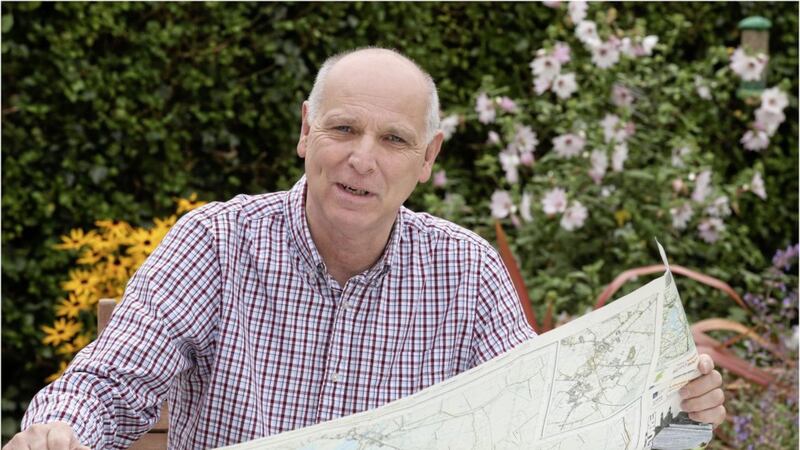

IT BEGAN with what at first I thought were harmless headaches but which turned out to be the symptoms of a brain tumour. At the time I was working on my latest Irish travel book, Shannon Country, which required considerable driving, cycling, walking, researching and writing, so a few paracetamols helped with the pain.

However, the headaches continued in an intermittent fashion for several weeks. I arranged a visit to my GP in Belfast who asked me to describe the symptoms on a scale of one to 10. I rated the headaches as a five although they were difficult to quantify and describe accurately.

While waiting for an appointment with a consultant, I developed a wobble in my walking which triggered alarm bells and I returned to my doctor who organised an urgent private MRI scan for the following morning. This revealed a blockage at the base of my skull and I was immediately referred and admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital. It was a step into the unknown.

More scans and tests revealed a growth on my brain, known in medical terminology as a haemangioblastoma, a rare tumour formed of a mass of blood vessels. This type of tumour is normally benign and can usually be removed by surgery, but the frightening reality was that it would prove fatal if left untreated.

The suddenness of this, a sense of helplessness and loss of control unnerved me, but I concentrated on what the surgeons were saying and events moved quickly. They confirmed they would operate within a few days and I was astonished at the speed of the turnaround. There was no time to agonise or reflect on the fragility of life.

The registrar showed me the brain scan, pointing out the delicate surgical work and intricacies involved. Surgery is never without risk due to possible complications but I knew I had to put my faith in the medical staff as I had no other option. A seven-hour operation followed, during which the whole tumour was successfully and skilfully removed.

It is worth quoting from the painfully honest book Do No Harm by the English neurosurgeon Henry Marsh (which I read after my hospital stay). He wrote about this particular type of tumour: "There is a small risk of disaster with surgery, since the mass of blood vessels can cause catastrophic haemorrhage if you do not handle the tumour correctly, but there is a much greater chance of success. This is the kind of operation that neurosurgeons love – a technical challenge with a profoundly grateful patient at the end of it if all goes well."

Never a truer word was written about the profoundness of my and my family’s gratitude. It made me aware that most of us are ignorant of medical science, especially in working with such precision on the body’s most complicated organ.

During my two weeks in hospital I banished negativity, taking consolation in poetry, especially the work of Dubliner Paul Durcan, the Scottish poet of landscape Norman MacCaig and the Liverpudlian Roger McGough – all of whom cheered me up with their humour, although there is also a darker side to their writing.

I have always loved the McGough poem Bits of Me: When people ask: ‘How are you?’/ I say, ‘Bits of me are fine.’/And they are. Lots of me I’d take/ anywhere. Be proud to show off.

This resonated deeply with me in recovery and over the next week surrounded by a battery of monitors, machines, tubes and wires. In a hospital stay you appreciate the professionalism of everyone, from nurses to neurosurgeons, porters, cleaners, cooks and orderlies to the juggling job of the bed-manager and ward sister.

The small army of surgeons, consultants, doctors, anaesthetists and radiologists carry out Trojan work with a compassion of which they should be rightly proud. Their energy, persistence and goodwill to ensure patients receive the best care is remarkable.

After returning home, two stones lighter and very frail, it was a slow journey to rebuild my strength with the help of after-care staff. Could there be any other social care system in the world where so much support is afforded to a patient? Everyone is aware that the NHS is not a perfect system and its underfunding and lack of resources mean it faces intense pressure as well as being undervalued.

Like many people in my street, I did not miss a single Thursday night applauding the NHS during the early period of lockdown this year.

People who come through a serious operation often see it as a wake-up call, and while there is no doubting this, it also brings life into sharper focus. I returned to my work to complete the writing of my book on the River Shannon while the final editing, revising, fact-checking and proofreading was carried out during lockdown. On my Shannon travels I had come to know the river with every shift of the seasons and the book is in part a compendium of stories from people I met and befriended.

Prior to becoming a self-isolating, full-time writer, I was a journalist for half a lifetime, covering the Troubles, dodging bullets and petrol bombs in riots, seeing death at first hand on the streets of Derry, and the awful tragedy of the loss of so many lives. In a strange way, by coming through this life-changing event, I feel I have dodged another bullet, and each day is a day to value.

Half the people who live with pain ignore it and the numbers suffering from headache disorders or migraine is rising. I hope this article increases awareness of the dangers of disregarding any new symptoms and encourages a visit to the doctor.

As someone who has written about the natural world, and what are known as ‘encounters of meaning’, the post-op period made me even more aware of the magic of the ordinary.

Frequently I have thought about how grateful I am to have been given, as it were, ‘a second chance’, and to have that exhilarating feeling of being reborn since there are many things I still want to do. This has helped me focus on the innocuous but special moments of small wonder: logs crackling in a fire, cinnamon-scented coffee, the artistry of spider webs in a hedge, and the fresh smell of the air after rain.

The material things in life are much less important than many sometimes think and coming safely through this has given me a new capacity for celebrating love and life.

Dark humour can be a coping mechanism for dealing with traumatic events over which you have no control. My hospital ward companions delighted in exchanging ‘organ recitals’ about their medical history, recounting amusing tales with dry jokes to inject some ‘humour with our tumour’.

This reminds me of a quotation from the writer Gabriel García Márquez who once said, "We relish life more in the remembrance, than in the actual experience."

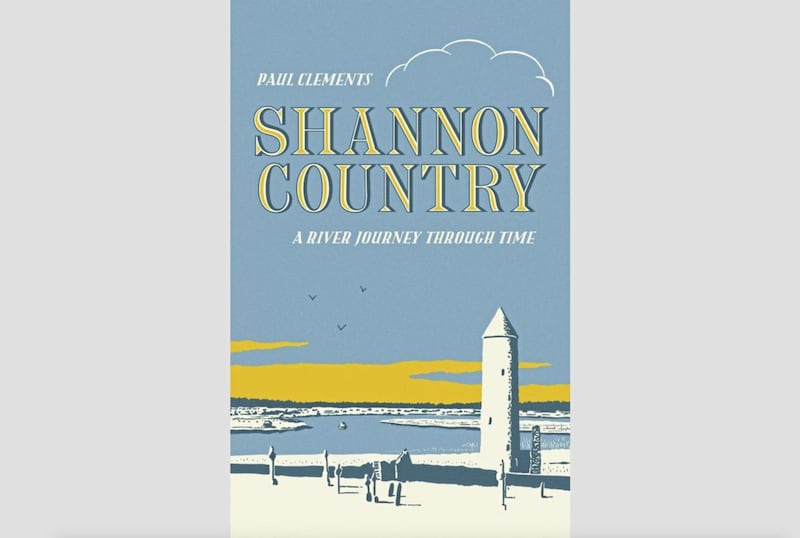

Paul Clements’s new travel book Shannon Country: A River Journey Through Time is published by The Lilliput Press and will be launched online tonight at https://youtu.be/dQVboiwFqFI. A portion of the royalties from the sale of the book will be donated to the charity Brainwaves. It is available from bookshops or directly from lilliputpress.ie