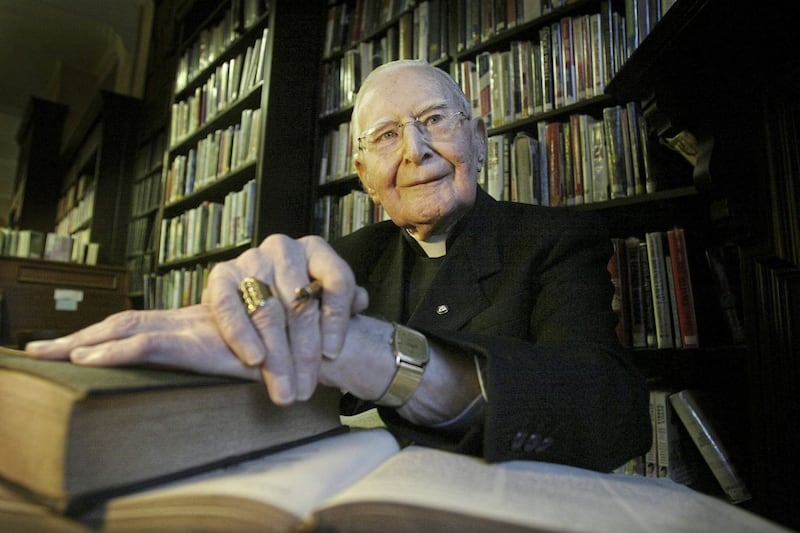

:: Cahal Daly was born in Loughguile, Co Antrim on October 1 1917. He was ordained in 1941 and a distinguished academic career included a long association with Queen's University Belfast, where he lectured in Scholastic Philosophy. He was a theological adviser to Bishop William Philbin and Cardinal William Conway at the Second Vatican Council. In 1967 he was appointed as Bishop of Ardagh and Clonmacnois; in 1982 he was transferred to his home diocese of Down and Connor and in 1990, at the age of 73, he became Archbishop of Armagh. Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal in 1991. Cardinal Daly retired in 1996 and died on December 31 2009, aged 92.