WE ALL remember school days and we usually remember our teachers – for better or worse. Teachers can make or break a child’s education and parents and pupils can be very critical but what of the teacher’s side of the story?

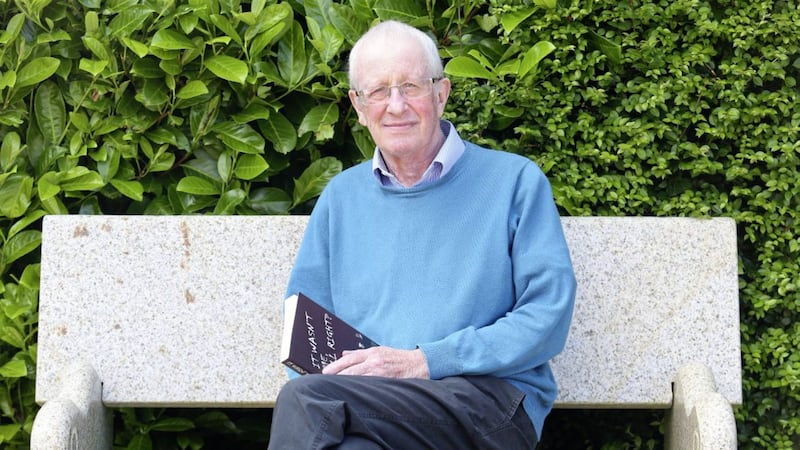

Not often you get their honest opinion and that’s why Robert Rooney’s book It Wasn’t Me, All Right? is such a fascinating look into the classroom and behind the staffroom door.

Although he doesn’t mention St Malachy’s, when he says his school backed on to a prison wall in north Belfast it’s a bit of a give away. As a boy, Robert hated primary school and wasn’t much fussed on secondary either but when it came to being responsible for the education of teenage boys with moderate learning difficulties, he remembered what it is like being a pupil and he determined his boys would enjoy learning and trust him.

He was a good story teller

Even before becoming a teacher, Robert always had a vivid excuse when caught 'mitching’ – being absent without leave was just another challenge.

One exceptional excuse was that he’d been stuck in the toilet with a serious bout of diarrhoea. He got his mother to write a letter confirming her full permission for her son missing class but not mentioning why. Her son then declined to discuss the situation with inquisitive teaching staff as, he said, it was a much too personal issue. He got away with it!

His teaching credentials were second to none, his parents, grandfather and uncle all in education. He followed suit.

Three weeks into his teaching career he was confronted by Henry, known as 'Piggy' – these were different times, remember – a powerfully built 6ft-tall 16-year-old screaming abuse and challenging Robert for trying to discipline him after he burst unceremoniously into his classroom with a message.

Things threatened to get out of hand. It was a frightening situation when the pupil took of his belt and wound it around his fist. Eventually he was ejected into the corridor.

“Luckily the shouting had attracted the attention of Piggy's teacher who had materialised beside me. Looking totally unconcerned, he quietly – almost laconically – said: ‘Put your belt back on, Henry. If your trousers fall down you’ll get your death of cold and possibly six months for indecent exposure.’"

He adds: “This teacher had an ability to give [the boys] a sense of worth and dignity. He was the reason I ended up in that school. He was my father.”

And thanks to his father’s example, Robert and Piggy made their peace and respect was achieved.

His father, John Rooney, was his mentor. They fished together, moored their boat in Carrickfergus and in teaching they learned from each other.

The years between 1965 and 69 were happy ones

At 25 he married and life was good.

“I was serving my apprenticeship; I thought teaching must be one of the easiest jobs around.”

That was somewhat naive. The pressures were great, not least with his father being permanently paralysed from the neck down due to a motorway accident involving a drunken driver.

His love for his father and the increasing civil unrest ‘trapped’ him, however; as he watched this friends and colleagues leave for a better life away from Northern Ireland, he dedicated himself to teaching the vulnerable boys at St Aloysius' (called St Cuthbert's in the book), giving them skills to take up employment in later life.

As his story unfolds, Robert’s interaction with the boys is fascinating; a fan of the Goons, he has a fine sense of humour which radiated through the classroom and into the book.

One student, Jono, asks can he learn Irish. Of course that was possible – everyday phrases to start with? No, specifics were needed. Like what?

“‘I was thinking more like Left, right, about turn, quick march, shoulder arms.' Poor Jono later ended up spending eight years in the Maze prison.”

He played darts with the boys, introduced them to music and for every hit parade piece they brought in he played one of his favourites. One hitherto difficult boy began to listen and took some of ‘Sir’s’ discs home.

Fifteen years later Robert was sitting in a bar when a complimentary drink arrived – it was from Pierce. They chatted. “Do you know what I’m doing after I leave here?” Pierce asked his former teacher. “I’m going home to play Beethoven’s Sixth. I’ve dozens of classical music records and I love them thanks to you.” Robert writes: “I felt on top of the world for a good week after that.”

He had a problem

One particular boy continuously muttered obscenities, especially when the principal approached across the school yard.

He would start: “‘What the f*** does be want over here, nosey ba****d. Here he comes now, the big sh**e’, followed by observations referring to human genitalia and repeated suggestion that he was a less than clean, illegitimate son of a loose woman’s melt!”

It was only years later, when the name became known, that Robert became convinced the boy suffered from Tourette’s syndrome.

I mentioned that, in general, he didn’t cover the civil unrest during those years.

“There are plenty of books on the Troubles; my focus for the boys was to provide an oasis away from poverty and fighting, a place where they could learn, feeling safe and valued," Robert says.

"Too many teachers come from middle-class families where there is little appreciation of how difficult life can be for their more unfortunate neighbours. A combination of ignorance and snobbery provides a lack of insight and respect.”

This book was written almost five years ago but, because of illness, only published now.

“I have eight grandchildren and, for them and others, I wanted to leave a lasting and truthful record,” he says.

That he has done in fine style.

RECORDS show that September 10 – tomorrow – is a fine, rain free day. I’ve been monitoring this for over 30 years and apart from some drizzle last year, the day has been good. Let’s see!