BACK in the 1980s, when I worked as chaplain in UCD, I took part in some of the debates hosted by LawSoc, the university's law society, and the L&H, the literary and historical society.

One night, after a debate on the causes of political change, I went for a drink with a few of the other participants, two of whom were politicians who would later be government ministers.

One of them, said to me: "You know Father, Christianity and political liberalism will never see eye-to-eye.

"We both identify the problems; we are both interested in finding solutions, but while we focus primarily on the ends to be achieved, you people also worry about the appropriateness of the means."

And it is true; we concern ourselves with the means because they are part of what makes any course of action moral or immoral.

Pope Francis, in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, argues that we would not be "well served by a pure sociological analysis which would aim to embrace all of reality by employing an allegedly neutral and clinical method".

"What I would like to propose", he says, "is something much more in the line of an evangelical discernment".

"It is the approach of a missionary disciple, an approach 'nourished by the light and strength of the Holy Spirit'," he says.

"We need to distinguish clearly what might be a fruit of the kingdom from what runs counter to God's plan.

"This involves not only recognising and discerning spirits, but also - and this is decisive - choosing movements of the spirit of good and rejecting those of the spirit of evil."

The unavoidable question, of course, is the question first asked by the teacher of the law: "Master, which is the greatest of the commandments?" Jesus replied "you shall love the Lord your God with your whole heart and you shall love your neighbour as yourself".

Like a good lawyer, the man immediately asked: "Who is my neighbour?" If you wanted to be cynical you might say he was looking for some way to limit his exposure.

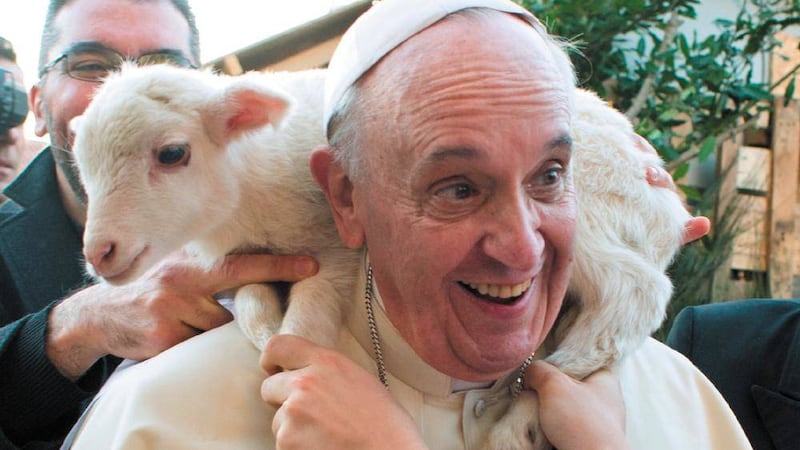

It is not altogether surprising that people find the various profiles of Pope Francis challenging.

Philosophers since the time of Plato have struggled to come to terms with the unity and integrity of the human person.

Plato believed that the soul was immortal, but this belief went hand-in-hand with the idea that the human body was not really part of the person.

Aristotle believed so strongly in the unity of the person, that he was unable to concede any possibility of immortality.

It is only with Thomas Aquinas in the middle ages that some kind of equilibrium seems to be found.

The anthropological pendulum begins to swing again in modern philosophy. With the discovery of new continents and the development of the natural sciences, there developed a new confidence in the power of human reason.

Philosophers such as Descartes and Hume became preoccupied with consciousness, but found it less possible to deal with what we might call 'the real world'.

Immanuel Kant poses the question "what can we know?" and his answer, rather disturbingly is "not much".

We can only know with any degree of certainty that which can be demonstrated mathematically or logically but we cannot know anything about the world around us.

One logical consequence of this for Kant was that we cannot have any knowledge about God, about human freedom, about morality or about beauty; they called it 'the Enlightenment', but it has always seemed rather depressing to me.

Up to the time of the Enlightenment it was always accepted that faith was compatible with reason. Faith certainly went where reason could not go, but it was not in conflict with reason.

The Enlightenment brought with it a shift of emphasis. God was no longer thought of as the source of meaning and the centre of the universe.

People began to think of themselves as the ones who gave meaning to their own existence. Faith was regarded as something totally divorced from reason. It was no longer regarded as possible to speak "reasonably" about the "ultimate end" or "purpose" of human existence.

Pope John Paul II wrote extensively about the need to repair this rupture between faith and reason. In his encyclical letter Fides et Ratio he writes: "Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth... so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to the fullness of truth about themselves."

Following in that tradition, in Laudato Si Pope Francis argues that "science and religion, with their distinctive approaches to understanding reality, can enter into an intense dialogue fruitful for both".

He devotes an entire chapter of his encyclical on the environment to exploring the wisdom that faith brings to our understanding of the moral responsibility that we share for our "common home".

'Nature' and 'purpose' are constantly presented to us when we read the information leaflets that come with medications and power-tools, to mention just two of the more obvious examples.

We read about the various pharmaceutical elements that make up the tablets that we take, how they work, what they are intended to achieve, and what their possible side effect may be. We are warned specifically that we should only use these medications as prescribed and that we should never use drugs prescribed for someone else. The whole system collapses if we deny the relevance of nature and purpose.

Yet this is precisely what we seem to have done with our own humanity. As Alasdair MacIntyre, the Scottish philosopher, points out, much of contemporary philosophy has denied the existence of a defined human nature and refuses to engage with the idea of an ultimate end towards which our humanity is directed. Yet we still use the language of morality.

"Since the whole point of ethics - both as a theoretical and a practical discipline - is to enable man to pass from his present state to his true end, the elimination of any notion of essential human nature, and with it the abandonment of any notion of telos, the ultimate end, leaves behind a moral scheme whose two remaining elements have a relationship which seems totally unclear," writes MacIntyre in After Virtue, his study of moral theory.

We see the knock-on effects of this in much of the moral argument that goes on at the present time, especially in relation to healthcare ethics and sexual ethics.

Mary Warnock, the British philosopher and writer on existentialism, argues that what an embryo is has nothing to do with how we ought to treat it.

The status of a human embryo, in her view, is determined by how we feel about it or what it represents for us. It has nothing to do with fact.

Much of the argument in favour of same-sex marriage in the recent referendum and, indeed some of what we are beginning to hear about assisted suicide, is based almost exclusively on feeling.

The feelings are not the problem and, indeed, I think it is fair to say that, where the Church falls short is in its failure to take on board the power of emotion.

The real problem, however, is with the denial of human nature in its integral totality and the rejection of any purpose other than our own.

Of particular interest to us today is the philosophy of Max Scheler, the German philosopher who believed that Kant was mistaken.

He identified four categories of what he called material values. These include all sorts of things which can be sensed or experienced.

The higher orders of values included the beautiful and the ugly, the legal and the illegal, and religious values such as beatitude, despair, holiness and unholiness.

For Scheler, moral goodness is the experience of a person which follows on the decision to realise some material value.

The higher, and the more spiritual the value realised, the greater the moral good. For our purposes - and to cut to the chase - I think the significant thing is that, for Scheler, personal goodness or morality is a feeling or an experience, rather than any actual change in the person.

Karol Wojtyla, better known as Pope John Paul II, was an accomplished philosopher and author long before he became Pope.

He took a particular interest in the writings of Scheler and he greatly appreciated Scheler's focus on the emotional energy of the human person.

Like most of us, he understood that emotional responses can often be the essential energy behind personal actions and commitments.

He argued, however, that goodness is objective; it is inherent in the very nature of things.

For him, moral goodness is rooted in decision and action rather than simply in feelings. We act morally when we decide to realise an objective good.

One of the best expressions of this point of view is his statement: "Solidarity is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far.

"On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say, to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all."

Pope Francis points out that those who reject the Church's insistence on objective moral norms as absolutist are often quite absolutist themselves, especially when it comes to proclaiming the rights of individuals.

By contrast he argues: "In the absence of objective truths or sound principles other than the satisfaction of our own desires and immediate needs, what limits can be placed on human trafficking, organised crime, the drug trade, commerce in blood diamonds and the fur of endangered species?

"Is it not the same relativistic logic which justifies buying the organs of the poor for resale or use in experimentation, or eliminating children because they are not what their parents wanted?"

What people find attractive, I think, is the fact that behind the often very challenging teaching of Francis, there is a very real humanity.

As a Jesuit, Francis would have been trained in what we call spiritual accompaniment. Speaking of this he says: "One who accompanies others has to realise that each person's situation before God and their life in grace are mysteries which no one can fully know from without.

"The Gospel tells us to correct others and to help them to grow on the basis of a recognition of the objective evil of their actions, but without making judgments about their responsibility and culpability."

He affirms the real distinction between good and evil, but he also acknowledges the struggles that people face in their daily lives.

When Jorge Bergoglio was elected Pope, I went looking to see what he had written.

All I could find was a book called On Heaven and Earth. It is not really a book at all, but a series of conversations between the then Archbishop of Buenos Aires and a Jewish Rabbi named Abraham Skorka, who was his friend.

Looking back now, I think these conversations tell us something very important about Pope Francis.

He knows what he believes, but he also wants to understand what other people believe. He seems to recognise that his own faith can be enriched rather than diminished through dialogue.

I think it was this same humble confidence that inspired Pope Francis to invite the whole Catholic world to reflect on the challenges facing the family and to send him the results of their reflections.

This was not a sociological analysis - it was an invitation to evangelical discernment. It was not about changing the objective truth, or indeed because Francis had no ideas of his own.

I think he was simply acknowledging that, even if the Pope is guided by the Holy Spirit in matters of faith and morals, he does not have a monopoly on wisdom and truth.

In this, he was not only modelling a new style of leadership but he was asking the lay faithful to exercise the responsibilities of their Baptism.

As far as Pope Francis is concerned, it is the "love of God" that makes sense of the Church's moral teaching.

Without it, all we are left with is "the disjointed transmission of a multitude of doctrines".

It is clear that, for Francis, morality is not just about the avoidance of sin. Morality at its best is a relationship.

Through a personal encounter with the love of God, we are motivated to become what Pope Francis calls "missionary disciples".

For many of us the word "missionary" tends to be associated with somewhere foreign, while the word disciple suggests a bygone age.

But Francis is talking about here and now. He is talking about our being filled with a desire to share with others in a very practical way the love that we ourselves have experienced.

:: Dr Kevin Doran is the Bishop of Elphin. This is abridged from an address called 'Pope Francis: Sociological Analysis or Evangelical Discernment' which he gave at the Percy French Summer School at Castlecoote, Co Roscommon in July.